“Man does not create gods, in spite of appearances. The times, the age, impose them on him”. It’s a gendered response to the overwhelming subservience of belief and the dumb power of the zeitgeist, but it isn’t less true for that. And it’s a direct quote from Stanisław Lem’s extraordinary cult 1961 science fiction novel, Solaris. A work that has had three film adaptations – a rarely seen 1968 Soviet TV play, the seminal 1972 Tarkovsky masterpiece, and Soderbergh’s noble 2002 version with George Clooney – it now comes to us as a stage adaptation for Malthouse Theatre, by Scottish writer David Greig.

Every adaptation of this work makes major alterations to the story, which of course are a legitimate response to the times, the age in which they are produced. But not a single one has captured Lem’s intellectual daring, his scholarly penetration into the means and morality of exploration. His imagination is closer to writers like Italo Calvino and Jorge Luis Borges than science fiction greats Asimov or Clarke – his expansiveness is meticulous and his questions unanswerable. Whatever you think of the various adaptations, Solaris the novel is a flat-out masterpiece.

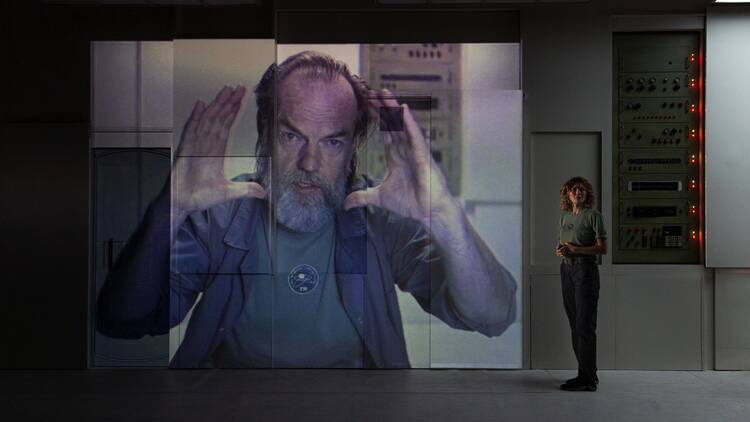

Kris Kelvin (Leeanna Walsman) arrives at the substation hovering just above the surface of Solaris, the planet covered entirely in ocean that orbits around twin suns, a red and a blue one. The astronauts living on the substation are Dr Snow (Fode Simbo) and Dr Sartorius (Jade Ogugua); the only personal connection Kelvin has is to her mentor Dr Gibarian (Hugo Weaving), who is already dead and appears via video projection. Everything seems pretty relaxed, except for the “visitors”, ghostly manifestations of the crew’s past relationships that clearly don’t belong in outer space and, rather inconveniently, refuse to die.

Some of Greig’s changes are inoffensive, if inconsequential. Switching the genders of Kelvin and the dead lover Rheya (here called Ray and played by Keegan Joyce) mightn’t achieve much but does mean we get Walsman as our protagonist. She is a fine, beautifully responsive actor and is in terrific form here (she featured in Lutton’s stage adaptation of Melancholia last year, so maybe next year she’ll play HAL). Joyce plays the substitute Ray as a kind of dangerously boisterous rag doll for much of it, and never quite hits the character’s existential horror.

But some changes are problematic. In the novel, and film adaptations, Snow and Sartorius are psychically damaged people, having endured the renting emotional turmoil of afterlife visitations for years. Here, they are perfectly sane and unperturbed. Changing the nature of the visitors, who are now merely nice simulacra of lost loved ones, means the whole layer of guilt and suppression is lost. Kelvin feels directly responsible for the suicide of Rheya in the novel, which gives the relationship a darkly seductive codependence; Greig’s version is infinitely more banal and simplistic.

The nature of Solaris itself is also fatally compromised, largely for the sake of some painfully obvious observations about humanity’s destructive tendencies. Lem is deeply concerned with human exploration, with the limits of human imagination and ingenuity, and of the great gulf between our desire and our ability to communicate with ourselves and the other. Greig has taken character names and vague, if misunderstood, thematic concepts from the novel, but he reduces almost every intellectual idea at play to schematic rubble.

Lutton’s direction is problematic too. The pacing is monotonous, if never exactly boring, and the stakes are low. There is little sense of dramatic crescendo or even moral inquiry, so moments of panic are purely surface. Simbo is a likeable presence but lacks depth, and Ogugua never convinces as a scientist who uses her methodology to paper over welling grief. Only Walsman seems truly committed, and manages to make her ethical conundrum central emotionally as well as dramatically. And Weaving, his craggy face looming and his eyes sparking intelligently, is remarkable.

The set design (Hyemi Shin) and lighting (Paul Jackson) are initially impressive; the rectangular white box, with its modular furniture and sliding panels, feels suitably oppressive, and the heavy red and blue of the suns keeps the nearby planet constantly in mind. But then, nothing changes and the effect flattens out. Given the limitless potential a project like this promises, the overall impression is bland.

Metres away from this production, Wake in Fright proves the power of intelligent adaptation, of a genuine theatrical vision that engages with the original source material and comments cleverly on its film history. Solaris shows us the opposite, a humanity scrambling under the weight of a genius it doesn’t understand. The anxiety of influence is crushing, and the effect is rather like the visitors themselves: surface toys without a soul. If this is what the god of our age imposes on us, then it’s hard to blame Kelvin for choosing to stay on Solaris.