Working together for nearly 50 years, Gilbert & George have consistently been at the forefront of British art. Starting out as “living sculpture,” they evolved into fearless picture makers, willing to tackle a broad range of controversial subjects. For its exhibition “Gilbert & George: The Early Years,” MoMA draws from its extensive collection of works by the duo created between 1969 and 1976. Below, they discuss their sometimes scatological, often whimsical efforts, as well as their half-century of collaboration.

What’s the idea behind being Living Sculpture?

There is no “idea” behind our Living Sculpture, but there is much “within” it. It is us alive in front of the world each day with all the thoughts and feelings that lie within all human beings.

Why did you often depict yourselves in the early years in pastoral scenes?

Simply because we are both “country boys” and we had yet to find our way to be artists in a city.

What was your reason for making and mailing creative announcements and invites, which now make up a major portion of the MoMA exhibition?

We invented “Postal Sculptures” because we had no access to gallery or museum spaces. But we still wanted to speak as artists. The “Postal Sculptures” short-circuited the art world—going through letter boxes directly to the human living space. They were an enormous success, and we had an amazing response from all over the world.

Who was on your mailing list?

Our mailing list came from the late Konrad Fischer and Anthony Matthew of Editions Electra.

Why did you mail out the eight cards from The Limericks, Pink Elephants and The Red Boxers series over eight weeks?

The “Postal Sculptures” were sometime in a series of eight, as we wanted time to create an ongoing emotional relationship with our recipient.

Did you see your early work as being conceptual art, mail art or performance art, or do you reject all of those categories?

Our art is not part of any particular movement. Rather it is a human, democratic 20th- to 21st-century relationship between our art and the viewer.

How did MoMA’s 1971 acquisition of your charcoal on paper sculpture To Be With Art Is All We Ask… impact your career at the time?

We, as baby artists, were of course thrilled to place To Be With Art Is All We Ask in such an important museum.

Another one of your large charcoal on paper sculptures in the show, Bar #2, deals with drinking, which several other works of your works flirt with as well. Why boozing as a subject, and do you still indulge?

We created Drinking Sculpture and The Bar II in response to the institutionalized use of alcohol and its multitudinous aspects to create various states of being.

What was your reaction when the art publication Studio International censored your photograph George the Cunt and Gilbert the Shit, which you gave it as a magazine sculpture?

In 1971, the trendy internationally famous art magazine called Studio International censored two offending words in our first “Magazine Sculpture,” George the Cunt and Gilbert the Shit. We realized that we were on the right track. Our art has always been able to bring out the bigot from inside the liberal and conversely to bring out the liberal from inside the bigot!

What will we see in the three videos on view (Gordon’s Makes us Drunk, A Portrait of the Artists as Young Men and In the Bush), which you gave to MoMA back in 1998?

With the late Gerry Schum’s Video Gallery, we created three Video Sculptures. Gordon’s Makes us Drunk deals with the ecstasy and intellectuality of legalized euphoria. Portrait of the Artists as Young Men deals of course with time (the duration of a lighted and smoked cigarette), mortality, morality and the ability to freeze thoughts and feeling with imagery moving. In the Bush shows the human person’s involvement and anxiety with our modern world—in and out in never-ending different ways, not unlike birds or animals, stopping, starting, hiding, swerving, slowing down, speeding up for all time.

The only work not credited to you in the show is a 1974 portrait of you at home by Cecil Beaton. What was it like to be photographed by Britain’s master portraitist of that time?

In 1974, we as Living Sculptures decided to commission various artists and photographers to create portraits. We thought that Cecil Beaton was very imaginative and very charming.

We’ve heard that MoMA is planning to release your first vinyl album of the song “Underneath the Arches” from The Singing Sculpture during the show. Why did you choose a song of homelessness as your anthem?

We did not choose the song “Underneath the Arches.” We were walking past a secondhand shop near Euston when we were drawn to enter where the gramaphone record seemed to “choose us.” Its words and music spoke to us of us. Like the tramps in the song, we had nothing but were not down-hearted.

Why do you think your model of working collaboratively spawned other artistic duos, such as McDermott & McGough, Pierre et Gilles and Doug and Mike Starn?

We are not “working collaboratively”! It is more simple—it's just that we are “Two People but One Artist.”

“Gilbert & George: The Early Years” is at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) through Sept 27.

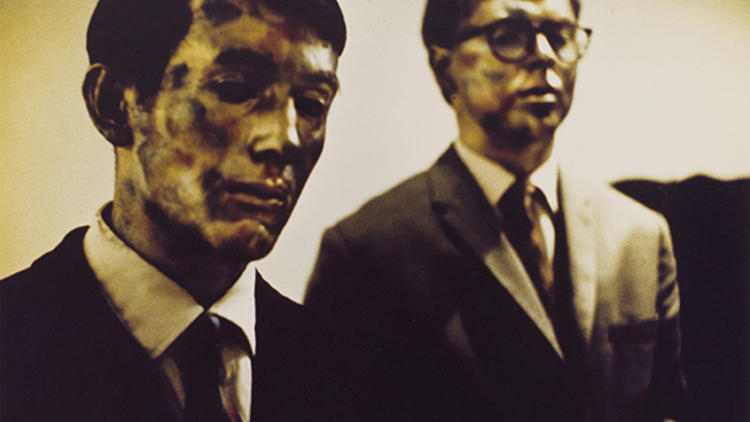

Gilbert and George at their home studio in East London

See the exhibition

Discover Time Out original video