[title]

“Let Me Tell You” is a series of columns from our expert editors about NYC living, including the best things to do, where to eat and drink, and what to see at the theater. They publish each Tuesday so you’re hearing from us each week. Last time, Senior National News Editor Anna Rahmanan told us about all the cool things to do with kids in NYC this winter.

Reporting on the new Anne Frank exhibition at the Center for Jewish History in Manhattan as a Jewish female journalist just two days after Hamas released three of 90+ Jewish hostages feels daunting. And yet, here I am. After months of anticipatory emails, “Anne Frank: The Exhibition” officially held its preview today ahead of its January 27 opening on International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

One of the most visited historical sites in Europe, the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam is moving to New York for the first time ever. Starting next week, New Yorkers will have the opportunity to walk through a full-scale recreation of the rooms where Anne Frank, her parents Otto and Edith, her sister Margot, the Van Pels family and Fritz Pfeffer (all Jews) spent two years in hiding to avoid Nazi capture. The exhibition also includes a gallery space that walks visitors through the events leading up to the Holocaust, when 6 million Jews were murdered, and its aftermath. Expect to see objects—some original, others exact replicas from the house in Amsterdam—alongside striking images that tell a story Jews can never forget, and are, in fact, called upon to remember to ensure it never happens again.

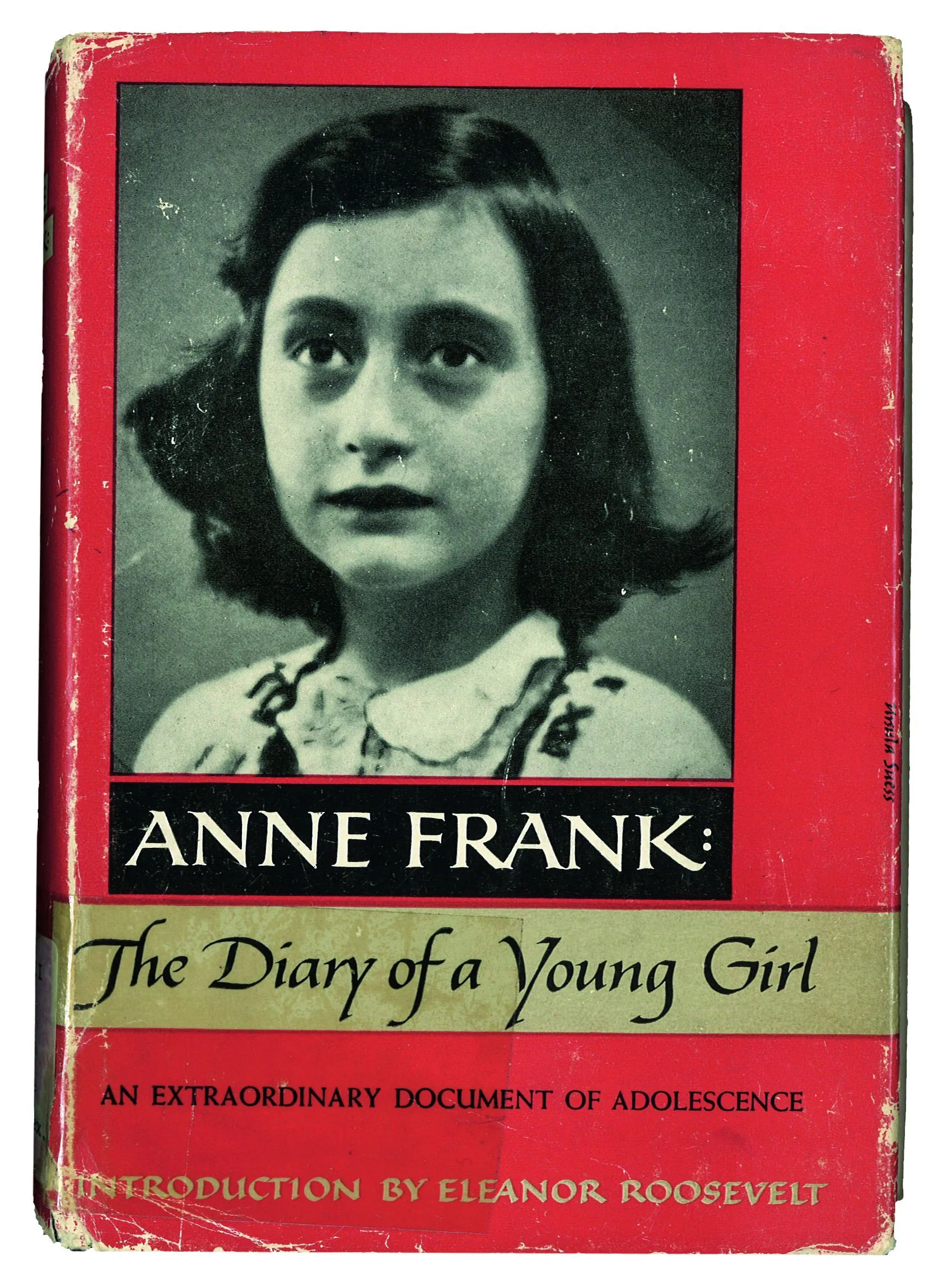

Let’s take a step back: Anne Frank’s diary is a firsthand account of a Jewish girl’s life in hiding during the Nazi occupation. Her father, Otto Frank, was the only member of the family to survive the Holocaust. He was given Anne's diaries and, determined to honor her memory, decided to share them with the world. The 1947 publication of The Diary of a Young Girl eventually turned the annex in Amsterdam, which still stands as it did when the Frank family was captured in 1944, into a global destination and, now, thanks to this new exhibition, it can also be experienced in America.

A few tips: upon entering, be sure to grab one of the available audio guides. The space is filled with artifacts, photos and videos, but the text on the walls is minimal, mostly consisting of quotes from Anne’s diary and from family members. One more thing: brace yourself for a deeply emotional experience.

The exhibition begins with a section titled “Life in Frankfurt before 1929” and moves into the rise of the Nazis, punctuated by poignant quotes.

One of them, by Otto, reads: “As early as 1932, groups of stormtroopers came marching by singing: 'When Jewish blood splatters off the knife.’ … I immediately discussed it with my wife: ‘How can we leave here?’”

As a Jew, witnessing acts of antisemitism in New York and beyond in recent years, leads to a similar question: “how can I live here?”

What’s truly remarkable is the amount of archival footage on display—photos and videos blown up to massive size that demand attention to every detail. In a way, the actual artifacts are less impactful than the images: the clips and photos prove that the people that let the atrocities of the Holocaust happen were real humans that looked just like we do now.

Towards the end of the first section, there is a black-and-white photo of Anne’s kindergarten class. I stare at it, my heart tightening. My firstborn daughter is in kindergarten now.

In the next part of the exhibit, visitors enter a room with three giant screens chronicling the slow but sure destruction of Jewish life in the Netherlands and across Europe. A voiceover explains how the Nazis stripped away Jews’ humanity, starting with the segregation of Jewish students into their own schools, followed by the restriction of where they could deposit their money—money that, in essence, was stolen. As I learned in school and from speaking to Holocaust survivors, the physical killing in the camps was only one part of the horror. The destruction of the human spirit happened long before.

And yet, Anne Frank’s humanity endured. Even while hiding in the cramped annex, at only 13 years old, she still found beauty and hope in the world around her.

“The annex is an ideal place to hide,” reads a quote on display at the entrance of the reproductions of the rooms. “It may be damp and lopsided, but there’s probably not a more comfortable hiding place in all of Amsterdam. No, in all of Holland.”

Then, we enter the annex itself. Every object displayed in glass cases is original—things that Anne, her family and fellow hideout Jews touched and used daily, alongside exact replicas of other items.

There is no air inside the annex reproduction. How could she have lived in such a small, windowless space, never seeing the light of day, I keep wondering. If I can barely breathe in this room, how could Anne have survived in it for so long, alongside others?

The exhibit showcases a handful of spaces: one shared bedroom between Anne and Fritz, a Jewish man of her father’s age; another for her parents and sister Margot; a shared bathroom; a living room and kitchen that the occupants only used at night; and a small room for Peter, another young person who, at one point, Anne found a connection with. In each room, visitors hear voiceovers chronicling part of the Frank family's history, also reading excerpts from Anne’s diary.

“Will I ever be able to write something great?” a voice actress reads from Anne’s diary. The tragic irony is clear: although what she meant by “great” is probably no reflection of what her diary ended up becoming, Anne did change the world through her written word, unknowingly penning a manuscript that would eventually be translated into numerous languages, adapted into films, plays and used as a cornerstone text in Holocaust education. She never got to see it: she died in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1945, likely from typhus, when she was 15 years old. A few weeks later, the camp was liberated.

Like me, you may wish the experience over upon walking out of the reproduced annex, since the space takes your breath away in a horrible, petrifying way. But there is so much more to know and see. Upon entering a separate exhibit area, you'll be surrounded with eerie photos from the camps while a voiceover recalls Otto Frank’s retelling of the day the hiding place was betrayed.

The area floor is marked with a giant map that traces the major ghettos and extermination camps. Walking over it feels like traversing through the blueprint of destruction. I can’t help but wonder: Am I lucky not to have lived through these times, or should I feel sorrow knowing that I, too, would have been murdered if I had?

Above a set of images showing Jews in ghettos, the word “genocide” stands out—a word that carries an even deeper connotation after October 7. For me, the word connects to the 6 million Jews killed during the Holocaust. Today, it is used as an indictment against Jews and Israel. Seeing it alongside proof of destruction in the exhibition, against a people gassed to death for simply being people breaks my heart. The final section of the program focuses on Otto Frank’s survival and his discovery of the deaths of his wife and daughters.

“I don’t know how you do this,” I find myself telling a PR representative in the space.

“I can’t read all of these notes at once,” she responds, pointing to the various letters Otto wrote and his eventual escape.

In a video interview, Miep Gies, Otto's former employee, a Dutch woman who, along with her husband Jan Gies, helped hide the Frank family in their own home, recounts the moment she saw Otto after the Holocaust, when he offered confirmation of his family's passing. Upon hearing the news, she took out Anne's diaries, which she had held onto throughout the years, and handed them to the girl's father, who ultimately published them.

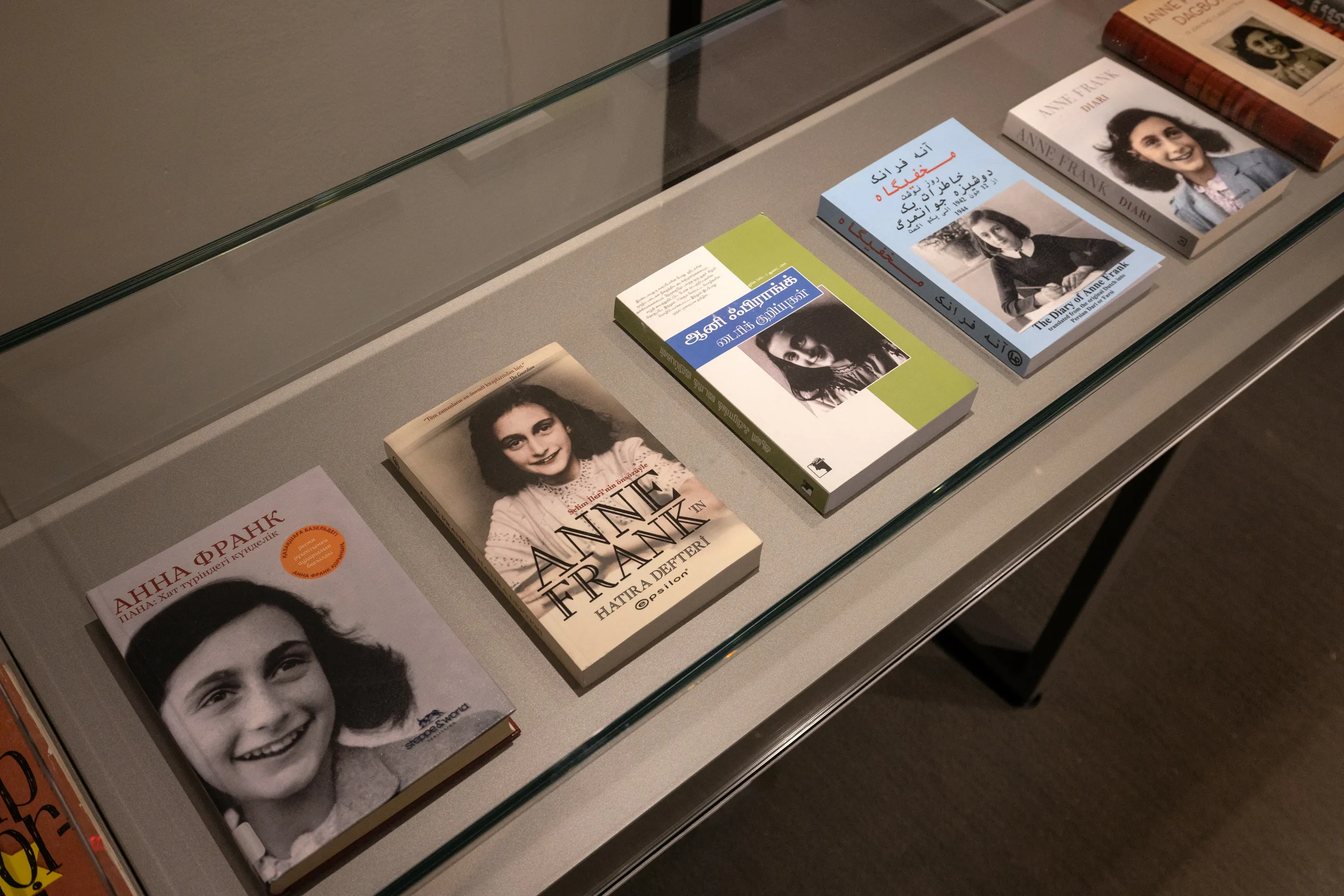

The exhibition ends with a display of all the editions of Anne Frank's diary printed worldwide, alongside posters from plays and films adapted from it—some even award-winning, with one Oscar on display.

“Anne’s diary made you think about the cruel persecution of Jews during the Nazi regime,” a final quote from Otto Frank, dated 1973, reads. “But I want to stress that even now there is a lot of prejudice leading to discrimination in our world, and each of us must fight against it in our own circle.”

Perhaps that is the message I want to stress as well, especially in light of the surge of antisemitic crimes in New York in recent years: let's learn from the past, recognize that discrimination is still part and parcel of our society and let's stand against it.