[title]

The Gershwin Theatre was all grand and all green: bedazzled blazers, witches’ hats, extravagant black gowns and intricate all-green face paint. There was an actual, former Elphaba (out of costume) posted up at the branded step-and-repeat with the catchphrase “Everyone deserves the chance to fly.”

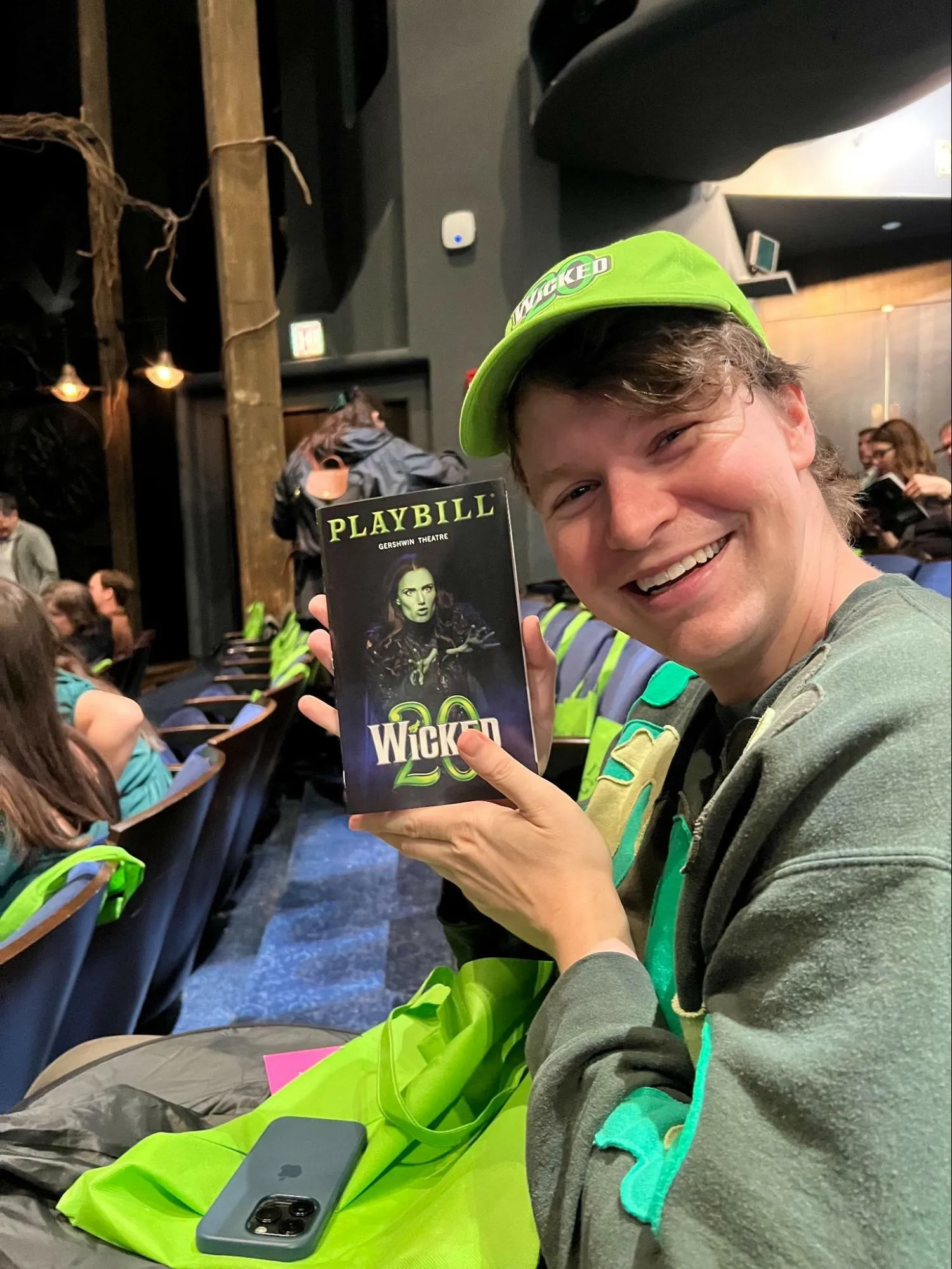

It was the 20th anniversary “Green” performance of Wicked on Wicked Day, a holiday unobserved by our federal government, celebrating 20 years on Broadway (a feat only ever accomplished by three other musicals: Phantom of the Opera, Chicago, and The Lion King). I chose the “Green” show over the “Pink” matinee due to scheduling, not out of any allegiance to Elphaba (though, upon reflecting, I am probably an Elphaba, Glinda rising: a stubborn, introverted nerd, with shades of a bratty, spotlight-craving diva.) Green-themed playbills with an action shot of Idina Menzel on the cover were distributed (the pink matinee had Kristen Chenoweth, the original Glinda), and green swag bags were waiting at our seats (pins, mascara, and a ghost-shaped Reese’s, oh my!). There was festivity in the theatre, a buzz in the room, anticipation, excitement. Five former Elphabas came on stage to introduce the show to an audience full of people I’m certain had already seen the show at least twice before.

“I first saw it in fifth grade, we learned the music and everything” my date Ali told me. Don’t tell her, but she was the 14th person I asked. The declines came with a variety of excuses: booked, out of town, too cool, and my favorite, someone who already had plans to see Wicked twice this year. Wicked was my first Broadway show, so it holds a special, potent place in my heart. It’s important for your first viewing of Wicked to be as a kid so nostalgia can fill in any of the cracks and valleys that age and cynicism carve.

My high school theatre teacher Mr. V. (called that not to protect his identity, but because that’s what we called him) had a habit of adding lines and characters to published plays. In One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, he didn’t like that the stuttering Billy Bibbit slept with a sex worker, so he invented Nancy Nesbit, a young lady who also had a stutter. Billy and Nancy only ever kiss, though Billy still offs himself afterward. It must have been some kiss. Mr. V. brought that same ambitious, entrepreneurial spirit to the annual trips he helped organize to New York City. What my public high school lacked in funding, they made up for with three incredible art teachers: Mr. V (theater), Mr. Deck (visual arts) and Mrs. Deck (dance). Every year, they took 40 teenagers on an overnight bus trip from Roanoke, Virginia to New York City. We raised money for the trip and raised hell for the teachers who led us on a mad-dash New York on a budget experience.

I’d only left Virginia for a beach or amusement park, so this first Big City Experience was significant. When the bus emerged from the Lincoln Tunnel into Manhattan, I looked up at buildings taller than any I’d ever seen before. We snaked through the grid on our way to the Hotel Wellington at the corner of 55th and 7th, where we stayed four to a room at a height I’d never slept at before. The view outside the window of another building’s brick, concrete below, felt like the set of a play. The tall elevators down took hours, but I didn’t care: I was 15 and excited to be in New York.

The point of the annual trips was to expose us to the arts: museums, Broadway shows, and one interactive dinner. One year was Mars 2112, where aliens served your entrees, another year was the Jekyll & Hyde Club, where puppets on the wall and actors interact with diners (whatever actor was playing the rhinoceros was especially cheeky). A theater nerd myself, I was particularly interested in what shows we’d see, and which would be my very first Broadway show. I never took a class with Mr. Deck, opting for the performing arts rather than visual ones, but I found myself with him one day and asked if he knew what shows we were going to see. He told me he’d gotten us a group rate to a show still in previews: a new musical about the witches of Oz.

We sat in the nosebleeds, 40 of us, as we were among the first to witness the “untold” story of the witches of Oz. I heard voices I’d never heard (Idina and Kristin) and saw special effects I’d never seen. It all built to “Defying Gravity,” when our Wicked Witch of the West takes flight, ascending center-stage in the show-stopping, spell-binding, act one-ending number. The quick blackout after it left me feeling jaw-dropped, stunned, in awe.

Blue Man Group was the show we saw the following night. I felt bad for the boys in blue, the lady in green had already won me over.

When the flying monkeys entered to crank the wheel to lift the map of Oz into its 21st year, the audience applauded. When each main cast member entered, we clapped. Sixty-five million tourists and locals will tell you Wicked is a great show; but at the 20th anniversary, we were also a great audience. The show never became a sing-a-long, but it was certainly an applause-break-a-long. We clapped when: Elphaba got her cape, the “There’s no place like home” callback, and, most notably, a quadruple applause break when Galinda changed her name to Glinda. I think the stopwatches at Cannes got jealous.

Admittedly, we were a self-selecting bunch—people who checked our cynicism long before reaching Munchkinland and were returning to a place we’d all experienced before. There was something special in the room.

When the lights snapped back on after the final note of “Defying Gravity,” the young lady next to me— in a green lace dress—was hyperventilating. She was right.

To return to something you’ve already experienced can be a devil’s bargain. I loved Wicked when I first saw it, I loved New York before I lived here, but would revisiting it rekindle something or remind me of something I’ve lost? A revisit can pervert the memory. If you go looking for the same emotion, you’ll likely be disappointed: you never forget your first, and you can’t really compete with it. In that way, you feel a bit numb returning to the scene of your transformation. But it is a way to take stock of yourself —to measure your growth (or decline) against a measuring stick, to see how much you’ve changed in the time since you last visited the thing.

The 20th-anniversary performance was electric and left me with a certain buzz, but it was a year prior when Wicked really felt like it taught me something.

My fourth visit to Wicked (I watch what I like) was my first Broadway show after the pandemic. Masks were still required in the audience, which made things feel muted but made lip-syncing with reckless abandon possible. It was also my first Broadway show high (everyone deserves the chance to fly). Blame it on the weed, but I felt what good acting is during that show: possibility in the face of inevitability. I knew the story by heart, so when a performer said a line, I could truly if the outcome of the moment felt pre-determined or as if anything was possible.

But the headline of this viewing, something I didn’t realize before, was that Elphaba and Glinda are just kids. These towering figures from my childhood, larger-than-life characters that fill the theatre, are just two kids in school, two kids at a dance, two kids bullying and being bullied. And I was no longer a kid. They’d stayed the same age during my viewings over two decades, but I’d matured.

I’m 35 now—a number that feels too large to type. Your body changes over time, but it’s what’s around you that seems to change the most: the train is suddenly full of groups of kids that are younger than you, and those kids aren’t in middle school, they’re in college, then they’re 21 and 25 and when did they start letting kids into bars? And when the hell did Elphaba and Glinda become kids? And I guess I was a kid back then, too. You look back and realize the adult you thought you were wasn’t. You were just a kid.

I closed my eyes just right during “Defying Gravity,” and I felt like maybe I was sending something back—a wish, an energy, a thought—to a kid who sat in the nosebleeds, audience right, last row, two decades prior. My consciousness felt like it could fly back on the notes being sung to my younger self. Again, I was high.

At the intermission of the 20th anniversary (and my fifth viewing), my body felt like it wanted to weep while I waited in line for the bathroom, but I managed to keep it together. I might still need to let the floodgates open. Some things are magical even when you know they’re going to happen. When the show ended, the audience donned hideous lime green hats we’d been given for a picture with the cast. When we left the theatre, scalpers (or mega-fans) tried to buy our playbills at the door. I asked Ali if she loved New York, and she said, “Of course.” It’s hard not to love New York after you’ve just seen Wicked. I rode the subway with a feeling of electricity and luckiness that I now live only 45 minutes away from this epic story that’s stood the test of time.

A lot of what was in New York during my first visit 20 years ago is gone now. The Hotel Wellington shuttered during the pandemic. Mars 2112 closed, and so too, did Jekyl & Hide. Mr. Deck passed away a few years ago. The longer you live in New York, the greater the hazard of losing things you once loved. Businesses and buildings open and shut down, like spikes and valleys on a heart monitor. But Wicked is still here, my time travel portal, to add to the ever-growing and -erasing palimpsest that is my love letter to New York.

Every time I see Elphaba soar, my mind goes back to the 15-year-old kid in the last row, audience right, mezzanine, and I give them a little extra love. I wouldn’t be able to do that without Mr. V who opened up a world to me. It’s so important to show things to young people not just so they can see themselves or what futures might exist for them, but so they have yardsticks to measure themselves against in the future. A lack of art leaves they’re being twice robbed: of experiences, and of nostalgia from those experiences. If Mr. V. hadn’t taken me to New York, I’d never have dreamed of living here, I’d never have made it happen and moved here, I’d never have fallen out of love with New York, I’d never have tried to fall back in love with New York, I’d never have gone to Wicked for the fifth time, I’d never have seen the girl hyperventilating next to me, I’d never have felt nostalgic. And each time my mind flies back to the younger me, across those years, I know how important it is for everyone to see things, to see possibility (even in the face of the inevitable), and to revisit things, to return, to fly back in time to see how you’ve changed, grown, and stayed the same. Because everyone deserves the chance to fly.

Zach Zimmerman is a queer comedian, writer, and author of Time Out New York’s “Pretend I’m A Tourist” column. A regular at the Comedy Cellar, Zach has appeared on The Late Late Show with James Corden and had a debut album “Clean Comedy” debut on the Billboard Top 10. Zach’s writing has been published in The New Yorker, McSweeney’s, and The Washington Post; and Zach’s first book Is It Hot in Here? (Or Am I Suffering for All Eternity for the Sins I Committed on Earth?) is out now.