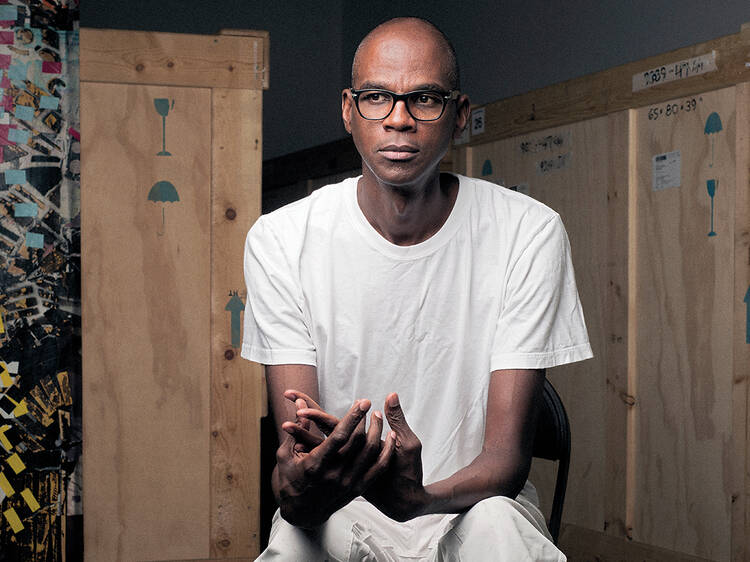

Born in 1961, Los Angeles artist Mark Bradford draws inspiration from two sources close to home: growing up in South Central L.A. during the ’60s and working in his mother’s hair salon. Bradford’s densely collaged, maplike abstractions have won him acclaim and frequent appearances in the biggest art galleries and museums in NYC, and he returns to the city this month for his inaugural show with megagallery Hauser & Wirth. Bradford still lives in his old neighborhood, and speaking from his studio there, recalls his transition from styling Jheri curls to creating social abstractions.

You’re known for unconventional materials, like permanent wave endpapers. Is this a reflection of working with your mom?

Absolutely. I’m a third-generation hairdresser, and those were the sort of materials lying around my mother’s shop; we used them for Jheri curls. They were translucent and could be layered like paint. And they were cheap, too, which was important for a grad student who wound up $150,000 in debt.

Wow. Speaking of which, you attended CalArts, which isn’t really known for producing abstract painters. How did going there affect you and your work?

Well, I never felt so black as when I went to school there. Before that, I just felt like Mark. But I read a lot about identity politics at CalArts, and once I finished my MFA, I knew I wanted to deal with race, gender and maybe sexuality and class. They felt like such big hot potatoes. But then I thought, How am I going to deal with this stuff, with the freedom to play around with it? That’s what led me to abstraction, but instead of the type that looks inward, like in the ’50s, I wanted my work to look outward at the world I lived in.

You call your work “social abstraction.” What does that mean specifically?

I’m fascinated by the fact that the Civil Rights movement took off concurrently with the development of abstraction in America. Jackson Pollock had been in Life just a few years before Emmett Till’s murder in Mississippi. So my work bounces between social issues and the history of abstract art. I’m not a spokesman for social issues, but I do have an interest. I try to keep one foot in art history and the other foot at the bus stop.

How is this expressed in the way you work and the materials you use? We talked about endpapers and other stuff that referred to your background. What else?

Well, as I mentioned before, I was using endpapers—which are actually tissue paper—but after a while I realized I needed something else, something that reflected the urban environment I live in. I was familiar with the work of Nouveaux Realist artists like Mimmo Rotella and Jacques Villeglé, who used billboard and street poster materials, and realized that same sort of detritus could be found on the streets of Los Angeles. So I began pulling down posters around town, but so many of them had been layered on top of one another that I had to soak them in water to separate and save them. And by doing that, I no longer thought of it as paper but as paint trapped in a binder. That’s all that stuff really is: pigment and pulp. So rather than using the posters like you would in a collage, I use it like paint.

It’s interesting how you connect material to place, because some of those advertising posters you use are directed at a very localized consumer. I refer to one of the new works in the show, Reduce or Erase Your Criminal Record, which I’m guessing came from an ad touting some sort of legal service.

Yes, I describe those kinds of businesses as “parasitic” merchants. They prey on the vulnerable: We know you’re in trouble; we know you take the bus; we know you’re losing your house, etc. I think they must do as much market research as Apple! These guys know their demographic, and their posters tell you exactly what’s going on in that community right now. And they’re designed like there’s always an emergency—911, 411, 311. It’s always red light, red light!, with all of these action colors and graphics. And what attracted me to the REDUCE OR ERASE YOUR CRIMINAL RECORD poster was knowing that it could never deliver on its promise. But more importantly, it brought up the whole idea of young men being incarcerated, which is a huge topic now. And here was evidence of it—right on a telephone pole!

As much as your work has a certain physical presence, I don’t think I can recall seeing anything as sculptural as the hanging piece, Waterfall. Have you done anything like it before?

No, which never stops me. It grew out of another piece, a 100-foot-long wall work. I thought about the wall as a space and spent a lot of time experimenting. I was playing around with some ropes, and one wound up draped over something else, which got me thinking about how most people think of a painting: as a rectangle on so wall. So I decided to make a three-dimensional painting that doesn’t have a frame around it. It’s the same fragments of paper, just less formal. It’s part sculpture, part painting—an in-between thing. I’m sure I’ll make more of them.

Your new work also includes these paintings—Killing the Goodbye, Cigarettes and Bubblegum—that almost seem mutilated. The have a tone that’s distinct from your other paintings. What led you to making them?

They came out of taking images of AIDS cells and turning them into marks for paintings. I was laying down all of these dots and began to wonder what would happen if I started to cut them out. We often use military expressions when speaking about the body—like the “war on cancer.” The idea of the body already seemed to have floated into these works, so lacerating them made a kind of sense. I discovered a different type of line and way to reveal layers.

The AIDS theme seems especially noticeable in the videos you’ve put in the show. There’s one called “Spiderman,” which is about the black community’s experience with AIDS, in which you’re doing an over-the-top stand-up act. How did you come up with that?

I’ve always been interested “party” records from the ’50s and ’60s—that Redd Foxx sort of humor. So I wanted to do a monologue that sounded like that but about a serious subject. The piece is funny but very dark, because the AIDS crisis was a dark period.

And what about the other one, “Deimos,” which seems to be set in an old roller disco. Is that a reference to the old Roxy club that used to occupy the building Hauser & Wirth is in now?

Oh, yes, honey, yes! This piece shows the end of the party; everyone’s left, and there are all these roller skates drifting around. I’m abstracting the history of the place while trying to evoke what it was like. The video plays with the site and materiality. I spent a lot of time in nightclubs growing up; I have a Ph.D. in nightclubs. So, nightclubs, drag queens—yeah, sign me up!

See the exhibition

Discover Time Out original video