Ten years after he first emerged on the art scene, Joe Bradley (born 1975) is verging on middle age and the midpoint of a career that’s risen as rapidly as a bag of microwave popcorn. His painting technique has undergone several speedy stylistic change-ups to match, morphing from geometric, eight-byte stick men created out of stacked-together canvases in different uniform hues; to more naturalistically rendered silhouettes of figures against empty backdrops; to, most recently, a blend of abstraction and figuration.

The last might be described as grunge revivalism—smudgy, coarse and expressionistic, yet throbbing with a minimalist bassline as it skirts the border between sophistication and naïveté. Bradley’s art evinces an undeniable brio, recalling the jouissance of a five-year-old attacking the kitchen wall with a Crayola.

He’s quite good at what he does, in other words, if somewhat overrated. That’s only natural, given the art market’s ardor for fresh young talent. The trick is getting the short-term crush to translate into long-term commitment, and though Bradley isn’t quite there yet, his current offerings show him headed in the right direction.

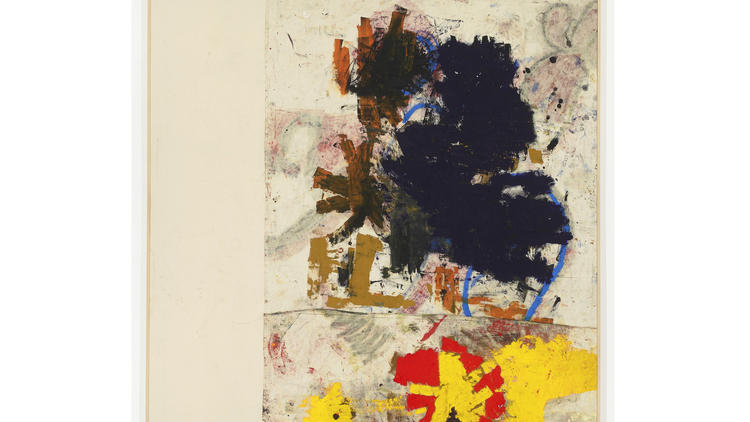

Here, he restricts the faux-naïf doodling that figured so much in his previous outing at GBE to a series of drawings, while leaving his paintings almost purely abstract. The front room, for instance, is guarded by a suite of four canvases (all titled Muggles, numbering two through five) that wouldn’t have looked out of place at the Martha Jackson Gallery in the 1950s. In Muggles 3, blocky passages of black, white, burnt orange, taupe and claret color float within the center of an otherwise raw canvas, whose edges are veritably frottaged with studio-floor refuse: shoe prints, marks left (presumably) by paint-soaked rags, clots of hardened pigment and other flotsam. There are creases running through the composition, suggesting that the work was folded at some point before it was completely dry.

This background treatment is foregrounded in the next gallery, where the pieces are shoddily stitched together out of separate rectangles of cloth, some of which have been left blank or gessoed white. This gives some of the works a strange stuttering effect, as if the paintings couldn’t quite get their message out. There are also bits of recognizable imagery here and there: a noodling spiral in one composition, a brown star in another and a series of polka dots within several, if you count such things as imagery. Overall, these works possess a quiltlike quality, which you might chalk up to the fact that the artist, like Poland Spring, comes from Maine—the North’s analog to Appalachia, and a repository of deep-in-the-bones folksiness.

You’d be barking up the wrong tree, however. We are very much in the realm of air quotes with respect to the issues at hand: “style,” “painting,” “quality” and, above all, “meaning,” the pursuit of which must seem patently ludicrous to an artist of Bradley’s generation.

This is especially evident in the drawings, which are arranged in an expansive grid of objects framed in light-colored wood. Disparate and rendered mostly in quick, cartoonish slashes of charcoal, colored pencil or Conté crayon, they run the gamut from a stoned-looking cat to the outline of a guy walking like an Egyptian. There’s something glyphlike about them all, but Bradley doesn’t appear to be offering us some lexicon of private symbols; rather, he’s giving us a ghost of symbology itself, absent any Rosetta stone.

It’s a form of nihilism that circles back to the paintings at the beginning of the show. Despite their evocation of New York School angst, or the very obvious (one might say too obvious) presence of the artist’s hand, they don’t really connect to anything beyond their own making. It’s not formalism or process art, exactly, but again, a deliberate elision of signification as an end in itself.

Ordinarily, something like that would bug me, but Bradley makes the act of painting himself into a blind alley riveting—he is that skilled. What would be even more fascinating, though, is to watch him get past the wink and the nod, to try and genuinely move us, if he gives a shit. And that remains a really big if.—Howard Halle