[title]

You’ve probably seen The Old Town Bar even if you don’t realize it. Images of its tiled floors, reddish pressed tin ceiling and wooden bar have long been visual staples of the American cultural diet. Its neon sign and welcoming interior were emblazoned across the opening sequence of The Late Show with David Letterman. Its other credits include the movies The Devil’s Own and State of Grace, as well as the music videos for House of Pain’s “Jump Around” and Madonna’s “Bad Girl.”

Old Town’s appeal runs deeper than its classic New York aesthetic, however. True to its name, The Old Town Bar has proudly stood on 18th Street between Broadway and Park Avenue for over 130 years. It’s long been a spot where New Yorkers have come to gather, talk and connect.

This fall, I had the privilege of speaking with the co-owner of Old Town, Gerard Meagher, to learn more about the bar’s history, its patron saints, and, of course, its secrets.

A Bar for Everyone

Old Town was originally established in 1892 as a German restaurant called Viemeister’s. The first floor was a saloon for the men while the upstairs dining room operated as a more respectable restaurant for both gentlemen and ladies. To this day, the ladies’ room is still on the second floor while the men’s room is on the ground floor.

For the first 80 or so years of its existence, the fortunes of Old Town were tied to the subway. The restaurant began prospering in 1904 when the now-forgotten 18th Street and Park Avenue subway stop opened, which served the city’s original subway line the IRT. However, by 1920 the bar had been sold and the new owners—who re-named it Craig’s Restaurant—were concerned with surviving Prohibition. They made do, in large part, by fitting their booths with secret compartments under the seats in which they stashed bottles of alcohol for their loyal patrons.

After Prohibition, the restaurant changed hands again and was renamed Old Town Bar – Restaurant. It was a fitting rebranding because, by that point, the bar had become a cornerstone of the neighborhood. A menu from 1937 shows you could buy a pint of beer for a quarter and the special of the day—a sliced steak sandwich on toast with fresh mushrooms and French fried potatoes—for 50 cents.

However, hard times fell on the bar in 1948, when the 18th Street and Park Avenue subway stop closed and the Union Square neighborhood it calls home began to slip into disrepair. The bar stopped serving food and it shortened its hours to 9-5, as its only patrons had dwindled to the union men who worked in the area. The lone bright spot during these years was when Andy Warhol opened his studio, The Factory, nearby. Gerard said that he remembers Warhol, with his unmistakable bob of white hair, frequently patronizing Old Town where he’d sit elbow-to-elbow with tough union men, drinking beer.

Gerard’s father, Larry, began working at the bar around this time. Like many of the bar’s patrons of that era, he was a union man. Larry worked as a photo engraver for the New York World-Telegram and was the union representative. The union’s office was around the corner from Old Town, and Larry began to frequent the joint. Larry liked the place so much he began bartending and eventually bought the bar in 1985. Larry’s tenure coincided with the neighborhood’s revival, and he re-opened the bar at nights as well as reinvigorated the food service—initially relying on a Bunsen burner he stashed behind the bar until he could renovate the second-floor kitchen. Gerard followed in his father’s footsteps. After launching a successful advertising career, Gerard began bartending at Old Town for one night a week until he eventually took over for his father in 2007.

Literary Haven

The Old Town Bar is also writer’s bar. The reason is simple: as Frank McCourt, the Pulitzer Prize winning author of Angela’s Ashes and a regular visitor to Old Town put it: “The king of New York bars—where you can still talk!” That’s not to say the bar has the atmosphere of a crypt—it’s just Old Town understands volume control. The hum of conversation blends in seamlessly with the tunes, creating a melodic undercurrent that buoys and propels conversation.

McCourt wasn’t the only writer to appreciate Old Town’s appeal. In fact, Old Town might be the unofficial bar of Irish and Irish-American writers. The poet Seamus Heaney visited whenever he was in town—he confided in Gerard that Old Town was his favorite bar in New York City. Billy Collins still comes by regularly. Jim Dwyer, a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist and author, has a signed book jacket on the wall. And the late, great Pete Hamill—witty chronicler of the city and an acclaimed drinker turned teetotaler—said that if he were to ever drink again, it’d be at Old Town.

Marvelous Fixtures

For the past 130 years, Old Town has remained a relative secret among both tourists and locals alike. Its location just north of Union Square, tucked between Broadway and Park Avenue, contributes to its low-key nature. But inside there are marvels.

The mahogany bar runs an impressive 55 feet long. At one end sits what may be the city’s largest and best-preserved dumbwaiter, which is still used to ferry food between the first and second floors.

Tucked at the far end of the bar, to the drinker’s right, the old workhouse sits snugly in custom made cabinetry. It has been transporting hot meals from the second-floor kitchen to hungry patrons for as long as the bar has been around.

For fans of such miniature freight elevators, the best seats in the house are the tables in the back room on the right-hand side. From there, you can get a clear view of the dumbwaiter in action.

The Old Town Bar is also something of a pilgrimage site for admirers of great porcelain. It boasts what may be the only two surviving Hinsdale urinals on the east coast. Each urinal stands about 4 feet tall and is nearly just as deep. The tops of the urinals are curved inwards, as if inviting the user to step into an experience. In this way, their silent majesty turns a routine act into something a bit more mystical. The New York Times restaurant critic Pete Wells once commented “They’re so grand they turn the act of urinating into something sacramental.”

Wells is not wrong—the urinals were specifically invented to elevate the experience. The Hinsdale urinals were patented in 1910. Their inventor, a Manhattanite named Winfield E. Hinsdale, wrote that his urinals were specifically designed to “embrace a body” and provide “a more sightly appearance.”

The urinals are an attraction unto themselves. Gerard held a 100th anniversary gala in 2010 to celebrate the urinals hitting the century mark. As fitting with the gravity of the occasion, then-mayor Michael Bloomberg sent a letter to Gerard with his congratulations.

Mystery Monks

If you ever make your way up to the second floor (whether to dine or to use the restroom), look up. You won’t find God in the Old Town Bar, but you may find His servants.

Under the eaves, lit by the south-facing stained-glass windows, sit five weathered murals of monks engaged in all sorts of imbibery. In one, three monks ponder an eel with a telltale beer bottle on the left. One monk lifts his spectacles to get a good look at the eel while the eel looks back in defiance. In another, a lonely monk is splayed out on a chair, glass knocked over—its contents about to drip off the table’s ledge. The culprit, a barrel of beer, sits innocently beside him. Gerard doesn’t know who painted the murals or when they’re from. As far as he knows, they’ve always been here, silent yet animated companions to 130 years of diners.

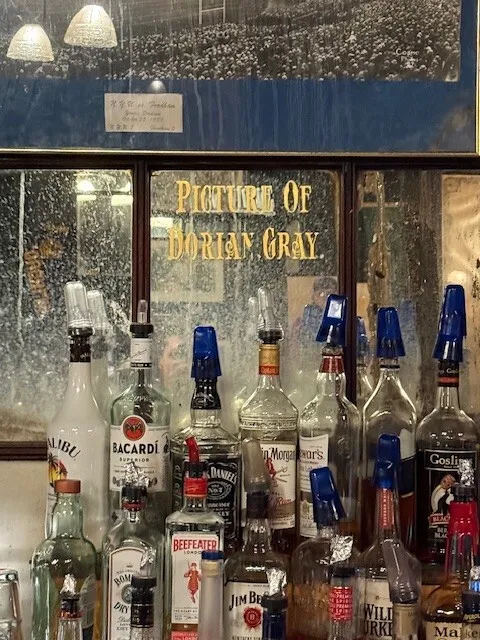

Like any great bar, the longer you stay at Old Town, the more you notice. One glass pane behind the bar is labeled “The Picture of Dorian Gray.” I’d advise against looking into it—especially after a few pints.

A discolored campaign poster hangs high on the wall above one of the booths. If you peer closely, you’ll notice it’s stumping for William J. Meagher, who was Gerard’s great-uncle and the former Democratic boss of Williamsburg. (He won that election.) Noting my interest, Gerard proudly explained that his great-grandfather, Mattie Meagher, was also a political boss in Brooklyn, and the inspiration for the character Mattie Mahoney in Betty Smith’s beloved novel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.

Before I left, I asked Gerard about his favorite aspect of Old Town. His answer came quickly and decisively. “It’s a place where everyone feels comfortable.”

I turned on my stool to look around. Sure enough, Gerard was right. The bar was packed with all sorts of patrons. An ancient-looking gentleman nursed a beer in the corner. Two fathers shared a booth with their adult sons. A stylish couple cozied up to the bar after an afternoon of shopping. A group of friends chatted noisily in the back room. And two young parents sat at a table, feeding fries to a pair of rosy-cheeked toddlers.

Old Town’s recipe for success isn’t hard to divine. In a city obsessed with exclusivity and the next great thing, Old Town has carved out a legacy by being one of those rare, special places where anybody can walk in, order a beer or a hot sandwich, and feel welcomed.