[title]

An Enemy of the People portrays one man's struggle to spread the truth about deadly pollution. Last night on Broadway, in a chaotic example of life imitating art, real-life climate activists literally stopped the show: Three protesters, one by one, stood up and interrupted the play with speeches of their own, leaving the actors and the audience rattled.

I was there, and I was stunned. Truth be told, I didn't know what to believe. It was, if nothing else, a tremendous moment of theater.

I later talked at some length with one of the protesters, Nate Smith. I'll get to that part soon—but first, some background. Henrik Ibsen's 1882 social drama An Enemy of the People centers on Dr. Thomas Stockmann, who discovers that the spa water in his small resort town is teeming with potentially fatal bacteria. Since the local economy depends on spa tourism, no one wants to believe him. The play's Broadway revival, adapted by Amy Herzog and directed by Sam Gold, stars Succession's Jeremy Strong as Stockmann and The Sopranos's Michael Imperioli as his bother, the town's mayor. The production is a hit: It grossed more than $1 million last week, and has been selling out the small Circle in the Square Theatre.

Last night was a press performance, so a lot of critics—including me—were in attendance. The production doesn't open until Monday, so I won't review it here. All you need to know is that, coming out of a brief intermission, the play depicts a public forum at which Stockmann attempts to tell his fellow citizens what's going on, and they turn on him violently. The entire play is staged in the round, and in this scene Gold's staging consciously includes the audience. Multiple spectators are brought onstage to pad out the action; the house lights are kept on, and the actors address the crowd as though we were townsfolk at the meeting.

The protesters could not have picked a more appropriate moment for their protest. It began when a young man, wearing the logo of the activist group Extinction Rebellion, walked down an aisle of the theater and started talking loudly. "I object to the silencing of scientists!" he began. "I am very very sorry to interrupt your night and this amazing performance." As he went on, the actors onstage grew increasingly agitated but tried to stay in character; one of them, David Patrick Kelly, went into the aisle to confront him. "The oceans are acidifying! The oceans are rising and will swallow this city and this entire theater whole!" the man continued. By this point Imperioli had joined Kelly in the aisle, and the two of them were pushing him out of the theater. "The water is coming for us!" he yelled as he was escorted from the room. "Broadway will not survive on a dead planet!"

The New York chapter of Extinction Rebellion later posted a video of this moment on X. You can watch it here:

🚨#BREAKING - Rebels disrupted #AnEnemyOfThePeople on #Broadway. #Climate activists aren't the enemy; it's fossil fuel criminals like Exxon & Chevron. If we don’t #EndFossilFuels now, there'll be #NoTheatreOnADeadPlanet [THREAD] pic.twitter.com/9oFHSrzAMb

— Extinction Rebellion NYC 🌎 (@XR_NYC) March 15, 2024

Throughout this episode, as you can see, the audience just listened. Most of them probably thought, as I did, that this scene was part of the show—a wall-breaking flourish intended to link the play explicitly to modern concerns. The actors remained more or less in character; Strong, as Dr. Stockmann, even said something to the effect of "He's right!" I've seen many plays in which performers pose as audience members and interrupt the action in a similar fashion. I was sure that was the situation here, and I appreciated what I thought was the director's intent, even if it seemed a little stagy. "Ha!" I wrote in my notebook. "Cute metatheatrics!"

The actors onstage resumed the scene—but the protest wasn't over. A woman on the other side of the crowd soon rose up and started yelling about the environment; she, too, was dragged away, shouting the names of Tim Martin and Joanna Smith, two activists who were arrested last year for smearing black and red paint on a Degas sculpture at the National Gallery. The audience remained mostly quiet, but there were now scattered boos directed at the protester. The tide of the room was shifting.

When a third activist stood up and started shouting, much of the audience shouted back at him. He was in the middle of a row, and harder to silence. On the voice-over advice of stage management, the actors cleared the stage. "Go back to drama school!" yelled Imperioli in his dismissive mayor persona. "This is not the place," yelled someone else. "You gotta write your own play!" yelled Kelly, to applause from the crowd. The police were now present. "You got to go! You got to go!" Kelly repeated as the third protester—chanting the slogan "No theater on a dead planet"—was forcibly removed.

You can see part of this third exchange on this video posted on X by an audience member:

more from an enemy of the people tonight!

— nitsi | succession broadway era ! ♡ (@hosseinisgeckos) March 15, 2024

via: 📸: oseh11 pic.twitter.com/TUQJMU3MLP

And that was that. The protest was over. The actors returned to the scene, and the townspeople turned on Stockmann.

The attitude of the videographer above reflects that of the room in general: "Can't stand these protesters man they are the worst 😂😂." The crowd's opinion of the disruption had changed, and so had mine. I still thought the whole thing had been staged by Gold, but I no longer thought it was cute—I thought it was brilliant, and chilling. What an effect! In the middle of a scene about a large group rejecting a teller of inconvenient truths, Gold had engineered the audience into shouting down people who were trying to share an urgent message about poisoned water. The whole thing had taken less than 10 minutes. I was shocked at how easy it was to whip a pleasant group of Broadway spectators into a jeering mob.

I loved it: It seemed an ideal illustration of what Ibsen was saying. It was only later that I found out that the protest wasn't staged. An Enemy of the People's press reps confirmed as much when I wrote them to ask—"It was a real protest that has never happened before since performances began"—and at 11:40pm I got an email from Extinction Rebellion.

"This action follows a tradition of nonviolent civil disobedience in arts and theater, such as Parisian students’ occupation of the Odéon theatre in 1968—not to mention theater itself as a powerful medium for provoking social change," the group's press release explained. "Today’s action highlights the failure of governments and corporations to treat climate and ecological breakdown as the crisis it is."

But why this show? "Just as An Enemy of the People demands people act, Extinction Rebellion too is demanding immediate action…Extinction Rebellion demands the government tell the truth by declaring a climate and ecological emergency, halt biodiversity loss and reduce greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2025."

But why now? "The climate and ecological crisis threatens everything on our planet, including the theater. This action and similar actions are the response of a movement that has no other recourse than to engage in unconventional means of protest to bring mass attention to the greatest emergency of our time. All normal means of affecting change appropriate to the scale of the catastrophe—including voting, petitioning, lobbying, etc.—have failed and continue to fail. Yet the science makes clear that we have only a very small window of time in which to transition from fossil fuels and stop carbon emissions."

"Theater-as-usual won't be possible on a planet in which humanity fails to keep global warming below 2 degrees Celsius," the press release continued. "If activists don’t disrupt these shows, dangerous weather will make it impossible for the show to go on."

This last part lost me a little: Disrupting shows doesn't seem like an effective solution to the problems described. And I'm certainly not in favor of further disruptions of An Enemy of the People, or any other production. (I was already annoyed enough at this performance by someone unwrapping a candy very, very slowly in the seat behind me.) But this one particular disruption, at this one performance, struck me as kind of perfect. So I wanted to find out more about the people behind it.

I reached out to Extinction Rebellion and they connected me with the first protester to speak up at An Enemy of the People: Nate Smith, who identifies as a theater artist. At a little past midnight, we talked on the phone. Here is our conversation (edited for brevity and clarity).

It looked like the police showed up. What was the aftermath of this disruption for you and the other protesters?

I really can't say what happened with them—I left immediately, I didn't see. But there were no arrests.

One of the things that was interesting for me as an audience member was that I really wasn't sure—because of the timing of the interruption—whether it was part of the show or not. Because that scene is already a public forum.

Yeah, yeah. You saw the way the lights were up and all of that. Sometimes the audience is already woven in with the play from the start, but it’s different to just turn the lights up and have some of the audience come onstage. One of the reasons for this play being the focus in the first place is that I can't think of a better play as a metaphor for what we're going through with the climate crisis. And the treatment of Dr. Stockmann—people have been equating it with Covid because that’s been so front-page and headlined, but the play is really about ecological, water-based poisoning. So for that part to be layered and very meta was conscious.

When you got up, you mentioned that you were a theater artist and you said something about the space.

I think I said some words that might have been misunderstood. I work in theater in this city but I didn't mean in the theater that we were at.

Were you thinking about this protest in performance terms?

We knew that it would impact the meaning of the play from then on—to watch the treatment of this scientist who's trying to say something to an audience. That was part of the intention: How are you experiencing the rest of this piece? People got more and more upset. And we knew that when they got to the climax of the play, it would resonate differently based on what had just happened live.

I was kind of disappointed when it turned out that the protest was not actually part of the play, because I found the audience reaction fascinating.

Afterwards or just during?

During—I mean, afterwards the audience basically settled back into the play. But during, it was like an experiment in crowd psychodynamics. What was your experience of the audience's reaction to what you were saying?

I got my Bachelor's in rhetoric, so I had a really clear intent: I really wanted to not have the audience yelling immediately—to stave off the boos. So I knew that I wanted to start off with an apology. I mean, people are gonna be mad, and that's entirely understandable. Of course you're gonna be mad if you're taking it in for fun, and these are expensive tickets—all of that. Why are you throwing soup on this piece of art? But I knew that there would be a way, both with the apology and with the meta quality, to weave it in with the show, to maybe not have that reaction right away. I very much expected to be stopped very soon. But I was happy that my intent—Can I make enough eye contact with people and maybe be confusing enough to not have people automatically yell at me?—was a goal that was achieved. I saw some people really listening: By the time I was talking about the oceans rising, even though there were cast members yelling at me to shut up, I saw some people really listening to me. To see Jeremy Strong looking so happy and saying “He's right!” [he laughs]—that plus the people in the audience who were really listening, and the fact that I didn't hear anyone yelling at me besides the other cast members (which, again, is understandable) was a big victory to me.

You talk about not interrupting the art or throwing soup on the art—but another protester yelled out support for Joanna Smith, who was arrested for throwing paint on a Degas. Is that action something you identify with?

We were definitely standing in solidarity with all of the activists who are starting to undergo the treatment that climate activists are being treated with. I think protest is under threat in a lot of countries. But specifically Joanna Smith and Tim Martin with their Degas action—which did not permanently damage anything and wasn't violent in any way, but as mild as nonviolent direct action gets—they were charged with conspiracy to commit an offense against the United States, which is absurd. And Stop Cop city activists are being charged on a kind of unheard-of RICO conspiracy charge. There’s an escalation. ALEC, a highly funded group that writes legislation that is sometimes just copied and pasted in Congress, is seeking to drastically increase charges for climate action, especially fossil-fuel infrastructure damage. This has been happening a lot in the United States. Even just since the BLM movements, a lot of Republican states passed some pretty heinous, and I would say dangerous, attacks against the right to protest and to ask for redress of grievances. It's concerning, and I would assume that it is all only going to get worse, especially if we don't have an appropriate response. So we thought that it was important to call for an end to this persecution. In the case of Joanna Smith, of the Degas Two, they’re awaiting their trial, I believe, so we wanted to stand in solidarity with them.

As a theater artist yourself, though, didn’t you feel bad disrupting a theater work?

As an actor, I don’t want to offend other theater artists. The last play I produced was an Amy Herzog play! So it's not at all about disrespecting these amazing artists or this work. Theater has a long history of answering to social times, but I don't want there to be the confusion of “we're attacking the art.” It's not the art that we are attacking. And I am happy to think that we are going to contribute to ticket sales for the play, ’cause I do think that it's something everybody should see.

An Enemy of the People is playing at Circle in the Square through June 16. You can buy tickets here.

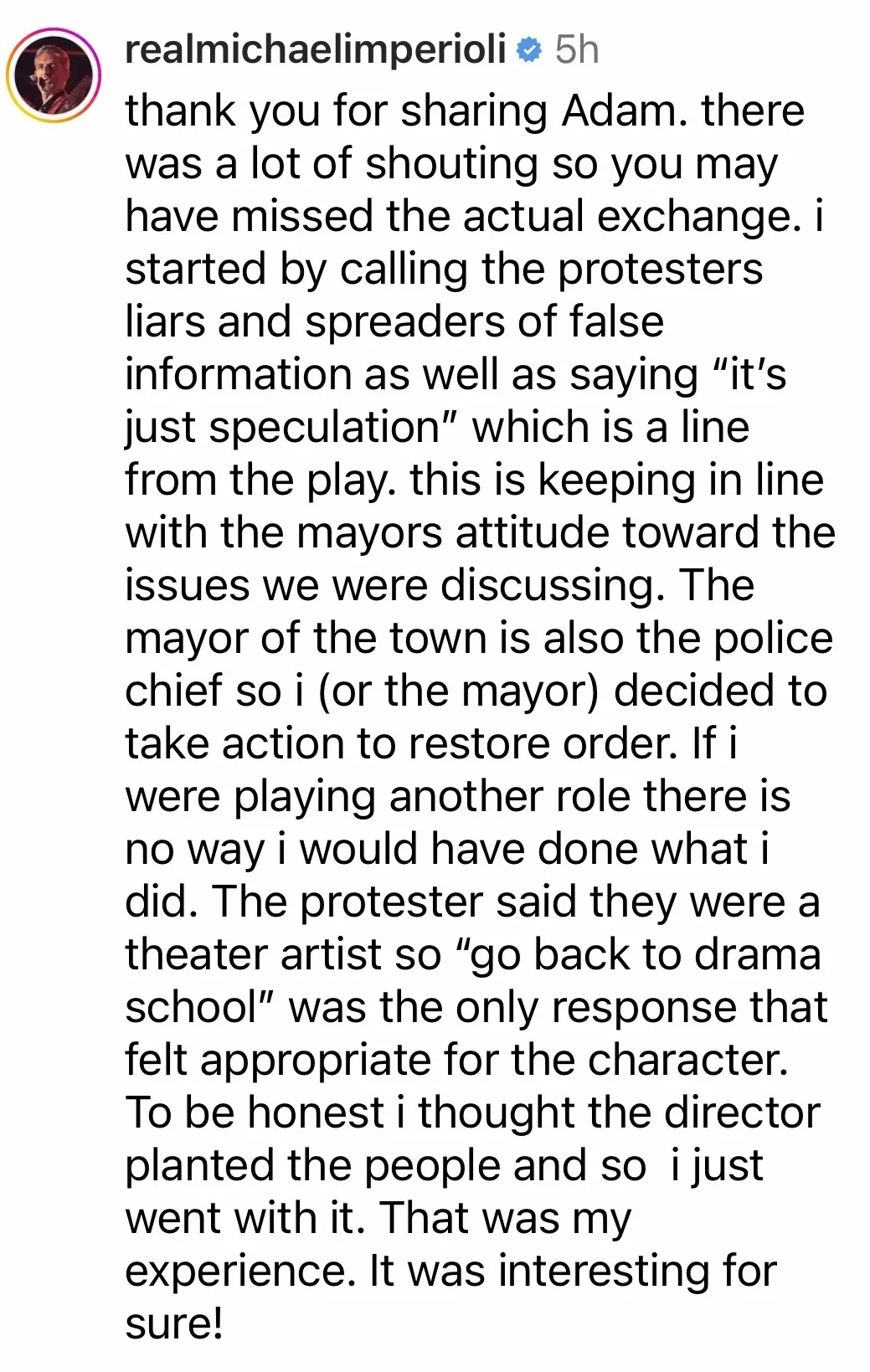

UPDATE: Michael Imperioli posted about the incident on Instagram: "tonight was wild…" he wrote. "no hard feelings extinction rebellion crew. michael is on your side but mayor stockmann is not. much love." (See below). In a comment on my Instagram post about this story on Friday, Imperioli elaborated further on this point: "thank you for sharing Adam. there was a lot of shouting so you may have missed the actual exchange. i started by calling the protesters liars and spreaders of false information as well as saying 'it’s just speculation' which is a line from the play. this is keeping in line with the mayors attitude toward the issues we were discussing. The mayor of the town is also the police chief so i (or the mayor) decided to take action to restore order. If i were playing another role there is no way i would have done what i did. The protester said they were a theater artist so 'go back to drama school' was the only response that felt appropriate for the character. To be honest i thought the director planted the people and so i just went with it. That was my experience. It was interesting for sure!" (See below.)

View this post on Instagram