[title]

If you were alive and clubbing in the boroughs in the 1980s and ‘90s, chances are you saw advertisements for a “sound clash.” If you were lucky—and near enough to Flatbush, Jamaica or Wakefield—you attended these wild, bombastic, occasionally dangerous and ultimately legendary dancehall parties.

Born in Jamaica in the late ‘70s, dancehall found its second home in New York (and, specifically, central Brooklyn) in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Often harder, faster and, later, more digital than its progenitor reggae, dancehall relies on instrumental “riddim” tracks that would be the bedrock for a toaster to sing and talk over. At parties and festivals, dancehall music was blasted over massive sound systems and these “sounds” would battle for supremacy in a clash. Held between competing systems from different cities, boroughs and countries, these sound clashes were the Caribbean equivalent of a rap battle.

“It's hard to explain to somebody if you weren't there,” says DJ, MC and producer Walshy Fire, one half of the Grammy-winning group Major Lazer. “To experience the level of danger, the level of fashion, the flyness. To see people floss at a time where flossing was never a thing, to see floor-to-ceiling, wall-to-wall speakers … Thankfully, we have the flyers."

Birth and death by flyer

Walshy grew up in Kingston’s Half Way Tree neighborhood—home to many legendary dancehall clubs and sounds—and spent years in Miami’s scene and in Connecticut before moving to Canarsie, Brooklyn in 1994. While he was a “very serious cassette seller” from age 14, it was Walshy’s collection of a different kind of ephemera that sparked his newest project: a book titled The Art Of Dancehall.

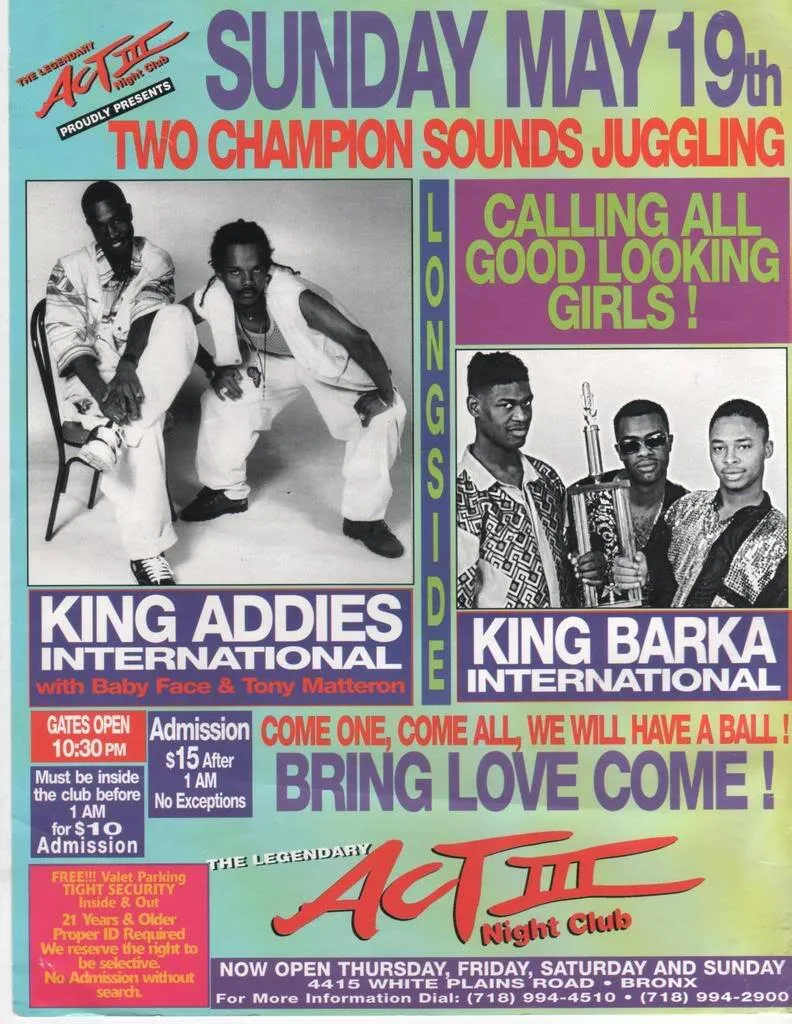

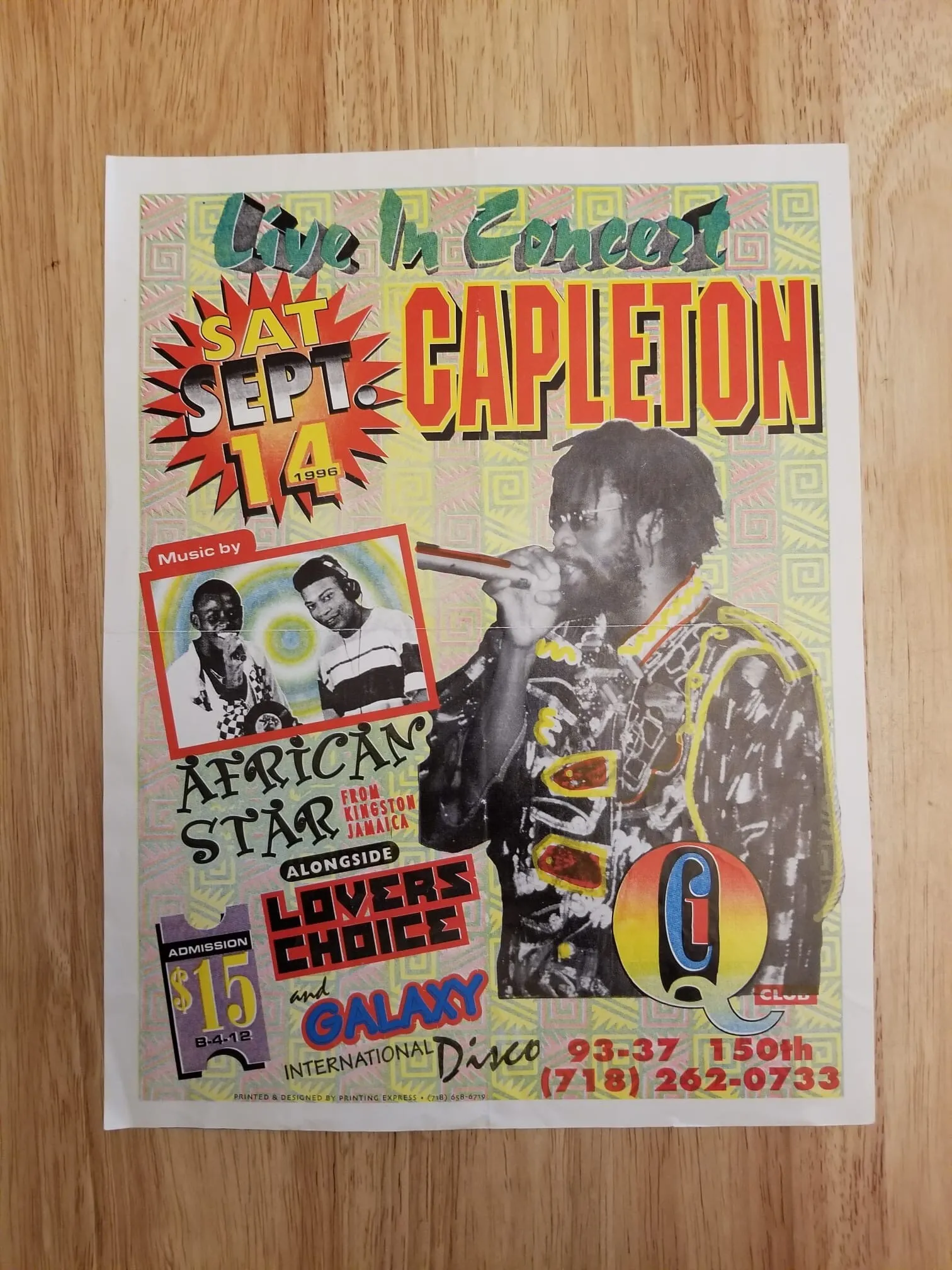

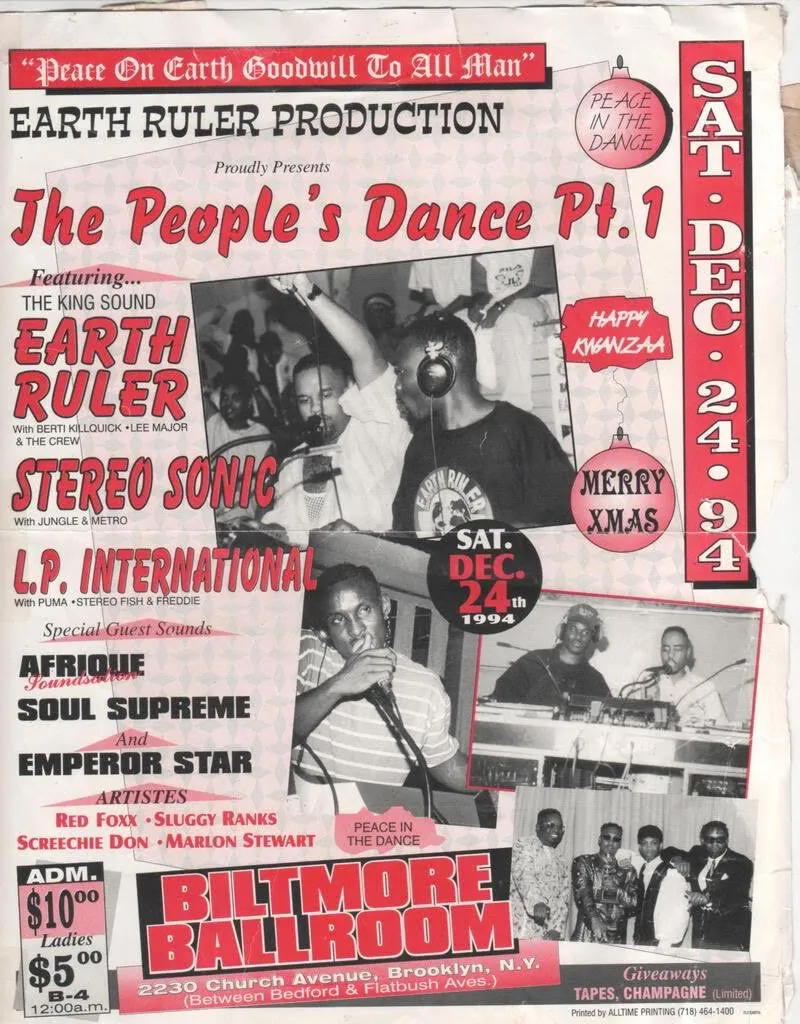

Beginning with his own collection and expanding to that of selectors and soundmen from Jamaica, the U.K., New York and even Japan, the flyers in Art of Dancehall highlight the culture's broad influence. The New York flyers showcase popular local crews like Earth Ruler, LP International and Emperor Hi-Power, who clashed with each other and occasionally, alongside live appearances by Jamaican superstars of the day—including Capleton, Buju Banton, Super Cat, Shaggy and Bounty Killer. The flyers highlight shuttered but not forgotten venues including Flatbush’s Biltmore Ballroom and Tilden Ballroom, Act Three in the Bronx, as well as The Q Club in Jamaica.

“The flyers are always trying to make it look like, if you miss this, you’ll die the next day and you’ll regret in the afterlife,” Walshy says. “A weak flyer meant a weak party, 100 percent. If you didn’t see ‘musical murder’ splashed across the front with a bomb exposure behind it, yeah, you’re not going.”

“The flyers are always trying to make it look like, if you miss this, you’ll die the next day and you’ll regret in the afterlife.”

The flyer was everything, Walshy says and Lee Major—a DJ from East Flatbush by way of Panama and member of Earth Ruler Soundsystem—couldn't agree more. “The first time I was on a flyer, I slept with it,” he says.

In a world without social media, flyers designed by Errol “Irie” Myrie and others were crucial in spreading the word about dances and clashes. While many ‘70s- and ‘80s-era flyers were hand drawn, later posters typically featured the artists clashing in bold colors and typography, with humorous text—a reflection of the movie posters they were often inspired by.

“Just like everything else in life, the way you present yourself, that’s the way it’s going to be reciprocated. So your flyer had to be good, and the top man at that time was Irie Myrie. He took it to a different dimension,” Major says, adding that Myrie and other designers also went to dances to party, see who to put on their flyers and, of course, drum up new business.

Dancehall takes shape in New York

New York’s dancehall scene wasn’t relegated to those now-legendary clubs. Lee Major recounts dancehall parties in basements in the ‘70s and makeshift spaces like barber shops and plazas. “You had to kind of graduate” to the Biltmore, Starlite Ballroom or Act Three, he says. “Those was the arena. That’s when you know you made it, because those are the big platforms … It was definitely a battle, you had to be worthy.”

The Biltmore era of New York dancehall is mythical not only for its epic clashes, but for the diversity of its audience and formidable crews. “There’s King Addies and LP International, Earth Ruler and Soul Supreme. And then you go over to the Bronx, and it’s Downbeat, Stereo Five, and Young Hawk. In Harlem, you got like Firgo Digital and some other sounds. Every sound was on the level,” Walshy says. “It's New York in the ‘90s. You can’t compare it; it’s like everything was happening in a mecca format.”

“It's New York in the ‘90s. You can’t compare it; it’s like everything was happening in a mecca format.”

The dancehall scene developed parallel to the golden age of hip-hop, and influenced the likes of KRS-ONE, Busta Rhymes and Wyclef Jean. The Notorious B.I.G.—the child of Jamaican immigrants whose Bed-Stuy stomping grounds weren’t far from Flatbush’s dancehall epicenter—even did a dub plate for LP International Sound System. “Kool Herc was very influential, because he brought that trademark from Jamaica: the sound system,” Major says, adding that these musical communities largely remained at a respectful distance. “Hip-hop, we integrated, but we never really integrated that much.”

Like aspects of hip-hop at the time, dancehall could be violent. “There were bottles thrown at each side of the place, garbage cans on fire being thrown at each other, gunshots, flinging at each other,” Major recalls of a 1992 clash. “[People at the venue] escorted me out because they said there was people who wanted to kill me. We valued life, but honestly … we didn't.”

Dancehall in the ‘90s “was still underground,” Walshy says. “It was still fire and goddamn dangerous. You know, you literally risked your life for music.”

Dancehall lives on

Today things are more calm, respectful. Crews and remaining soundmen that used to violently clash now support each other’s parties—often at still underground events where OG dancehall fans can reminisce, Major says. Dancehall as a genre, however, has moved into the mainstream: there are dancehall parties on yachts and Sean Paul can pack clubs like Elsewhere. “Queen of Dancehall” Spice has 5 million followers on Instagram. At an average club night, dancehall will be among the sounds of the diaspora, alongside hip-hop, Afrobeats, etc.

But in New York, dancehall culture is still going strong, from more “traditional” parties to DJ nights and more.

Hosted by Hot 97’s Bobby Konders and Jabba of Massive B soundsystem, Fire Sundays in East Flatbush is one of the longest-running dancehall parties in the city. Founded in 2007 as a monthly and now a pop-up event, Rice and Peas is the project of DJ Gravy and Max Glazer of Federation Sound, with resident DJs Maya, Orijahnal Vibez, and the late Micro Don. In Manhattan, the monthly Sattama Sundays has been bringing dancehall, Afrobeats and reggae to the masses since 2003; Yard N Abroad is held weekly on Thursday at Miss Lily's in Alphabet City. Back in Brooklyn, DJ Ayanna Heaven's monthly Good Ting party returns May 10 with a dancehall queen contest and a round robin of DJs, including Lee Major. Sister Nancy, an original dancehall name, performs annually at Union Pool's Summer Thunder series (and recently performed at VP Records' Record Store Day event). And for sound system fans, Dub-Stuy uses its 15-kilowatt stack to highlight a range of Jamaican music—including dancehall.

While they have largely evolved from print-outs and paste-ups to the IG grid, flyers from back in the day still hold a deep value. “It's really like a treasure,” Major says. “My thing is to collect flyers so my kids can see that I had importance, and I contributed to such a major platform.”

A look at Dancehall Flyers

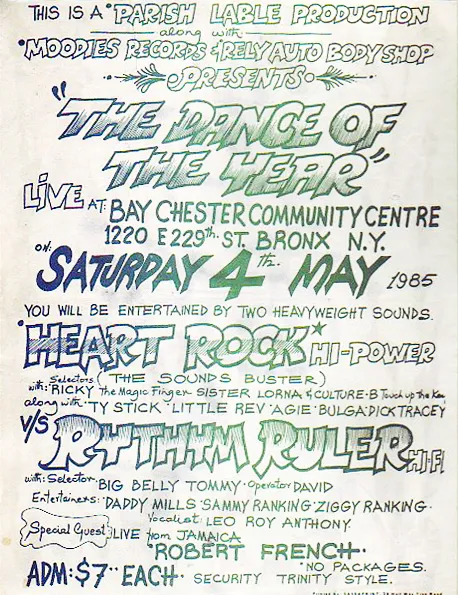

WF: This is the oldest New York flyer, done by Sassafrass, who's the main flyer designer, the most popular, most famous fire designer [in Jamaica]. Everybody would have felt like a piece of home came to the Bronx. There are definitely people who imitated [this style locally].

LM: Dances like those were unique because you may have not heard of some of the sounds as frequent as others. But it was worth going because we always want to hear something new, and something that might give us a different motivation, or different reaction to how they did their clash.

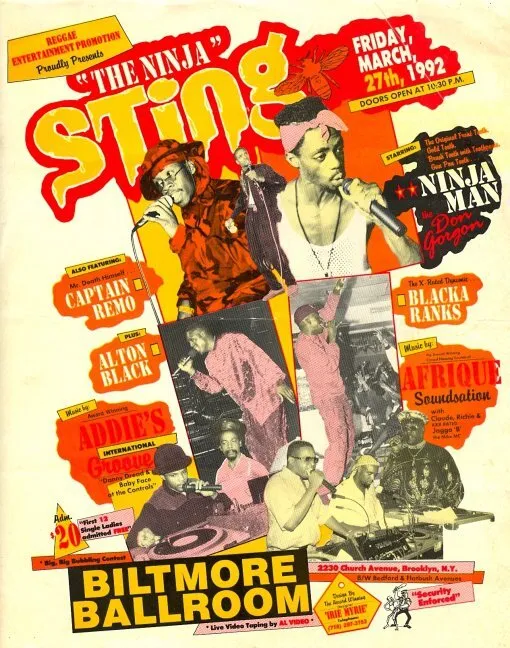

WF: Shaba Ranks would have been probably the most globally known artist, but Ninja Man beat him on stage, and so therefore Nina Man would have been the top artist at this time. Sting is an event that keeps in [December in] Jamaica where the artists clash. So he would have just finished "killing" somebody in Jamaica, you know, winning. This dance would have been like the GRAMMYs.

They were all fashioned after popular movie posters. The Jamaican ones, they almost tried to make the guys during the party seem like actors…. [saying] things like, Leslie as the hairdresser, Eric as the mechanic. It's almost like they're putting movie credits on a flyer.

LM: This was an Irie Myrie flyer, I believe. When Ninja Man came out on stage… expect pandemonium in the place, the energy, and just the craziness. Because people at that time just loved craziness, in a sense of enjoying themselves, letting the hair down, letting their body loose, and just reacting to the input.

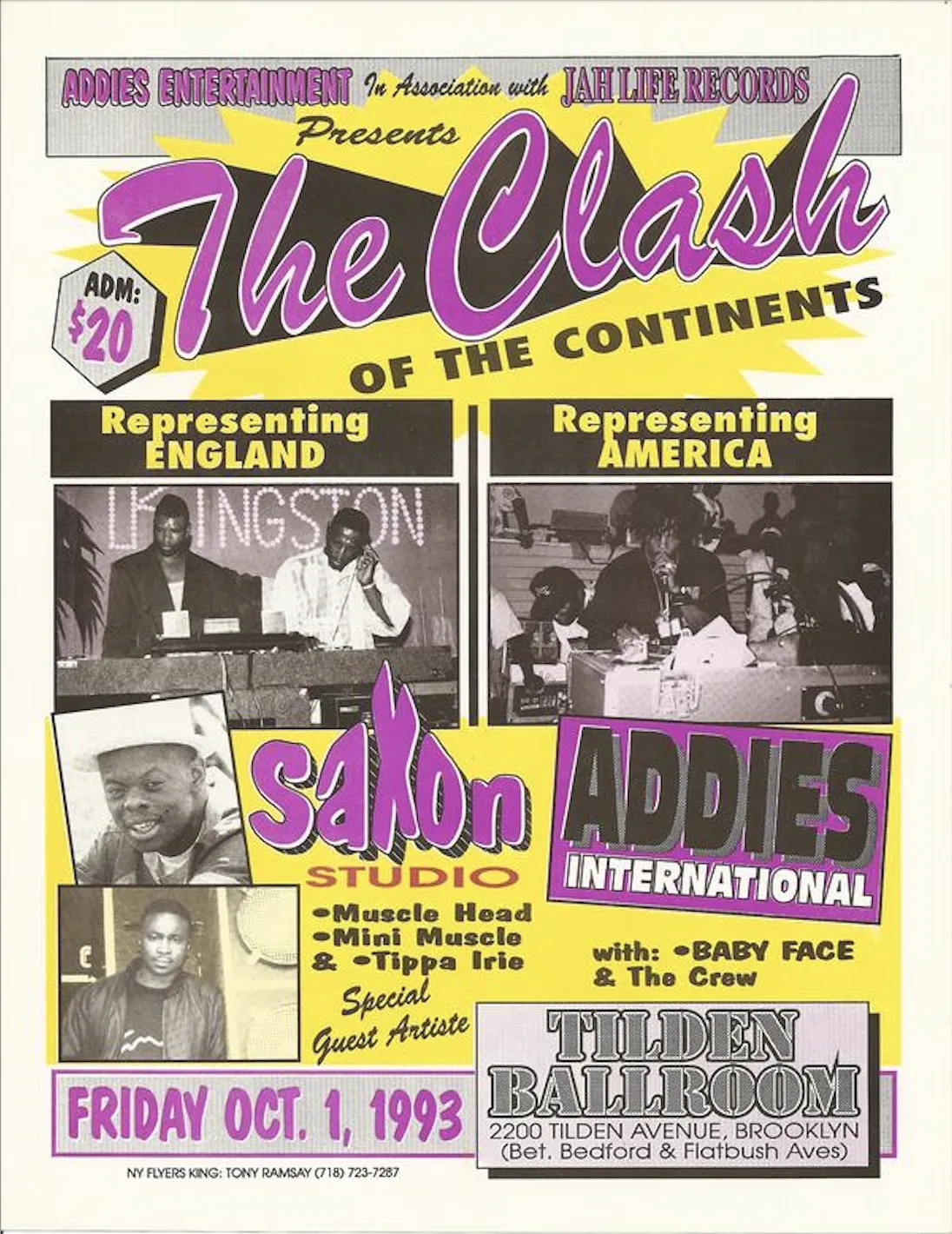

WF: This is a clash that was bigger than something local. This was the biggest sound out of England ever, Saxon Studio, clashing the biggest sound out of New York, out of America ever. This clash would have been absolute madness. [The flyer is] very movie-like; the word clash has this huge bomb explosion behind it. It's a clean, clean, clean flyer.

LM: Addis and Saxon had a historical ongoing clash and everybody was enthusiastic to see the two sounds clash. I grew up on Saxon sound; I was a big fan. I wanted to hear Saxon in New York City. Saxon, at that time, changed their whole way of playing music. Before it used to be artists around the soundsystem and DJ was singing, but they decided to play dubplates so the transaction was totally different.

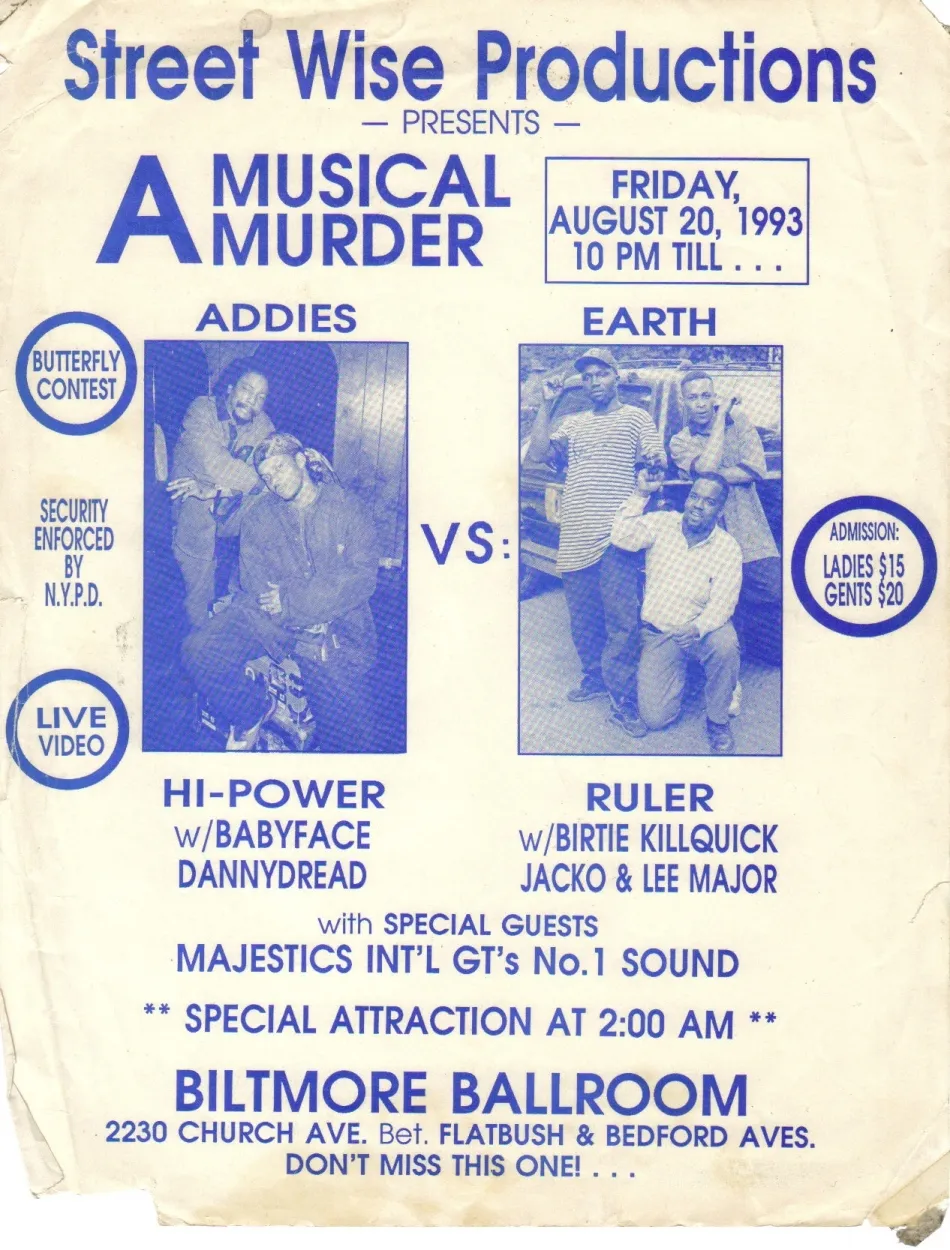

WF: [This flyer shows] how much progression happened really fast. Because if you look at a ’94, ’95 flyer, it’s going to have much more [artistic] advancement in it.

And this was a big, big, dance, huge. It’s a musical murder. The sound is going to die; someone’s going to get musically put to death … kind of like theatrics. There are sounds that did get killed in a dancehall clash and never came back crashing. Is an expensive sport. Those dubplates are not cheap, and once you realize that you don’t have the talent to kill the sound, you might just go, “that’s it. I'm not doing anything else.”

[To actually kill a sound], it would take entertainment, it’d take dubplates, it would take a physical sound system that sounds good. Those are the elements of sound clash, just like hip-hop has pillars, dancehall, sound clash has the same thing: Rhythm, speech, actual sound system and the vocals on the track.

LM: That was a great dance for Earth Ruler … who was the underdog because Addies was a well known, popular sound system with great musical selections and a great DJ. Earth Ruler was the sound that changed the culture when it comes to the juggling part of the music. Earth Ruler was playing records after records after records in a sound clash. We didn’t just play dubplates, we played the regular records to get everybody warmed up for the actual show.

WF: “Longside” means they didn’t clash. “Two champion sounds juggling” is basically a word for DJing to have fun. They probably clashed at the end of the night, because every single night was a “Yo someone’s gonna say something, someone else is gonna respond at the end of the night.” There was not a night that you were not prepared to clash.

Act III is, to this day, the most legendary, infamous club in the Bronx. I had one night where I went there for New Year’s Eve. The night started out with us fighting at the door to get in, fistfighting to get it. It was just one of those amazing youthful nights where you just like, “man, life is so good.”

LM: It was always a longside, but with an underline. Underline like you get too friendly and you step too close, I will step on you. The flyer of course was enhancing it; those times people used to wear linen suits and all kinds of different colors and outfits, and it was more of a dress up affair.

WF: Capleton was the biggest artist at the time. [This flyer] has a pattern in the background, so this is kind of when he was starting to become like a Rastafarian. And the sound that was key to that was African Star. Not too many flyers had, like a pattern in the back.

LM: Capleton, up to this day, is one of the greatest performers you’ve ever seen, and he's always bringing the enthusiasm to the club. He just put a fire on—he didn't have to be mean or ferocious, just expressing let us live a natural life. So anytime Capelton came, there was pandemonium. A lot of artists that turned Rastafari and didn't really make it; he was one of them that made it, because people couldn’t understand all of a sudden change. To see the picture of him, starting to grow his natty was very interesting, because they know it’s real.

LM: At that time, dancehall was really getting out of hand; almost every other dance was getting shot up. So we really advocated for peace in the dancehall. So the local sound systems [got together] to let the people know that, yeah, we may clash tomorrow or yesterday, but all of us are still cool; we’re just competitive by nature. We don’t want nobody to get hurt because a lot of our friends, a lot of people, never came out of a dance.

I respect the fact and I love the fact that a lot of people say they will wish they were down in Biltmore or Starline, but I don't think you really want to be there. Not to say we was walking into a death trap, but I’m just saying it was a lot. You have to have courage. You have to have a heart to go into those arenas and those days.