[title]

When you think of Franz Kafka, there are a few words that likely come to mind: Lonely, tortured, isolated. But this depiction doesn’t actually tell the full story of Kafka, a new exhibit at The Morgan Library & Museum argues. Yes, the Czech writer known for his surrealist literary masterpieces like The Metamorphosis, did have a difficult life before dying at the age of 40 from tuberculosis.

But he was also known to be funny, a brilliant love letter writer, a good friend, and even a playful spirit. In fact, many of the solo photos we see of Kafka were really photos with other people who have been cut out of the scene over the years, Sal Robinson, curator at The Morgan explained during a tour of the new exhibit. The show, simply titled "Franz Kafka," is now on view through April 13, 2025.

RECOMMENDED: The best museum exhibitions in NYC right now

The exhibition charts Kafka’s life from the very beginning. Born in 1883 into a German-speaking, Jewish family, he spent his entire life in a small section of Prague living with his family in a small apartment. They faced constant financial instability and Kafka, in particular, struggled with his aggressive father and noisy disruption in the small space.

You can see a scale model of the family’s apartment in the exhibit.

As Kafka grew older, he took on some unusual health practices, Robinson said. Each day began with a precise exercise routine—a ritual that often made him late for work to his job as a legal writer in insurance. Kafka was so good at his writing job, that his bosses forbade him from enlisting in World War I and gave him extended sick leave when he fell ill with tuberculosis.

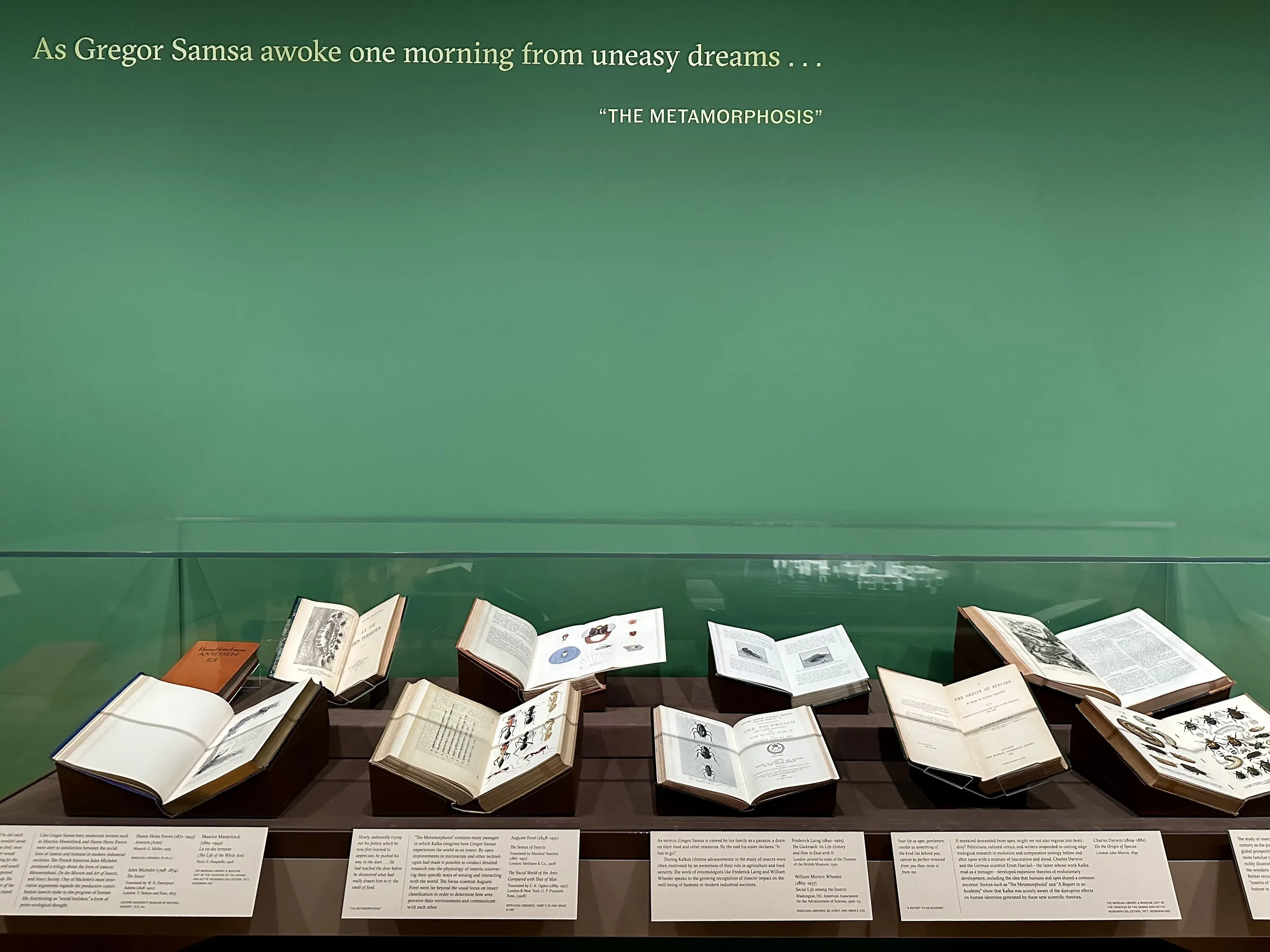

After working his day job, Kafka would write in the evening. The Metamorphosis, for example, was something he wrote over a series of nights in 1912. You can see the original manuscript at The Morgan; be sure to notice how the first few lines emerge almost fully formed with swift penmanship, showing his rush to get his ideas onto the page. The exhibit also digs into other famed Kafka works, including The Castle.

Though Kafka was engaged multiple times, he never married. Today, he's become an icon on TikTok where women swoon over his love letters and declare Kafka as their boyfriend. Though the exhibit doesn't touch on that legacy, Robinson said in an interview that she understands the writer's enduring appeal.

"I think the reason he had so many relationships with women was that he was incredibly engaged in their lives and sympathetic. He wrote beautiful love letters," Robinson said. "He really wanted to know what your life was like, what you were feeling, what was happening to you every day, every moment. And that's very, very appealing."

She's just happy people are reading literature. The late writer might be surprised, however, to know that his works have found such an audience. At the time of his death in 1924, Kafka had published only a few novellas and collections of short stories. He left behind a collection of unfinished novels and a mass of stories and personal writings. He left those works in the care of his friend Max Brod with instructions to "burn all my diaries, manuscripts, letters ... completely unread."

Obviously, Brod did not listen—a gift to us all. As Nazi forces advanced on Prague in 1939, Brod escaped on the last train with Kafka's papers in hand. He made sure to keep Kafka's work safe in the years following.

"My decision [rests] simply and solely on the fact that Kafka's unpublished work contains the most wonderful treasures," he's quoted as saying.