When Dave Eggers named his fictionalised biography A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, he was either delivering a shot across the bow of American literature or poking fun at the bubble reputation. He could even have been doing both. It’s in the same vein that Kim Ho names his new work The Great Australian Play. It’s both a laying claim and a total piss-take.

The idea of the Great Australian Play hasn’t got as much of a psychological pull as the idea of the Great American Novel, and fewer claimants to the title. Maybe Ray Lawler’s Summer of the Seventeenth Doll remains the frontrunner, although Ho is clearly sweating under the influence of Patrick White, who not only gets several mentions, he gets his own cameo.

Ho draws most directly from White’s 1957 novel, Voss, whose doomed fictitious hero was based on German explorer Ludwig Leichhardt. Ho’s hero is Harold Lasseter, the entirely real but also possibly insane charlatan who claimed to have found a rich gold reef in Central Australia as a young man, and determined to relocate it with an expedition during the Great Depression. It’s an Australian El Dorado myth, and Ho employs it as a means of skewering our country’s tendency to eulogise itself.

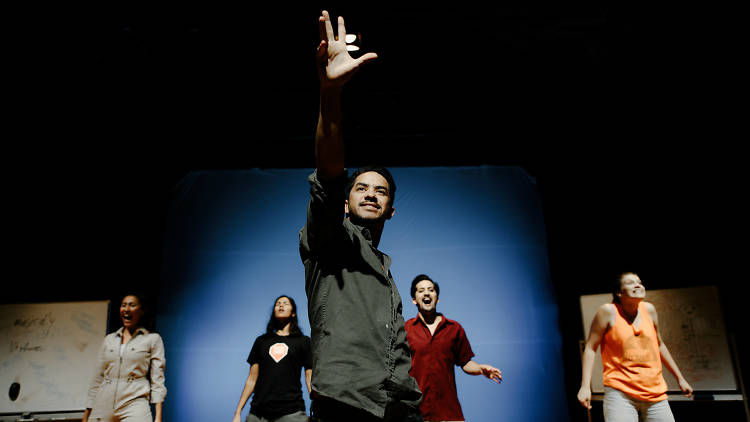

If only the audience were as familiar with the backbone of the story as Ho seems to expect. We enter the myth via a long monologue delivered from behind a black curtain by the actor who plays Lasseter (Sermsah Bin Saad), but without a scrap of context, it doesn’t make much sense. This is followed immediately by a meta-conversation between actors peppered throughout the auditorium about arts funding and cultural cachet. What comes next is neither a straight rendering of the tale nor a wholly realised satirical takedown of it, leaving the audience very much on the outer.

Being on the outer is, in some ways, part of Ho’s point. The national mythologies that prop up our sense of fairness are woefully inadequate in a multicultural society, and The Great Australian Play attempts to upend our assumptions about, and disturb the equilibrium of, our shared narratives. But then the playwright relies so heavily on insider jokes and insular references, it’s hard to pick the targets of the satire. It is often difficult to work out just who the piece is intended to entertain.

Every now and again, the play throws up an image of genuine horror and subversion – a vignette that involves an actor pitching a script to a dead kangaroo is hilarious and chilling in equal measure – but there are simply too many targets and not enough discipline for the punches to land. Long sequences, of a woman using a dildo to fuck the Earth, or a family repeating a dinner made up almost entirely of non-sequiturs, are more pretentious than portentous, and the result is merely tedious.

The direction by Saro Lusty-Cavallari is part of the problem; ludicrous longueurs cripple the pacing, but key moments are rushed and ineffectual. The performances are simultaneously over the top and underdone. It’s almost as if the work had too many ideas in the mix, too many directions it wanted to explore, and decided to walk every path. It means we end up in some fabulously weird places, but also essentially nowhere. As a metaphor of Lasseter’s folly, it’s apt, but it’s also not much fun.

Ho fashions himself as an iconoclast, and by including himself in the cast he makes the play ultimately about himself. A late discursion involving Ho and Patrick White in conversation – via Brett Whiteley’s painting of the late novelist – is telling. Ho has previously won the Patrick White playwriting award, so the whole show can be read as an example of the anxiety of influence. If the outcome is less than a heartbreaking work of staggering genius (and certainly far short of a great Australian play), then at least it’s an example of a writer seriously wrestling with the major lies at the heart of our nation. I’d rather that than a safe confection any day.