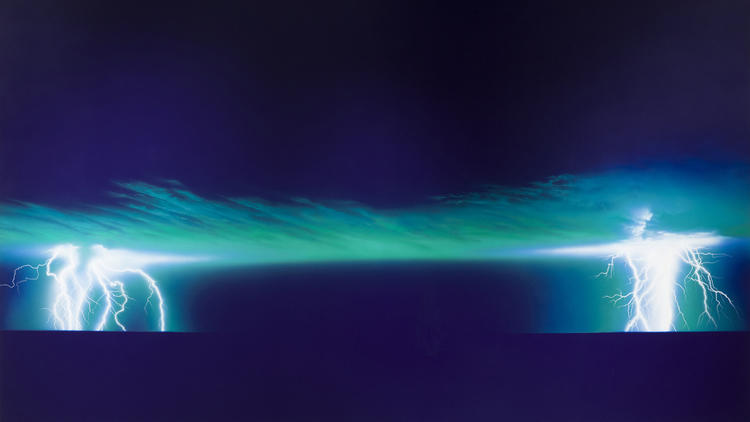

In the 1980s, Jack Goldstein’s Photorealist paintings of lightning storms and other luminous phenomena made an indelible impression. Copied from found photographs and impeccably airbrushed by assistants, Goldstein’s images of spectacular, ephemeral events (usually against night skies) form the center of this compact yet fascinating survey. These untitled paintings—such as one dated 1983, featuring a stark horizon under green clouds being struck by knots of forked lightning at opposite ends of the canvas—were among the most provocatively beautiful of their time, a period when beauty itself was suspect as a tool of patriarchal repression. But, untouched by the artist’s hand, they seemed equally challenging as illustrations of the “death of the author,” philosopher Roland Barthes’s influential idea that literary texts were cultural constructs rather than transparent instantiations of a writer’s intention and biography.

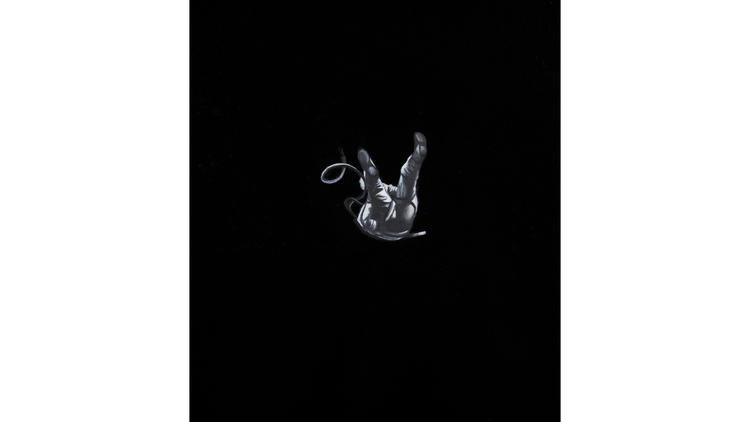

As this may suggest, Goldstein was a charter member of the “Pictures Generation,” a group of artists interested in appropriating images from popular culture for deconstructive purposes. Like several of them, he studied at CalArts under John Baldessari. He made forays into Minimalist sculpture and performance art, but a series of short films from the mid-1970s led to his inclusion in curator Douglas Crimp’s defining Artists Space exhibition, “Pictures,” in 1977. Produced by hired Hollywood professionals, these works sometimes took other moving images as their starting points. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1975), for example, comprises a three-minute sequence of the MGM lion roaring over and over again in a stuttering loop, announcing a movie that never begins. Others stage slightly dopey, unassuming events and infuse them with pregnant hints of story lines. In The Knife (1975), an ordinary table utensil changes color and emotional tenor as, one by one, monochromatic lights play over its surface, starting with a suspenseful bloody red. Art like this, or the artist’s vinyl records composed from stock sound effects, appeared to take apart and examine the workings of movies and narrative structures in order to defuse their power. In The Jump, a 1978 film that opens the exhibition, glittering lights fill the isolated silhouette of a diver in motion (taken, it turns out, from Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi epic Olympia), not only creating an enigmatic fragment of transient, if faintly sinister, grace, but also pointing the way to Goldstein’s paintings.

His canvases, however, never achieved the critical traction of his films, not even when they appropriated familiar icons, like a 1981 composition that faithfully reproduces Margaret Bourke-White’s WWII photo of the bombing of Moscow, the starry sky lit up by flares and rocket trails. In the end, the work was still painting, which starchy academics had declared dead, a moribund zombie that refused to lie down. These days, Goldstein’s flawless rendering of fleeting moments captured by photography—often blown up to a cinematic scale—seems entirely up-to-date, a genre-bending essay on how representation operates, and why paintings still possess a compelling magic different from that of other kinds of images. Think of the work of Richard Phillips, say, or Marilyn Minter.

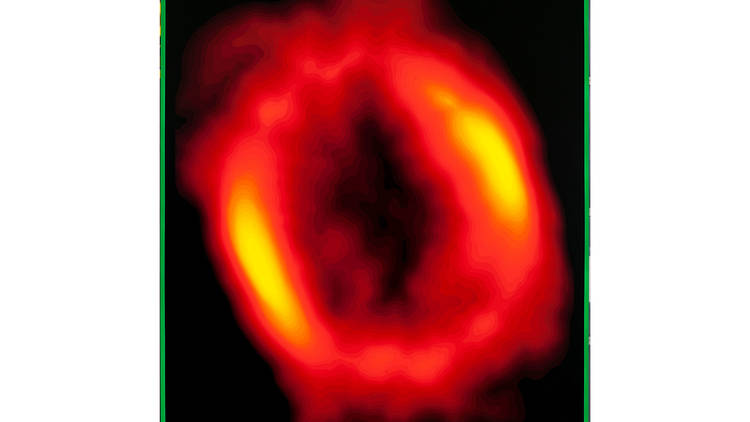

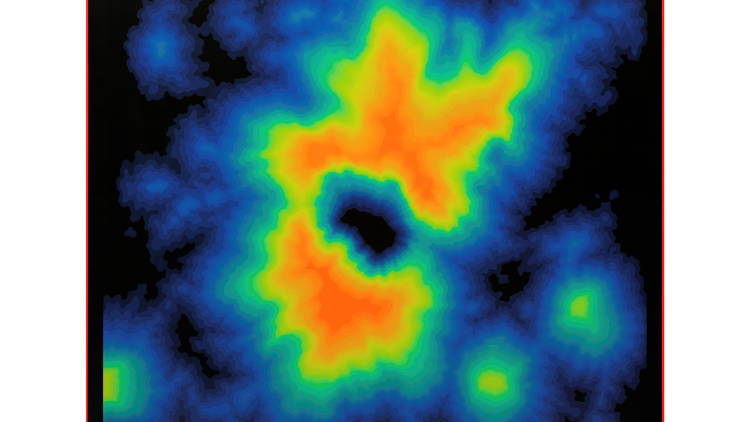

Goldstein’s paintings from the late 1980s abandoned photographic sources in favor of computer-generated thermal imaging, looking like intensely hued topographic maps. Despite their seductively baleful glow, critics at the time misinterpreted them as Neo-Geo abstractions. Now they appear prescient, predicting our culture of surveillance, Google Earth and digital scans.

Frustrated, broke and addicted to heroin, Goldstein disappeared from the art world in the 1990s, living in a trailer on the outskirts of Los Angeles, ultimately killing himself in 2003. He completed a final film, Under Water Sea Fantasy (1983–2003), by manipulating the color of nature-documentary footage. The subjects—an erupting volcano, sun-dappled coral reefs, a lunar eclipse—recall his paintings. Sadly, while the effects prove captivating, they hardly make for the trenchant analysis of his earlier work.

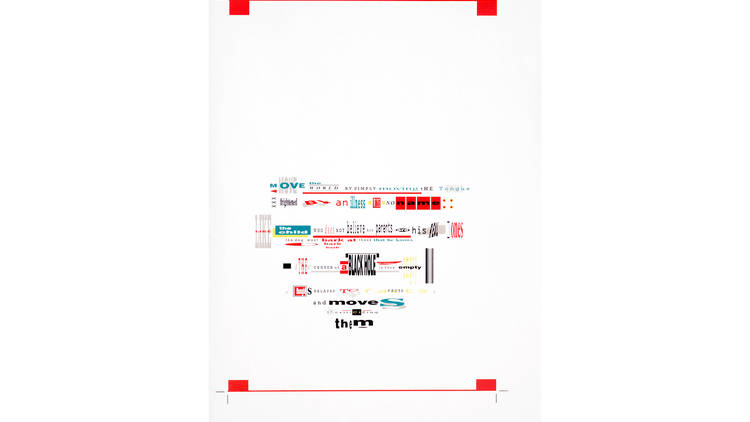

In fact, Goldstein seems to have spent much of his last decade working on the 17 photocopied volumes of his Selected Writings (2002), a strange, hermetic collection of phrases and sentences copied from the philosophy books that he avidly read backward. Although it resembles nearly nonsensical concrete poetry, he thought of it as his autobiography. Selected Writings lacks an authentic authorial voice; it speaks in multiple tongues, evoking the “ten thousand Jack Goldsteins” the artist claimed were in any phone book (a notion that lends this exhibition its title). A pioneer of appropriation, Goldstein erased his presence as much as possible from his work, so maybe, as John Kelsey suggests in the show’s catalog, this concluding act of polyphonic ventriloquism really is his true story.—Joseph R. Wolin