In his twenties, David Byrd (1926–2013) studied in New York with the French modernist Amédée Ozenfant; then in 1958, he moved to a small town upstate, where he painted assiduously, but unknown and alone, for nearly the rest of his life. Now, two august New York galleries—White Columns and Anton Kern—have joined forces for a major reintroduction of a gifted yet anachronistic artist.

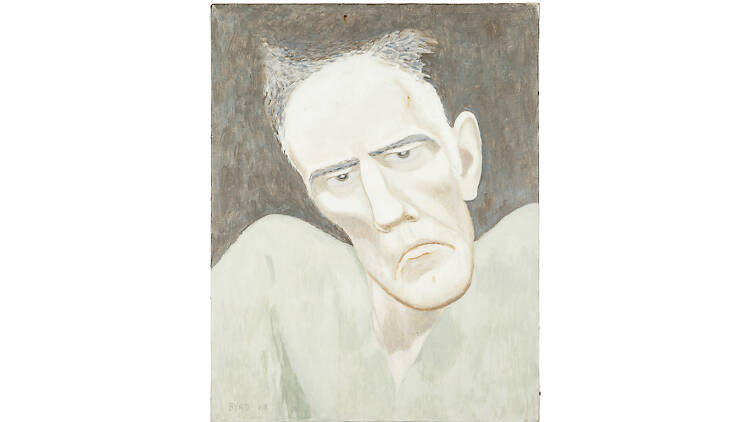

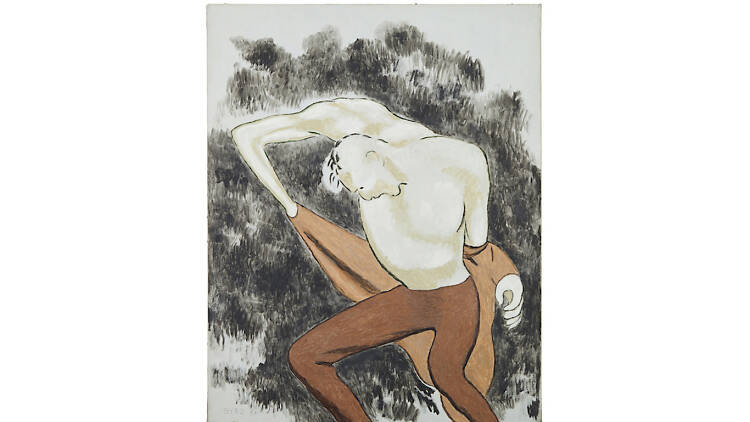

Byrd’s interest in the artistic developments of his own era seems to have ended sometime during his youth, and his work consistently harks back to older generations: Ozenfant’s stripped-down Cubism but, even more, American Regionalism and Social Realism (especially the humanistic concerns of Ben Shahn and Robert Gwathmey), as well as the bleak loneliness of Edward Hopper. Byrd’s palette, however—a sea of greige, chalky mint, rust, apricot and a sky blue that he seldom used for painting the sky—feels entirely his own, and its pale tonalities endow his subjects, no matter how pedestrian, with some of the gravity and tranquility of early Renaissance frescoes.

White Columns focuses on paintings Byrd made about his 30 years working as an orderly at the VA hospital in Montrose, New York. Images of the patients under his care often display a kind of natural surrealism, such as Putting on Top (1960), where a tank top obscures the head of a naked man, transforming him into an alien. Kern’s more eclectic selection includes landscapes and street scenes, but the most memorable pictures carefully observe the gestures of people going about everyday lives. The Kiss (2005) shows a mother doubling over to peck the upturned face of an orange-capped child—standing in, perhaps, for the human connections that fascinated Byrd but that, on the evidence here, he approached from a distance. Simultaneously insider and outsider, Byrd appears to have lived largely through his art.

Works by David Byrd are also on view at White Columns, through Mar 9