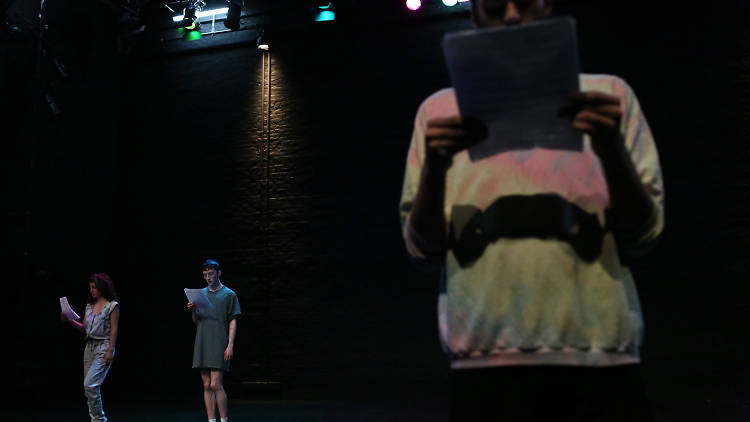

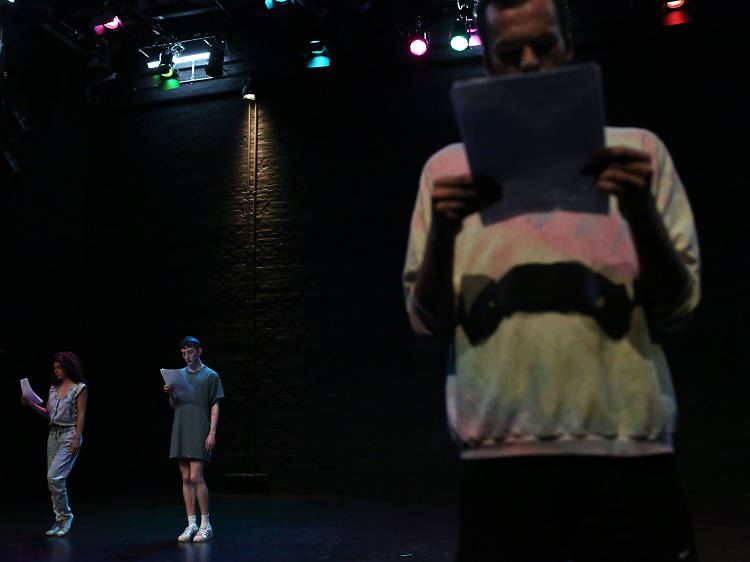

Gillian Walsh is not anti-dance. What is off-limits is artifice. Her unflinching choreographic approach, in which movement is developed through a written score of language and numerical codes culled from mass-produced sources like Hasbro’s Twister Dance Rave, is a love letter to form. In her first evening-length work, Scenario: Script to Perform, featuring Maggie Cloud, Nicole Daunic, Mickey Mahar and herself, Walsh highlights structure over effect. Curated by Sarah Michelson, Scenario is transformative but not glossy, going beneath the surface to absorb the space it inhabits. “I’m kind of a structure pervert,” Walsh says. “I’m always going to see form first.” Be patient; the rewards will come.

Your title is great. How did you come up with it?

It took me ages. There’s a book called Scenarios: Scripts to Perform. All the material in it is mass-produced or mass-circulated. We were interested in mass dance or corporate choreographies. It’s just a book of scores. I love it because of how nondidactic it is and because of its commitment to the score in the abstract.

How did this start?

Maggie Cloud and I did a piece at Judson, where we first decoded the base material. We wanted to do a noncreative Judson [piece] where I wouldn’t choreograph anything.

And the base material was from the Hasbro game?

Yes. It is really what the movement is. We talk a lot about seeing what’s generated from form without super visual theatricality. Any time there’s a technique, there is artifice. But there’s always that big jump between the process and the performance, where it becomes really extroverted—it just becomes the demonstration of the thing that used to be an idea.

How so?

I was thinking about how everything was a sham, with theatrics on top of nothing to prove some conceptual point that has nothing to do with the form. And then we were decoding this game that’s meant to be super fun but produces—if you’re not adding the smiles and the lights—nothing.

How do you regard your scores?

The score is really just a way of orienting the performers. It’s a way for us to work together. I write them alone and make all of the structural decisions, and we learn them together. The score is the master. That allows the group to function together in a specific way. It also removes a perverted choreographer-dancer dynamic that I don’t want to be part of. I’m interested in what’s created in that space when the performers’ energy is really present, but moving in the direction of form—and in our collective understanding of what the form is—rather than pandering to entertainment.

Why is form so important to you?

It’s good to look at form, choreography, dance and physical practice separately. I’m interested in questions of how to locate artifice, the relationship between metaphor and form, mechanisms and structure; it just makes sense to leave dance or physical practice on the side. I’m always going to see form or structure first, and things are going to look excessive to me. And I’ve gotta work on that. [Laughs]

Is that a bad thing?

No. It’s just my brain. I’m not interested in performing subjectivity and using subjects in service to form.

So many people do that.

That’s what it’s about right now. Maybe it always has been. The thing you can see it striving for is a theatrical arc. Even if it’s embedded somewhere deep, it’s still a borrowed theatrical arc that is of a different nature than the form itself. It’s hard to talk about the essentials of form, because we’re not striving for minimal, either, and that’s tricky.

Do you repeat the score, like you have in the past?

There’s repetition. You need a ton of time for the thing to happen. There’s a way of relating—after you’re in the score for a long time, something can happen. [Laughs]

How do you choose your dancers?

I like to work with people that I can talk to. A lot of the work is talking, and we need to be on the same page about its ideas. It’s important that they don’t have secret, repressed performer fantasies that they want to live out through this work. Because even a constant down-turned gaze can’t hold back a truly extroverted show pony’s desire to “perform.” In this piece, where I am so not interested in the demonstration of performance of subjectivity, extroversion and theatrics, the presence of that energy kills the group and the work instantly. But I don’t like talking about what the work can produce, because once you know what it produces, there’s the trap of imitating that thing. I feel very fearful of that.

Right. You have no endgame?

No. The way we approach working is the work. There’s so much in the space between process and the show: That jump to the finished, framed version is not what I want to show. The relationship between looking at the score, understanding it and doing it—that’s the action. Otherwise it’s just a dance. It’s so embarrassing to talk about it.

Why?

I feel meditative and transcendent about it. I have no words; I just have feelings and energies about the vibration of it. It’s introverted. I’ve been trying to figure how to make a dance without lying or dealing with superficial choices.

What is lying?

Being representational is lying. It always needs to be generative. Once I know what it’s going to produce, I have to change it. Also, the work would die. It’s not very energetic, so if it’s dead from the inside, it will kill everyone in the world. I have no interest in that. [Laughs] I’m treating dance a little bit differently, and I don’t mean it as an assault to dance at all. I love dance.

See the show!

Discover Time Out original video