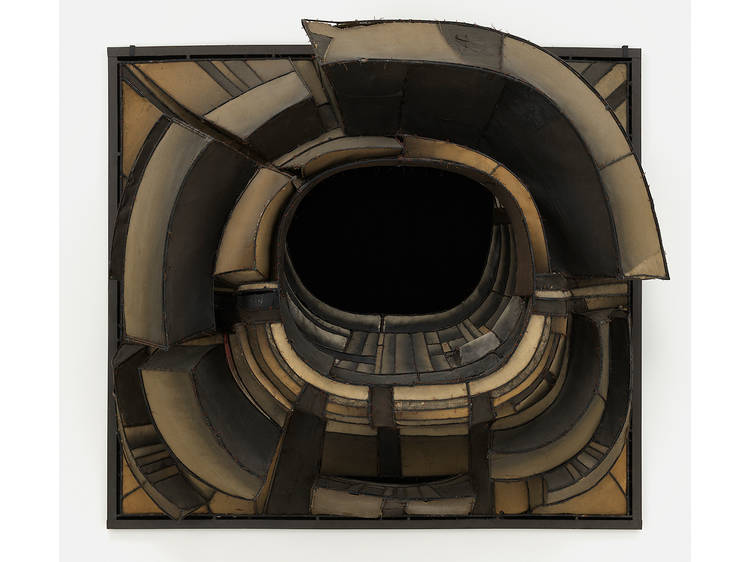

1. Lee Bontecou, Untitled (1961)

In the macho scene of postwar American art, Bontecou was a rare female presence, but when it came to making tough work, she could keep up with the boys and then some. This piece is made with industrial canvas salvaged from a conveyor belt that had been tossed out on the street by a laundry located below the artist's East Village apartment. The glowering form—suggesting a wormhole into some dimension of Cold War terror, or an eyepiece from a gas mask—was achieved by stretching fabric across a steel frame.