The art of translation is not to slavishly reproduce the beats and rhythms of the original work, but to capture in some way its essence while striking out in original directions of your own. Playwright Fleur Kilpatrick pulls off the fiendish task of adapting Kurt Vonnegut’s seminal anti-war novel Slaughterhouse-Five to the stage, and the result is thoughtful and often chilling; if it’s not as sustained a scream for our lost humanity, then at least it’s a powerful damning of our ongoing lust for war.

Vonnegut’s novel concerns itself with the bombing of Dresden, something the author actually survived as a prisoner of war in the latter months of World War II. But far from a straightforward telling of this event, the work is shot through with science fiction tropes: the protagonist experiences unexpected leaps through time, and is convinced he’s been abducted by aliens from a planet called Tralfamadore. It’s a bizarre melding of autobiography, philosophy and black humour, and Kilpatrick approaches the material by jumping straight into the deep end.

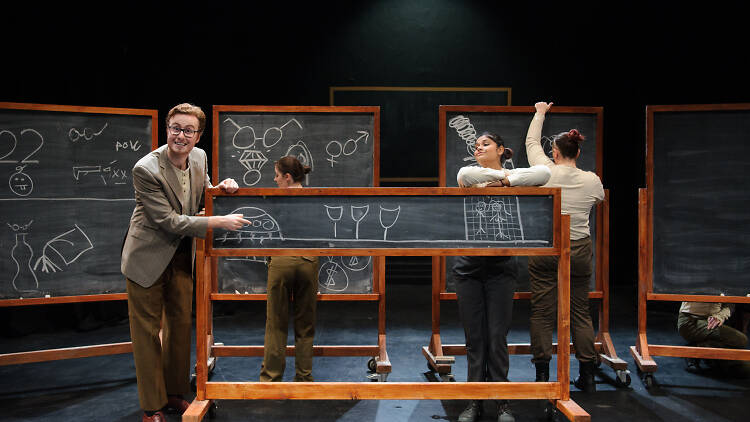

The play opens with Vonnegut (Sam Barson) himself explaining the genesis of the novel, his part in the war and the ultimate inadequacy of language in the face of such slaughter. He then transforms into Billy Pilgrim, optometrist’s son, wide-eyed innocent and hopeless soldier. The cast explain and illustrate the entire chronological life of Billy with the use of a series of movable blackboards and chalk drawings, from a plane crash that he alone survives, to the birth of his children and the death from monoxide poisoning of his wife, to his eventual assassination by sniper attack.

But Vonnegut isn’t interested in chronological time, in the simplistic notion of cause and effect, and neither is Kilpatrick. The play adopts a scattergun approach to the narrative, which loops and repeats and folds back on itself, always circling the dreadful allied destruction of Dresden like an itch it must keep scratching. This makes for an unevenness in pacing that occasionally drags, most noticeably in the second act, but that also underlines a key point of the work; mass murder has no logical line of argument, and no amount of rationality will make meaning out of it.

Kilpatrick directs Monash University Student Theatre actors with great assurance, tapping their energy and enthusiasm. The ensemble may be a little uneven, but they display heaps of versatility and commitment. Their relative youth also adds poignancy to the idea of war as something “fought by babies”. The ingenious stage design (Jason Lehane) and effortlessly evocative costumes (Dil Kaur) keep the work moving, and Justin Gardam’s sound design is chillingly atmospheric. Technically, it’s a terrific endorsement of the idea of professional and student theatre collaboration, and we should see more of it.

Slaughterhouse Five is sadly never likely to fall into irrelevance. Pilgrim’s Tralfamadorians see time and death in a way that insures them from grief and loss, but we humans have no choice; we must experience the full horror and guilt of our actions, as the slaughter of innocents falls like ash over our planet. Kilpatrick’s final image, of the cast chalking up death in lots of five on the blackboards, is simple and grave, and functions as much as a warning for what’s to come as a lament for what’s been lost.