From the Five Boroughs to the Finger Lakes, we ranked the top sculpture gardens for outdoor art and exhibitions

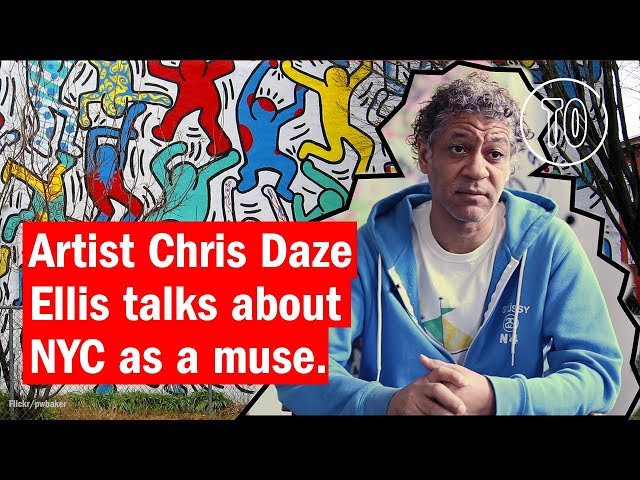

A pioneer of New York’s graffiti scene during the chaotic years of the 1970s and ’80s, Chris “Daze” Ellis is one of the few artists who made the leap from the subways and streets to the international art world. Over the past four decades, he’s exhibited his work at numerous galleries, both in New York and worldwide, while his paintings have been collected by such major art museums as MoMA. Even so, he’s continued to create street art murals along with more traditional canvases like the ones making up his current show at P.P.O.W. Gallery in Chelsea. Tilted “Daily Commute,” the exhibit captures the spirit of New York with vibrant scenes of Midtown, Times Square, Brooklyn and Jackson Heights in Queens. Time Out New York recently sat down with the artist at his South Bronx studio, where he talked about his current work, and his legendary graffiti career back in the day.

How old were you when you first started painting graffiti on subway trains?

It was back in 1976, so I must have been 15 or 16 years old. I didn’t consider myself to be an artist at the time, but I knew that I was doing something creative.

What compelled you to do graffiti?

Well, that same year I got into the High School of Art and Design and started meeting people who were doing it. There was a moment when I saw a train pulling into a station with cartoon characters from Mad Magazine on it and that’s when I knew I had to be part of the scene.

Did you work at night, in the tunnels?

I worked in all different kinds of conditions—nighttime, daytime, summer, winter—everywhere.

Did you ever feel like you were in danger?

When you’re a teenager, you don’t think too much about stuff like that. It was more about the thrill of doing it, but in hindsight I realize that some of the things I did were pretty crazy.

Were you ever arrested?

Luckily no, but I knew plenty of people who were.

What made you decide to stop working on the subways?

I felt that I’d hit all of my personal goals. I’d already been showing in galleries for a couple of years by the time I stopped painting trains, which was about 1983 or ’84. The whole aspect of subway graffiti was changing. A new generation was coming in and I thought that I should pass the baton on to them.

Your first solo show was in 1982 at a gallery called Fashion Moda in the Bronx, not far from here. How did that happen?

I’d been painting subway cars in The Bronx for some time and I heard about the place and knew that’s where I wanted to be. There was an art scene going on there, even if it wasn’t being covered in the press. Crash [another graffiti artist] and I pooled our money to rent a studio together in the South Bronx and eventually, Fashion Moda saw what I was up to and offered me a show.

Photograph: Joshua Aronson

Speaking of the press, back then, the papers were practically describing the South Bronx as hell on earth. Was it as bad as all that?

Look, the South Bronx had been dealing with crime and poverty for a long time. But the press—and we’re really talking about the white press here—seized upon the most sensationalistic aspects of what was going on. Those of us who were there knew there were positive things happening, like the rise of hip-hop culture, which also included graffiti.

In 1982, you collaborated with Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf and several other graffiti artists to make a mural for what’s now called the Houston Bowery Wall. Was there camaraderie between you guys, or was it more like a rivalry?

You might call it a friendly rivalry. The wall mural came about because of discussions between Kenny and I about working together, and he came up with the idea of painting the wall, which is still being used for street art today. Of course, what we were doing was illegal at the time.

Has the city always been the subject for your work or was that something you settled on later?

I’ve used urban imagery since the beginning, but I only began working in series during the late-’80s. My first series explored Coney Island, a place that has always resonated with me since my family took trips out there when I was a kid. It’s a distinct part of the city and had historically been painted by Reginald Marsh and John Sloan.

What determines your choice of neighborhoods or scenes?

I want to reflect the character of the city. After the Coney Island series, I did one on elevated subway stations, which was interesting because some of trains rolling by had my work on them. But I also try to tackle diversity. There’s a painting in the show titled Jackson Heights, which is one of the most culturally diverse areas of the city. I’m against the current xenophobic atmosphere.

You mentioned Reginald Marsh and John Sloan. Who are some of the other artists who’ve influenced you?

I’ve always been a fan of black and white photography by people like Weegee, Bernice Abbott and William Klein. In fact there’s some black and white elements to couple of paintings in this show, which may have been partially inspired by them. I was thinking about how people mention color more than content when talking about graffiti. So I thought that if I took the color out, they could focus on the content.

One recent painting in your show is called Generations, and it catalogs the graffiti tags, style and statements spanning your lifetime. What’s the story behind that canvas?

Well, it’s an interior of a subway car from 1976 with graffiti tags from artists of the period taking the upper portion of the composition. The lower part has contemporary graffiti, with protest phrases like “Fuck Trump” and “The Informed vs. The Uniformed,” which is where I think we are today.

Who are your favorite contemporary street artists?

I really like Swoon’s work and Os Gemeos, whom I’ve collaborated with many times. I also enjoy Shepard Fairey’s work and just saw his documentary. They’re all younger than me, but I really appreciate what they do.

You and your peers basically started the worldwide movement in street art. Do you ever think about your legacy?

Not really. I prefer to look forward, not back. I’ve been told that my work has been inspirational to people, and I certainly take a lot of pride in that.

Photograph: Joshua Aronson

Chris “Daze” Ellis, “Daily Commute” is at P.P.O.W. Gallery through Mar 17.