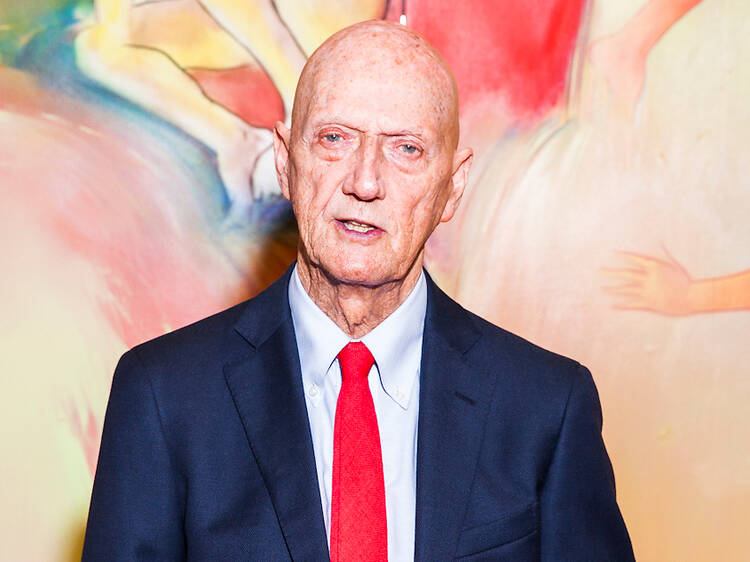

One of Britain’s most celebrated Pop artists, Allen Jones is known worldwide for his controversial 1969 sculptures Hatstand, Table and Chair, which morphed women in bondage gear into the eponymous pieces of furniture. While those works aren’t in Jones’s first major New York art show in nearly 30 years, plenty of prime examples of his provocative paintings and sculptures are. Standing among them at Michael Werner Gallery, the 78-year-old artist weighs in on Pop Art’s legacy and being a target of feminist critics.

How did you get into Pop Art?

When I was a student, abstraction represented the main thing, but I couldn’t abandon representation. I became attracted to Pop Art because it wasn’t a movement with a manifesto; it was a kind of spontaneous eruption in both New York and London.

Why do you think it’s had such a lasting impact?

Because it represented entirely new subject matter, which was consumer society, and it was about real things. Pop Art provided images that people could relate to.

Is it true that your best-known works, Hatstand, Table and Chair, were inspired by seeing a slot machine shaped like a showgirl on a trip to Reno?

Yes, but it was about five years prior to making those pieces. Once I began to make them, I realized they were related. Here was a representation that was very direct, like a cigar-store Indian. It had no artistic pretension, but it had real net stockings and maybe a wig. Most interestingly, it looked like a chainsaw had taken out a whole section of the figure to make room for the slot machine, which you stood in front of and cranked after putting your money in. The whole thing was a poetic idea of sex or desirability; you cranked away with the hope of a payoff. It was such a wonderfully strong and playful image.

Yes, but when you first showed those works, they provoked outrage and still do today. How do you feel about being labeled a misogynist for making them?

The problem wasn’t what I did but how, by representing the figure realistically in fiberglass, without any pretense of making fine art.

So it was your choice of medium that caused the fuss?

Not entirely. I’d originally put street clothes on the figures, but once I did, they just looked like Surrealist found objects. I realized that drawing on an American comic-book idea of the figure was again a way of undermining fine art. I also thought the idea of making the figure into a table or a chair was kind of a hoot. I wanted to offend the artistic canon, but it just so happened that these works were exhibited at the moment when feminism was on the rise.

Right, but how did you address that?

Well, there wasn’t much I could do about it. For the next 10 years, whatever I said sounded like an apology.

Yet after all of that, you still use the female figure in similar ways.

It’s compulsive. I would love to paint squares, but that’s not my thing.

“Allen Jones: A Retrospective” is at Michael Werner Gallery, through June 4.

Check out the best free art in NYC

Discover Time Out original video