In anticipation of her first show since her contribution to the 2017 Whitney Biennial (a portrait of Emmett Till in his coffin, after he was lynched and mutilated by a mob for whistling at a white woman) ignited a firestorm of protest from African-American artists, Dana Schutz went on a kind of Kevin Hart-style non-apology tour, telling The New York Times that, yes, “It’s good those voices were heard,” and that, in any case, the task of “register[ing]” the “monstrous act” of Till’s death was probably always “impossible.” What she could have said, but didn’t, of course, was something like, “I stepped in doo-doo because I was blinded by white privilege.”

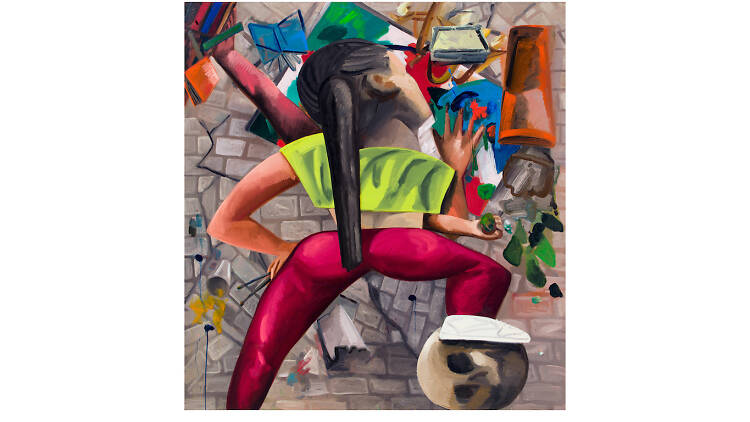

But that was then, and this is now, and the art world, after a perfunctory rending of garments, has moved on. Her latest work, which continues to follow her formula of whipping abstracted figuration to an Expressionistic froth, may or may not reflect directly on Schutz’s recent travails, though one canvas, Painting in an Earthquake, does seem to address the controversy by picturing the artist as she heroically continues to paint while her studio—shaken by unseen forces—crumbles around her. Self-aware it isn’t.

Admittedly, I’ve been somewhat more resistant to the charms of Schutz’s practice than the critics who are hailing her show as a triumphal return. Among the women painters of her generation—Nicole Eisenman, Amy Sillman, etc.—Schutz is the one I've never quite understood what it was she was after, aside from displaying her considerable skill with a brush. Her style is a busy compendium of tics borrowed from a host of art-historical giants, with a particular debt to Philip Guston. (Indeed, these works are her most Guston-y to date.) That’s hardly a federal crime, as plenty of contemporary painters are cashing checks that Guston wrote. The problem for Schutz is that, ultimately, for all the visual pizzazz she delivers, her work just seems like a formal exercise devoid of a raison d'être. That’s why Open Casket, as the Till painting was called, backfired so spectacularly: Schutz reduced the monstrous act she was so intent on telling the world about to an excuse for treating Till’s battered face as a playground for bravura brushwork.

Wisely, this exhibition, which includes sculpture, avoids anything as high-stakes, presenting instead a series of allegories of the artist struggling with or against…something. Injustice? Global capitalism? A bad hair day? Schutz practically hits you over the head with sturm und drang, the only question is, Why?

In Mountain Group, for instance, Schutz pictures herself on the eponymous peak, trying to limn an alpine scene. But her view is blocked by a gaggle of grotesque figures piled on top of each other as they cling to the summit and point their fingers in the air. In Treadmill, a woman whose head bears an odd resemblance to a trout’s lifts her chin to let out a scream as she exercises. Her expression recalls the one worn by the distraught mother in Guernica, which I assume is deliberate since Picasso is referenced throughout the show, including one painting in which a grumpy business traveller is confronted by an ectoplasmic female form that echoes one of the Barcelona whores from Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. What this adds up to is anyone’s guess, though it suggests that Schutz has a tendency to confuse first-world problems with genuine angst.

Schutz’s sculptures don’t really add or detract from the show and seem to exist mainly to prove that she can render form in three dimensions. The main attractions here continue to be her prowess with paint and her adeptness at rifling through the canonical closet. There are visual pleasures to be found, as long as you can overlook the fact that Schutz’s sound and fury doesn’t signify all that much.