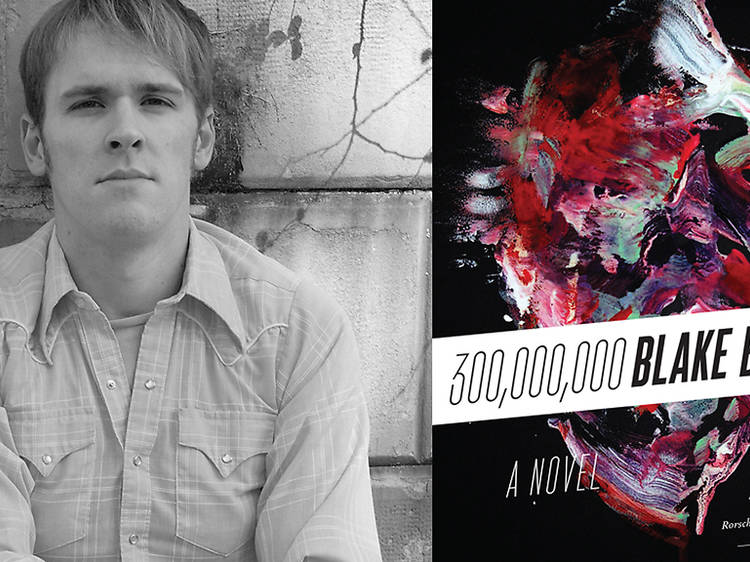

Let's be clear: Blake Butler's writing is not for everyone. His books are somber, often sinister, and filled with unusual strings of syntax and mind-boggling stories that resemble nothing you've read before. Whether writing about unexpected strangeness plaguing a family's new home in There Is No Year or disappearing parents in Scorch Atlas, Butler consistently pushes his readers' limits and defies the laws of fiction we had taken for granted. In his latest, 300,000,000—one of our top books to read this fall—the author invents a serial killer, Gretch Gravey, whose malevolent persona infects the United States like a plague, bringing about the end of the country when the populace turns on and kills itself. That's right: Everybody in America dies in this haunting portrayal of violence.

I caught up with Butler to discuss the book, getting into the mind of a murderer and his feelings about the word "sternum."

I always like to hear about a book's origins. What was the spark of this novel? And how long did you work on it?

It was a low time in my life. I felt like I'd lost everything and was kind of living in a blind mania, though at the same time bored, unsure what to do with myself. A friend and I had a conversation about how many entertainments these days are centered around violent murder-cop shows, explosion movies, serial killer lore-and how flat the effect of it has become. He said I should write a book that blew all that out of the water, in so many words: the end of the murder story. That idea fit well with how I felt. I applied my energy, at first, in trying to outdo a book I'd heard a lot about around then, Roberto Bolaño's 2666, which everyone was describing as this grisly, brutal masterpiece. I read the book and actually liked it, but it turned out to be nothing at all like what I envisioned from its reputation, so I decided to try to write out that imagined book, to max out all my powers and frustration into the ultimate thing I could. I worked on it almost every day for about two years straight, then spent the next two years revising, finding ways to open it even further, until I couldn't anymore. In the end, it bore little relation to 2666 and certainly requires no familiarity with it, but it was good to have something to model, even if my goal ultimately was to obliterate it.

How much research did you do into the behavior and psychology of other serial killers to inform the Gretch Gravey's character, his actions, and, especially, his notebook writing, which begins the narrative?

One of the things about the voice of the opening section of the book in particular is that it contains many voices stuffed into one voice. The narrator has this idea that the whole world should be condensed into a single body, until there is only one body in the world left, literally cannibalizing one flesh into another over and over, which he intends to accomplish basically by infecting people with his persona, like a virus. Besides feeling like I had multiple personalities myself during this time, I got a lot out of milking the language of famous viral personas, in particular Koresh, Manson, Dahmer, Dahmer's father Lionhel, Ramirez, etc. For example, when I really wanted to change the condition of how I was speaking, I would take a sermon Koresh had given, and chop it up as columns in MS Word, and see what weird sentences would appear. Then I would take that sentence and feed it into the voice already on the page. Even a little strand like that could totally reroute where I was going and was a nice way to germinate the text of the book outside my own world. It was magical and maybe terrifying at times to see how much of what we know about what those people did appeared right there in the words they are known to have said, without any action applied to it at all.

There are so many layers of voice to the story. It starts off fairly clear, with text ostensibly from Gravey's notebook, followed by Detective Flood's footnotes, but those voices devolve more and more as the book continues until we're almost guessing at who is speaking-Gravey, Flood, Darrel, Flood's dead wife, you, or even ourselves-and I wonder if you always had a clear idea who you were writing. Or, perhaps, if the primary motive was just to get down the story and the propulsion and the emotion, and it didn't matter as much who was telling it.

As the narrative continues, the voices do become more and more alike, which is somewhat a function of the plot-in that literally people are killing each other in such number that the perspective of the world itself becomes condensed. In the end, there is just one voice, which could be almost any person's voice, and thereby is capable of moving through all the perspectives fluidly, which is kind of how I imagine a world beyond death. Maybe even more than getting the story down, it's a result of an attempt to transcend the construct of place or time, or even of the human, into a state that is larger than a story, and is maybe more like drugs, in that it spans a space between our present reality and the reality of some day in which everything we know or remember has been obliterated, and where we are is somewhere else.

You've rarely given characters proper names in your previous work, more often using their roles as names, e.g. "the son," "the mother." But the names in 300,000,000 feel quite significant, in an almost deeply religious way (You write, "Why Darrel, I said, what is a Darrel, why not another name"). Why is it important for these characters, even the minor ones, to have proper names?

In that I knew everyone who appears in the book was going to be killed at some point, it was important to give them names. Names of the dead take on a significance that feels much different than who they were when they were alive; so whereas in earlier books I liked the universality of referring to the female protagonist as "the mother," because everyone has a mother and thinks of a mother in their own emotional way, here I wanted to enact the death of Officer Rob Blount, for instance. As for Darrel, who in the book serves as a kind of god figure, I thought about him the way I think about BOB in Twin Peaks; I don't exactly know what BOB is, or even fully what he represents, but I know in that world his name is terrifying, kind of like a password to terror, and I wanted this book to be filled with passwords, even if I am not sure even still what they unlock.

GOD = Gravey Or Darrel. Discuss.

I try not to speculate in my own life too much on what God could be. To me, it must be a presence beyond the human; I don't understand people who believe they should have a relationship with God as flesh, it seems presumptuous to me, even belittling. I am not very religious, but I do have big ideals. Gravey and Darrel in this book both exhibit elements of what I believe some omnipotent force could be; Darrel as the all-encompassing embodiment of a will outside our understanding, even physics, and Gravey as a tool of that force, allowed to interact between the spheres of life and death. Even my head gets spinning trying to sort it all out, but I love your code here, because I think every word or name can be opened when approached with the intent to see outside reality.

How do you feel about the word "sternum"? Your repeated use of it in 300,000,000 stuck out to me.

Sternum is a great word for someone's chest. It sounds like the ledge of something else, as if you could open yourself and crawl down inside a secret passage to somewhere you were carrying around all this time.

I was watching The X-Files recently, and a character said something that instantly made me think of your book: "Neither innocence nor vigilance may be protection against the howling heart of evil." Gravey's evil is the apocalyptic pandemic, but why? What makes the populace so susceptible to him?

I guess I've always imagined that all people were capable of evil, or at least capable of carrying it, though by culture and environment and morals we teach ourselves to behave, which begets survival of the species. "Capable of evil" doesn't even have to mean that you want to hurt or kill others-I certainly don't, as a person-but minds are made of cells, and cells can be colonized, and altered. While I was writing this book I was spending a lot of time around my father, who had Alzheimer's, and I think watching his persona change as a result of what was being done to his flesh and memory really had a pronounced effect on me in looking at what exactly a person is. It was one of the sources of daily anger that fueled the rage the book opens. Only over time, as I changed and the book changed, could I begin to see actual hope in it, despite itself; something beyond death, after the flesh has failed.

Besides 2666, were there other works-literary or otherwise-that informed or influenced the book?

Pierre Guyotat's Tomb for 500,000 Soldiers is probably the most immediate influence, as I read that for the first time right around the same time I began the book, and his language is infectious, as is the breadth of monstrosity he was capable of depicting. Also, certainly Dennis Cooper, particularly the orchestration of voice in The Marbled Swarm, and the voices of the youth in The Sluts. And, again, David Koresh and David Lynch. And Aase Berg.

The book slowly nears a close, we can sense it coming even without the physical knowledge of the pages running out, but how did you know that the story was finished?

I couldn't go any further.

And, of course, the final question: What are you working on now?

I am trying to be calm.

Buy Three Hundred Million: A Novel on Amazon

Get Three Hundred Million: A Novel on your Kindle