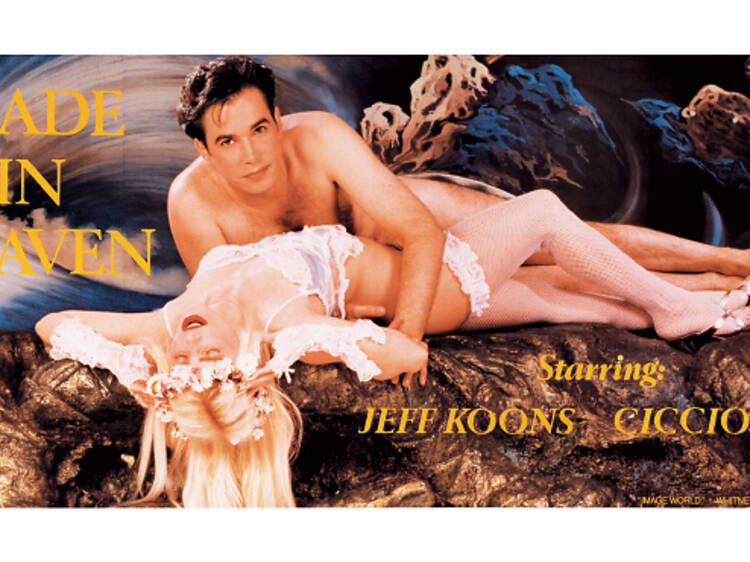

Jeff Koons, Made in Heaven, 1989

Would you say art has defined your life?

From the time I was a child, I developed a sense of self through art, and it’s been a way of not only having a form of self-identity but a connection to the outside world—a community outside of myself.

What interests you primarily?

Finding the path to enlightenment, to be able to fulfill yourself and to achieve the maximum vastness that you’re capable of reaching in life. To experience sensations, feelings, touch and excitement, while at the same time developing the intellectual capacity for abstract thought necessary to embrace the freedom that we have in this world for gesture and comprehension.

Your breakthrough series consisted of vacuum cleaners sealed inside of lit Plexiglas cases. What did they represent to you?

My aim was to add to the Duchamp’s legacy of the readymade, of course, but also to note that, while an individual’s integrity is revealed over the course of a life, objects possess integrity from birth. By not being used, by not participating in life, these objects are able to sustain an eternal state of newness.

Your work has always seemed particularly drawn to the notion that objects are defined by their presentation or display. Why?

It came from my childhood. My father was an interior decorator who had a furniture store. and it always seemed to me that the objects in the store or in our home were displayed for their own sense of being.

Another thing always associated with your work is the use of stainless steel or other reflective materials in pieces such as your inflatable-toy sculptures Rabbit and Balloon Dog, both of which have become contemporary art icons. What motivates your fascination with mirrored surfaces?

It’s about affirmation. A reflective surface tells the viewer that he’s important and lets him know where he’s at in the moment and in the vastness of the universe.

By the same token, why are you so interested inflatable toys and balloons?

I’ve always liked them for their anthropomorphic quality. We’re inflatables, after all. When we take a deep breath, we inflate and are full of life’s energy and optimism. Exhaling, we deflate, symbolizing our last breath in death.

The Whitney is apparently not shying away from showing some of the works from your most controversial series, “Made in Heaven,” in which you are seen having explicit sex with your former wife, the porn star Cicciolina. How do you feel about exhibiting that work again?

I’m thrilled to do it. To me, incorporating Cicciolina always represented a kind of readymade.

Why does sexuality seem to so often permeate your work?

It’s about self-acceptance. One of the first things that people have to overcome to achieve self-acceptance is their relationship to their own sexuality.

You’ve mentioned the word “acceptance” a few times so far in describing your work. What do you mean exactly?

There was a consciousness, even early on, about accepting my own experience as being valid. I didn’t need anything that I didn’t experience myself. I started to articulate these beliefs more directly in my “Banality” series. which is about the acceptance of your own cultural history. My recent “Gazing Ball” series also deals with the idea of acceptance through something people use as a lawn ornament—an object that can take you from the joy of affirmation to Platonic notions of pure form to absolute eternity.

That sounds pretty philosophical. Do you read much philosophy?

Philosophy has always been important to me, and I’ve studied some of the classics—Plato, Kierkegaard, Sartre and Nietzsche. But I mostly I believe in everyday interactions: remaining open minded, keeping everything in play and reacting to things that have relevance to me.

You have a very large studio with a lot of people working in it. How much are you still involved in the actual production of your work?

The work is a total gesture from me. It doesn’t exist without my articulation of it. I’ve created systems so that things can come into existence and go from concept to execution, while staying true to my original vision.

You once said that art has the power to astound and inspire. Do you still believe that?

I think art is life changing! I experience it everyday. If I come across a great work of art and I can trust in it and get lost in it, then it can really change my life.

How do you feel about being the last exhibition in the Whitney’s Marcel Breuer building on Madison Avenue?

I’m really honored. Scott Rothkopf, the exhibition curator, has tremendous insight into my work and brings a shared vision and scholarly point of view to the show. And their shows there have had a big impact on me.

And what about becoming the living artist whose works fetch the highest prices in the world? How do you feel about that?

I don’t think about it. Then again, I’ve always wanted to have a platform for my work; I’ve always wanted to participate. If you compare life to playing basketball, I’ve always wanted the ball so that I could go for the lay-up. But that’s the only meaning success has for me. The excitement that I have about waking up and going about my work comes from an engagement with life, art and family; it doesn’t come from any form of economics.

See the exhibtion

Discover Time Out original video