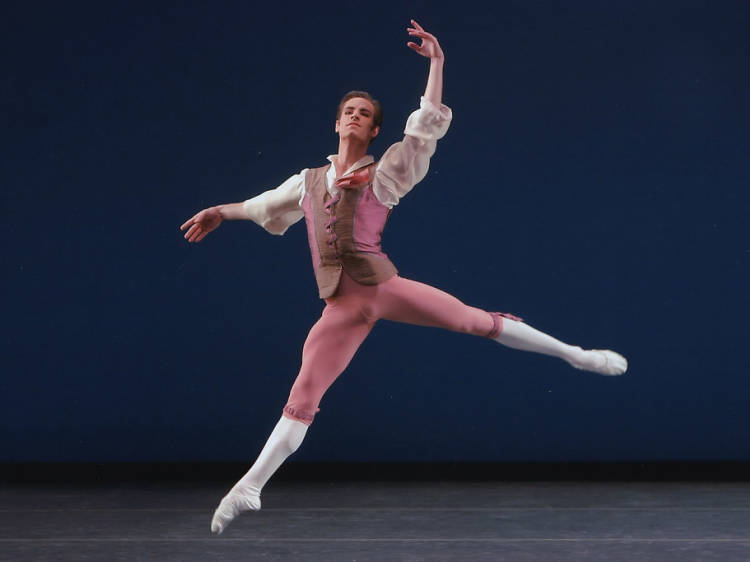

There are vivacious dancers and there is Andrew Veyette, whose ebullient spirit carries through in all of his roles at New York City Ballet. A principal since 2007, the sandy-haired dancer just finished a round of Nutcrackers. Now he has a busy season ahead: Along with leading George Balanchine’s enchanting Harlequinade, he’s cast in Justin Peck’s newest ballet, set to Aaron Copland’s Rodeo. In it, Veyette is paired with Gonzalo García: “We do pretty much everything together, and I just give him grief,” says Veyette. “Everyone is waiting for when Gonzo’s going to slap me.”

How many of Justin Peck’s ballets have you been in?

This is my third. It’s nice to work with somebody who knows what they’re after. I’m not terribly creative with making up steps or interpreting all the time, so I can struggle when somebody’s like, “Do something kind of like this.” I’m like, “I don’t know. How do you want it to be, like this?” I appreciate how specific Justin is—he’s always got a clear idea of what he wants and how he wants it to happen.

How did you find out you’d be in his new ballet?

I’m always pushy with him about it. [Laughs] When he did his last one and I wasn’t in it, I was like, “Hey man, what happened?” Just messing with him. He’s a couple of years younger than I am, so I’m like, “I remember when you came in. Whatever, son.” In reality I’m super impressed with how talented he is. I heard he was doing a new ballet, and so I was like, “Am I going to be in it or what? You didn’t pick me last time.” He was like, “Yeah, you’re gonna be in it.” We laughed because it’s kind of rude. You really shouldn’t be putting that kind of pressure on a choreographer.

Does the new Peck have a story? I’m wondering because of the music—Rodeo was famously choreographed by Agnes de Mille in 1942.

I don’t really think so, but I haven’t seen all of it yet. It’s so brave that he’s doing Rodeo. It’s such a crazy-famous piece of music. I’m like, he is ballsy. I’m sure when it’s all said and done there’s going to be some sort of dialogue happening. It’s 15 guys and one girl, so there’s got to be some kind of story.

How did your dancing change once you became a principal?

I see it clearly now that I’m older. When I was younger, there was a lot of pressure—was I going to be good enough for the role I was doing? If they’ve given you a role, it’s because you’re capable of it. Really, the best thing you can do for the audience is to try to enjoy yourself in it and trust that you’re worth watching—any amount of forced performance is not as nice to watch as someone who’s just being genuine and honest. I try really hard to enjoy the steps and mood. The biggest difference these days is that I don’t get puffed up and worried as I walk out onstage. Self-correcting in a performance is the worst thing you can do, and there were a couple of years when I was struggling to execute the way I wanted to.

How so?

I was so obsessed with executing well that I would go to do a turn, and I would be listing corrections in my head of things to think about. I would be having a whole conversation with myself while I was trying to perform. One day I realized, That’s why you can’t do anything. I always compare it to golf. When you play golf, they say you should have one swing thought, max, when you’re taking your shot, but if you’re thinking, Shoulder, hips…you always hit a bad shot. The best shots are when you’re not thinking about anything at all. I realized one day that’s exactly how it is to turn, to dance. The second you start analyzing it in the middle, it goes to absolute crap. There are parts that I’ve gotten better at, like Theme [and Variations]. I usually survive it pretty well because I just listen to the music, but there are other things I do where I start torturing myself.

Like what?

I always do that in Nutcracker. I don’t know why I have a hard time turning in Nutcracker. I think it’s because we don’t actually dance very much in it. It’s like, you’ve gotta get three steps right, and if any of them go poorly then you feel like you didn’t dance well. [Gravely] But you know, I’m an old man now—32 is not really old, but it is old. I’m trying to enjoy it before something goes snap.

How old is 30 in ballet?

When you hit 30, your body feels different immediately. I’m in decent shape, but it takes a lot more work for me to feel like I can get to where I could when I was 25. Your legs just don’t fire the same way. You have to use technique and stamina to accomplish things—when you were young, you just threw yourself in the air and everything went pop. I don’t feel terrible yet. But in the back of my head is the reality that the things that I dance here ask a lot of my body.

Even though you’re an old man, do you find a different pleasure in dancing now?

It’s enjoyable now. There was so much stress and pressure before, and I was so worried. I’d wanted to be doing more and getting promoted so much sooner than I was, and I felt it was my own fault that I wasn’t on a faster track, so everything I did when I was in my early twenties was so loaded with pressure and guilt and paranoia. The only thing I worry about now is that they like me, and I get lots of wonderful rep, to a degree sometimes I don’t know if I want this much. I have to be careful that I don’t vocalize that too much, because I don’t want to seem ungrateful. I’d like to avoid feeling like I’m in survival mode.

What is your history with Harlequinade?

I’m really excited it’s coming back, because it’s the part that broke my career open. I was struggling to do something really well until I did that ballet. I first danced it in Saratoga on really short notice. It was Alexandra [Ansanelli’s] last show with the company. I really liked dancing with Alexandra. Our energies matched, and I understood how to partner her. In Harlequinade you put on makeup, a mask and a skullcap and a crazy costume, and I almost think part of why I did it so well, aside from the fact that the steps suited my body, is that I was hiding in a character. I didn’t have to be good as myself.

Before a season starts, do you evaluate yourself? Do you think about what you’re going to work on?

I guess I do. One of the downsides of having a month and a half worth of performances to do is, by the end you’re trying to just continue to accomplish each show and you’ve fallen out of, What kind of shape am I in? I always do try to evaluate the age I am going into a new season and the way that’s affected my body. Older men have bigger butts and thicker thighs—we look different. I think about, Can I improve my flexibility and the way I’m working to try to maintain a nice shape, particularly to the tops of my legs? Can I afford to gain any muscle up top? I like to be around 155 [pounds] when I’m performing, which is pretty challenging for me because it’s pretty small. Right now, I’m probably 158 or 160 and I’m like [He slumps over and mimics slitting his wrists.]

Oh no!

I can’t expect myself to be 150 pounds like I was when I was 23. I have to evaluate, How can I work out and build my body in a way that I’ll be happy with the shape of it without starving myself? I have really busy days—I can’t not eat a decent amount of food and expect to have energy to do my job. After 30, you can’t really eat the way you used to, but you also can’t live on nothing the way you used to. If I needed to lose three or four pounds when I was 20, I just didn’t eat lunch or breakfast for two days, and I lost five pounds. If I do that now I can’t get through my day. But I’m never really happy with how I look until I’m exhausted. Sterling [Hyltin] and I were laughing that our last Nutcracker last season was on a day that we were completely worn out. We were so tired that we couldn’t get in our own way for the show, and it was the best one we did all season. We just looked at each other and were like, Well that's annoying.

I want to know more about golf and ballet. First, do you actually play golf?

Jonathan [Stafford] and I started playing five or six years ago. We’re okay. Jon’s a little bit better than I am. We’re both in the high 80s.

Just how is golf like ballet?

It’s like I was saying—you can’t get in your own way. You do all the practicing and you warm up before you play. It’s so much like a performance except it’s four and a half hours. For every shot you’re taking, you have to clear your head and allow it to happen. In ballet, if you want to perform well, you just have to let yourself do it. You can’t force it. The good shows I’ve had were when I was tired and didn’t get in my own way, and some of the best rounds of golf I had were when I was exhausted because I was up late the night before and then up early to play the next day. Jon and I started playing more and more because as my rep and my schedule got harder, it was hard for me to bike for 20, 30 miles on my day off, but rolling around on a golf cart and hitting balls…

Wait—you use a golf cart?

Yeah, I’m not walkin’. [Laughs] And all the old guys on the golf course give me a hard time and say, “Come on, young man,” and I’m like, You’re not doing what I’m doing all week. I’m sitting down.

Has golf helped your dancing?

I really think it has. It’s definitely helped me turn better. I think there’s nothing as similar to turning as taking a golf shot. You have to set yourself up right, and you have to have a routine, but once you go into the shot you have to let it happen the way it’s going to happen. Every swing and every turn is going to be a little bit different, and you have to trust your set-up and your practice—that it’s going to be there when you need it. Like I said, in golf you’re supposed to have a single-swing thought. Some people are thinking about their shoulders or the angle of their wrist, but if you have five thoughts you’ll turn into a robot, slam the club into the ground and you won’t hit a good shot. It’s the same as when you’re trying to turn. If you’re thinking, Turn my knee out, square my shoulder and spot my head, there’s too much going on. You need one thing. Maybe your spot, maybe where you’re putting your passé. You can change up what you’re thinking about, but never more than one.

See the show!

Discover Time Out original video