Édouard Manet, Before the Mirror (Devant la glace), 1876

Édouard Manet, Before the Mirror (Devant la glace), 1876

Photograph: Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

A lot of New York art museums—the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art among them—have fabulous collections, but no NYC institution provides the kind of viewer experience that the Guggenheim does. The reason, of course, is Gugg’s Frank Lloyd Wright building, which leads visitors along the famous spiraling ramps of the museum’s rotunda. Unique as the building is, however, what ultimately matters is the art, and in that respect, the Guggenheim’s holdings, especially its masterpieces on canvas, deliver—as you’ll discover in our list of the best paintings at the Guggenheim

RECOMMENDED: A full guide to the Guggenheim New York

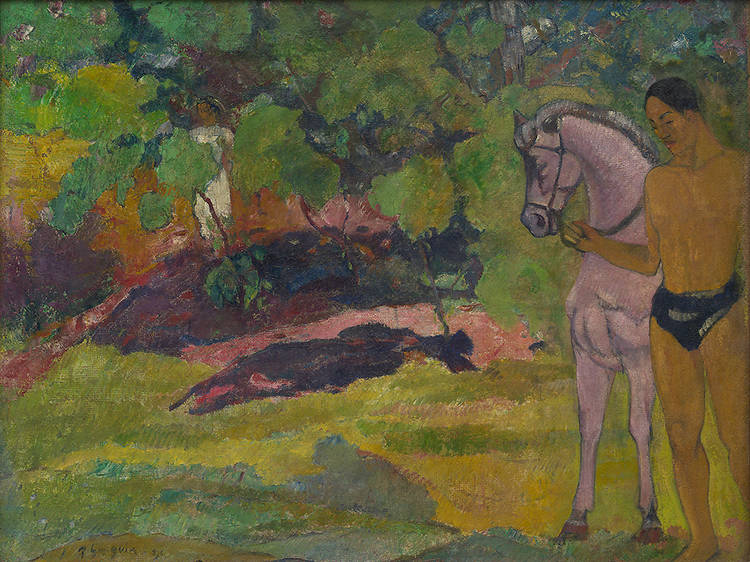

Gauguin, the former tarpaulin salesman and stockbroker who famously abandoned Europe and his family to live a supposedly pure and spiritual existence in Tahiti, was a progenitor of primitivism, which looked to non-Western cultures for inspiration. But not always: this painting derives in part from a classical source: The sculptural frieze on the Parthenon.

Paul Gauguin, In the Vanilla Grove, Man and Horse (Dans la vanillère, homme et cheval), 1891

Photograph: Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation/Kristopher McKay

While not as radical as Malevich’s later Suprematist compositions (like Black Square), Morning in the Village is arguably his most beautiful and sublime work. In this abstracted scene, a country hamlet stirs itself after a blizzard, its streets and rooftops blanketed by a purifying white that erupts in prismatic shards of blue and red touched with accents of yellow, black and grey. At once formal and hallucinogenic, it rivals the work of Bruegel as a panegyric to peasant life.

Kazimir Malevich, Morning in the Village after Snowstorm (Utro posle v'iugi v derevne), 1912

Photograph: Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation/Kristopher McKay

Bonnard was the odd man out of 20th-century art. Although a contemporary of Picasso, he made work that was considered a throwback to Impressionism. Bonnard based his canvases on heavily annotated drawings hastily scribbled on small scraps of paper. These weren’t studies so much as notes to himself, meant to jolt his recollection of a subject as he sat at his easel. Interiors like this one—created in years before his death in 1947, and mostly at the home in the South of France he shared with his wife, Marthe—are prime examples of his style. The results, lush and vibrantly colored paeans to bourgeois domesticity, also posses an otherworldly evanescence, describing a place where past and present collide, where ordinary things become extraordinary.

Pierre Bonnard, Dining Room on the Garden (Grande salle à manger sur le jardin), 1934–35

Photograph: Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

The subject of this painting is Marie-Thérèse Walter, who Picasso first met in 1927 when she was 17 and he was a married man of 45. She soon became his mistress and model, appearing frequently in his works during the following decade. Picasso was fond of depicting her while she slept, because he thought it captured her in her most vulnerable, intimate state. Here, she lays her head on her arm, which Picasso depicts as a fleshy, sensual extension of her flaxen locks.

Pablo Picasso, Woman with Yellow Hair (Femme aux cheveux jaunes), Paris, December 1931

Photograph: Kristopher McKay

Discover Time Out original video