If you’re interested in Frida Kahlo’s art, you may find this look at the Mexican artist wanting. On the other hand, if you’re primarily interested in Kahlo’s legend, “Appearances Can Be Deceiving” does an entertaining job of burnishing it, though maybe not as well as Kahlo (1907–1954) did herself.

Kahlo’s renown grew out of her knack for self-mythologizing, so perhaps it makes sense that this show begins with her name in billboard-size letters and concludes with a giant photomural of Kahlo, providing viewers with an Instagrammable moment as compensation for not being allowed to photograph the exhibition. Meanwhile, Kahlo’s paintings (mostly self-portraits, her default mode) take a backseat to archival photos and film footage, as well as personal items such as jewelry, pre-Columbian pottery and various types of cosmetics. The main attraction is a collection of the artist’s multihued dresses inspired by the Tehuana culture of Mexico’s Oaxaca region, where her mother was born. (Kahlo’s father was German.) The proceedings resemble something you’d see at the Met’s Costume Institute—indeed, I’m surprised they didn’t think of it first.

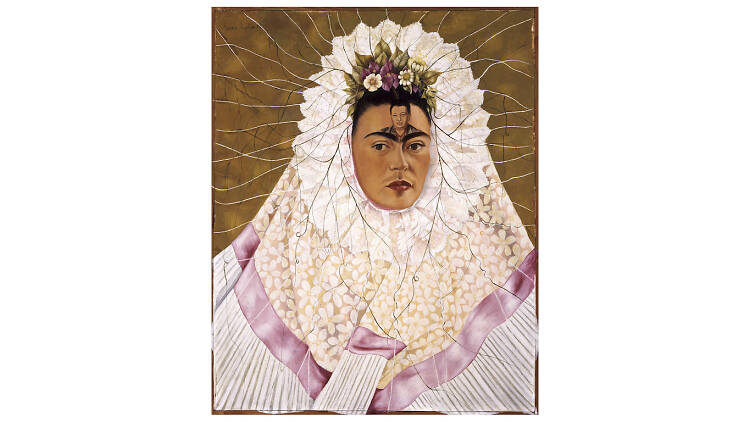

There wasn’t much daylight between Kahlo’s art and life, as the former was intertwined with two main events from the latter: a streetcar accident, which left her in a lifetime of pain from a crushed spinal column that forced her to wear corsets and leg braces, and a troubled union with Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. The couple married, divorced and remarried; stranded in a class-A state of codependency, Kahlo had affairs with both men and women while her husband indulged in serial philandering. (One of his mistresses was also Kahlo’s lover.) The yin and yang of their relationship is best represented here by two canvases: one, a Surrealistic fantasia depicting Kahlo as a cosmic earth mother cradling a baby Diego sporting his adult face; the other, a full-length self-portrait painted shortly after her separation from Rivera in which she’s seated, hair shorn, wearing her husband’s clothes. The true state of affairs, though, can be inferred from a photo of Kahlo at her easel, Rivera looming behind her: the great man of art history indulging his wife’s hobby.

Out of this emotionally parched soil sprang Kahlo’s status as a feminist icon and, thanks to her embrace of her mother’s mestiza heritage, as a pioneering artist of color. And who really thinks of Diego Rivera anymore? Certainly not the museumgoers snapping selfies in front of Kahlo’s image as they exit the show.