[title]

If you’re ever feeling lonely, go to a museum and read the words on the walls. Someone will always keep you company by standing directly in front of you.

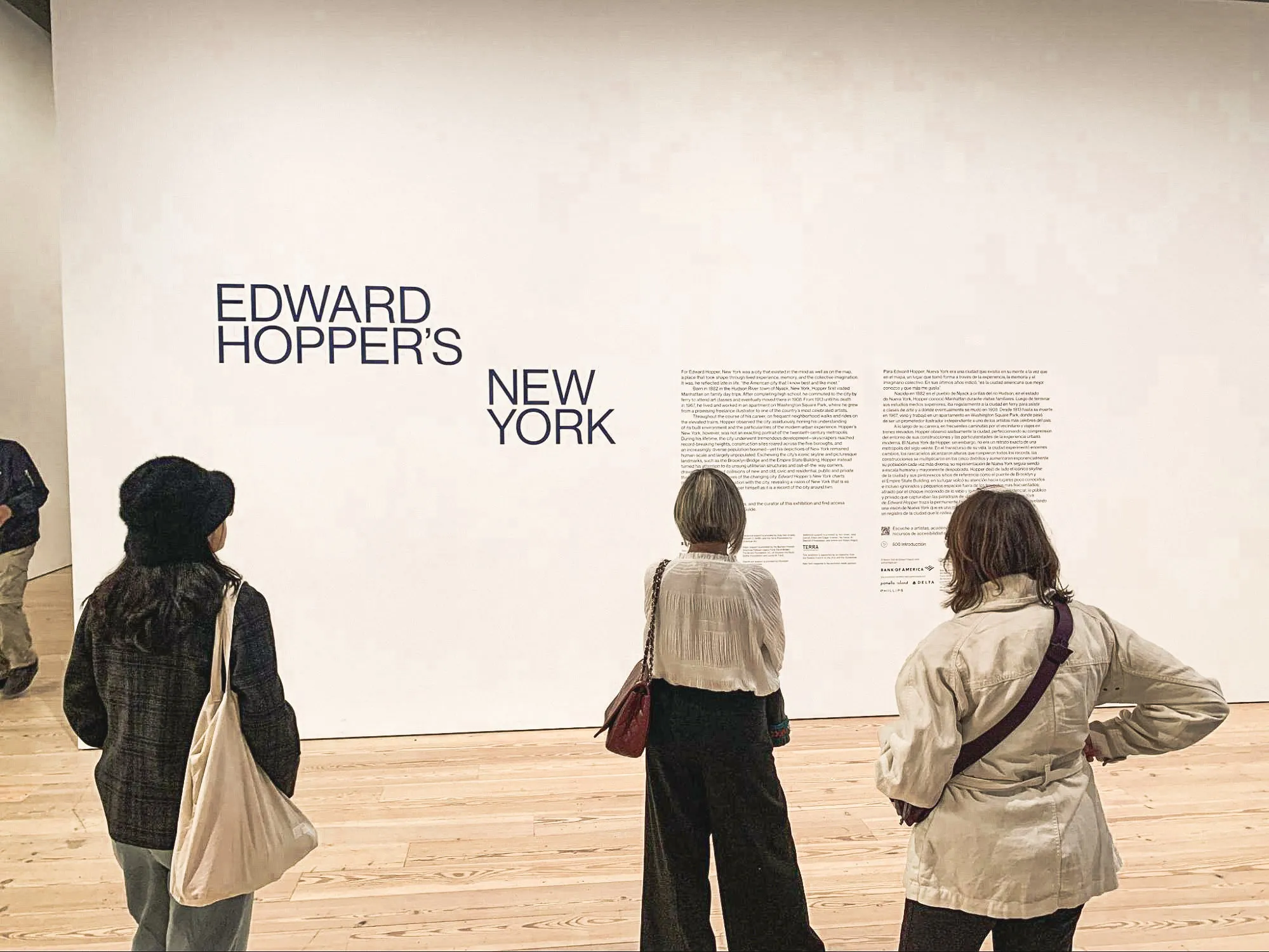

“Let the gentle people out. Let the gentle people out,” a museum guard by the elevator instructed. The fifth floor of the Whitney Museum was a bit too full: a gaggle of school groups, solo adventurers, old couples, odd couples, Old Money in suits and furs, and tourists dressed in near-tactical gear to battle the city’s streets.

“It hasn’t been like this since Warhol,” my friend who works there told me.

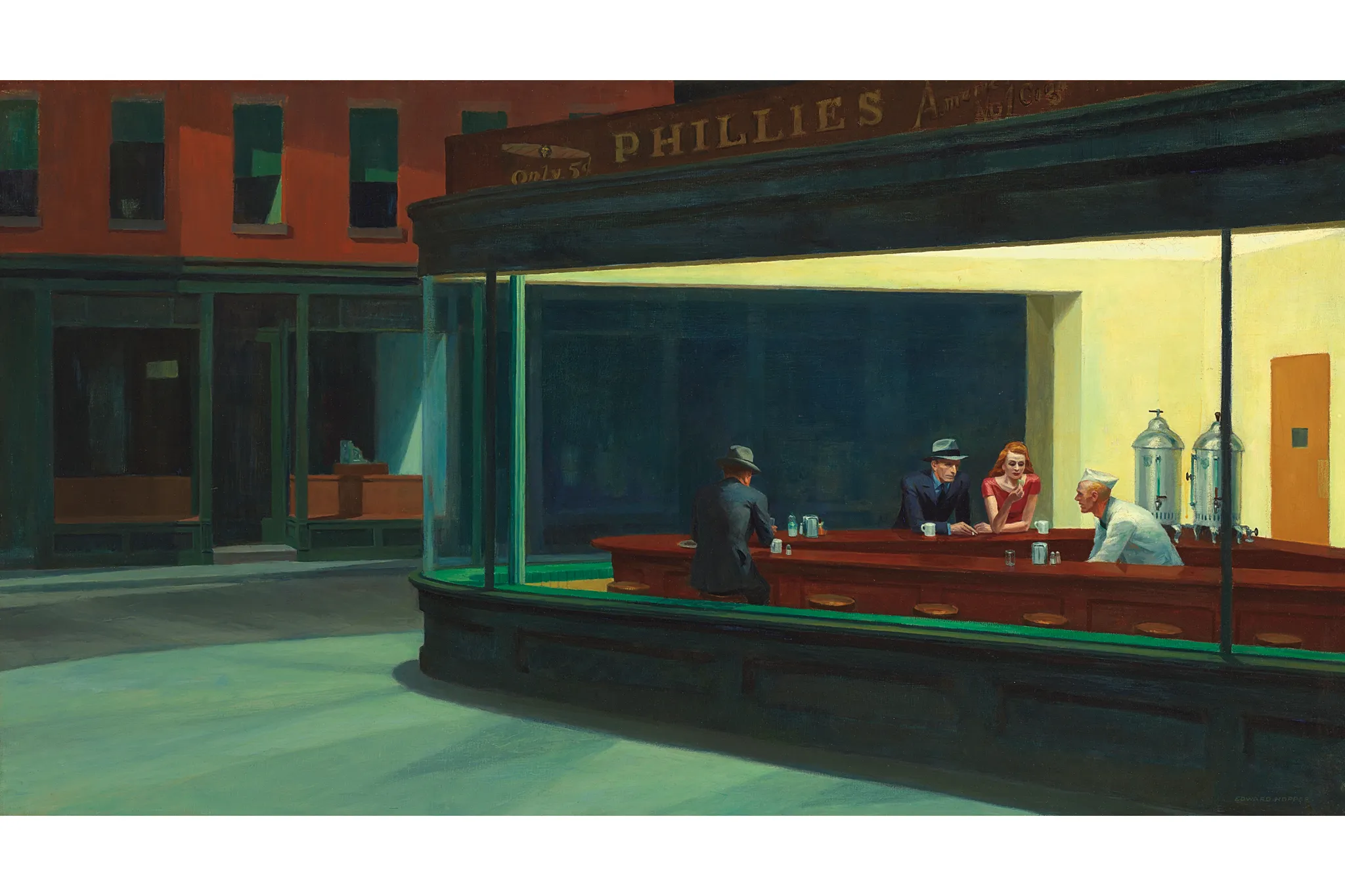

Edward Hopper is not Andy Warhol. The mass-produced, glitzy, pop glam of sweaty Studio 54 is at odds with the hand-painted, muted melancholy of an eerily empty New York. So what was drawing people in equal numbers to crowd together to see the lonely people in “Edward Hopper’s New York?” Support for a homegrown boy, who lived down the block for 50 years? Lusting after a version of the city with fewer people? Something about the pandemic (a viral tweet said “we are all edward hopper paintings now”)? Or maybe we all know that one painting of his, the one of a diner.

I was there as part of my quest to fall back in love with New York by becoming a tourist. Tourists love museums, second only to taking photos of themselves in museums, and The Whitney is one of my favorites. Thanks to the institution’s generous definition of the word “artist,” I’ve been a member at a discounted rate for years now. I was curious if this new exhibit about a New Yorker making art about New York could re-spark my devotion to the city I also call home. After some more death-defying tourist attractions, I wanted something less scary, and the only deaths that happen in museums are to egos.

I joined the free 1pm tour a few minutes late with 20 other frugal bastards and couldn’t hear a damn thing. The soft-spoken are well-suited for many careers–librarians, assassins– but a microphone-less guide in an overcrowded exhibit isn’t at the top of the list. Everyone else was politely nodding along, so I assume they had received an invisible earpiece, gained supersonic hearing by being bitten by a bat, or were pretending to hear.

Without warning, we moved quickly, like a school of fish navigating a sea crowded with sharks and coral. In the transition, I politely jockeyed to land in a position closer to our guide. At a painting of a woman in a droopy hat sitting alone in a diner with a cup of coffee, I heard the guide ask, “Is she waiting for someone? Did someone leave?” At another piece shortly after of a woman sitting in her bed, facing a window, emotionless, I heard, “Is she enjoying the sun? Does she want to get out? It all becomes ambiguous about what they’re feeling.”

The women’s expressions didn’t seem that ambiguous to me; the people in these paintings were clearly sad, one poorly-guarded balcony away from meeting their Maker (Hopper). But perhaps I was projecting my own melancholy.

We pulled into our next destination: “Approaching a City,” a painting of a tunnel.

“Hopper is really trying to capture what he thought of as the thrill, the anxiety, the excitement of entering a major city where you’re taking in everything around you but also looking ahead to this unknown, this dark tunnel ahead,” said an exhibit curator in a YouTube video I watched later at home where I could hear. I’ve felt this companion excitement-and-fear the city stirs many times before. In the spirit of a tourist, I snapped a smiling selfie in front of the sad work. The great artists of the past would be delighted to learn their time-intensive masterworks have become backdrops for self-portraits made in a millisecond.

We continued our tour and I realized Hopper really liked buildings. When asked, “What makes a city a city?” most would wax poetic about how it’s not buildings, it’s people. Hopper seems to say, “Well yeah, but it’s a lot of buildings, too.” His obsession with infrastructure—homes, businesses, bridges, storefronts, smokestacks—would make you think he was running for office. (He did campaign at to save his Washington Square Park apartment/studio from an NYU takeover.)

But his paintings of cityscapes aren’t literal, I learned. They’re remembered, imagined, a composite of places he experienced. It’s New York from memory, what one mind chose to focus on in a city with a billion things to choose from. As our guide whispered later in the tour, quoting Hopper: “I don’t think I ever tried to paint the American scene; I’m trying to paint myself.”

I tried to keep up with our guide, who vanished into the next room—an area of the exhibit called “The Horizontal City,” where five of Hopper’s larger works were laid out, scenes of an unpopulated town celebrating lower levels. Like a Venetian who hates canals, an Amsterdammer who hates weed, or a Parisian who hates feeling superior to others, Hopper the New Yorker hated skyscrapers. Living and painting during the 1930s “race to the sky,” when the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building grew taller than any building had before, Hopper was strictly anti-vertical growth. At 6-foot-5, Hopper may have feared the competition. Or was afraid his characters would jump. So he painted his version of the city, sticking to eye-level, human scale, bucking the city growing upward.

“Through their front windows, the Hoppers witnessed the incessant cycles of demolition and construction as 19th-century buildings like their own were torn down to make way for new structures,” said The Guide (a composite character I’ve created in the spirit of Hopper from the museum labels, the curator on YouTube, and the churchmouse in person, because I don’t remember who said it). You can live in a place and dislike parts of it, Hopper reminded me, and even press against parts of it.

Maybe Hopper hated skyscrapers because he couldn’t peer inside.

“In city life, no matter where you live, when it’s nighttime and it’s dark outside and your interior lights are on, the interior becomes like a theatre and you have these moments of incidental voyeurism,” said the curator online. I heard our guide in the museum say “voyeurism,” too. “I was just going to say that: this is voyeurism,” someone on the tour said to their friend. Sure you were, lady.

Hopper often tried to capture the interior and exterior of buildings, which he called a “common visual sensation,” in a painting. His body of work suggests that while we can see inside and outside buildings at the same time, we can only see the exterior of people. The thought crosses my mind that maybe these people aren’t sad, they’re just alone. Away from the gaze of others, they’re not performing their joy, but perhaps feeling peace, reflection, calm by being alone. The paintings don’t scream; like a librarian or assassin, they’re whispering.

Hopper didn’t experience and capture the city alone; a figure present in his life and paintings is his wife and fellow artist Josephine Veerstille Hopper, highlighted in the exhibit. She modeled for every one of his paintings, less out of affection and more frugality, and paused her career to support his.

“She was very devoted to him, very supportive of him. He was maybe not so supportive, but he was grateful,” our guide told us. The exhibit featured several of her works, a celebration of the team effort that is art making and what might have been had the focus been shifted elsewhere. This biographical background adds brushstrokes to the stories we might craft about the lonely, longing women in Hopper’s work.

“I always think of New York as a palimpsest—histories built upon histories,” said the curator in the YouTube video. After googling what a palimpsest is, I agree. Not only histories upon histories, but imaginings on imaginings. “Edward Hopper’s New York” means there are millions on millions of “[Your Name Here]’s New Yorks.”

One end of the exhibit has floor-to-ceiling windows that look out over the West Village. It might be why the Whitney is my favorite museum: you get art and a view. This layout of the exhibit was intentional, folding Hopper’s subject into the exhibit. I looked through the window. There, trees were turning colors for fall, there’s a building in the distance a bit taller than Hopper would have liked, a huge billboard besting the smaller, local pharmacies and diners he painted. Down below, people moving and milling, shifting, talking, behind me are tourists and locals chatting and smiling, outside are school groups and old couples having lunch, interacting, laughing. It feels closer to Zach Zimmerman’s New York.

A guard on the elevator announced it was going down. “Where’s everybody going? Home? Must be nice.”

Did Hopper love his home?

“New York is the American city that I know best and like most,” he once said, which might be the closest a New Yorker can get to love.

Before I headed home, I realized I hadn’t seen the diner one. You’d know it if you saw it: a painting of a view from outside a windowed diner, with an employee, two men in suits, and a woman in a red dress; “Nighthawks” I learned is the name. Turns out the Art Institute of Chicago wouldn’t give it up. Hopper’s best-known work, which towers over his others like a skyscraper, is just out of focus of this exhibit. I think he’d like that. To see that painting of maybe-lonely people in New York, you’ll have to go to Chicago.

Zach Zimmerman is a queer comedian, writer, and author of Time Out New York’s “Pretend I’m A Tourist” column. A regular at the Comedy Cellar, Zach has appeared on The Late Late Show with James Corden and had a debut album “Clean Comedy” debut on the Billboard Top 10. Zach’s writing has been published in The New Yorker, McSweeney’s, and The Washington Post; and Zach’s first book Is It Hot in Here? (Or Am I Suffering for All Eternity for the Sins I Committed on Earth?) (April 2023) is available for pre-order now.