When Heraclitus said that you can’t step into the same river twice, he may as well have been talking about the Swan as it flows into Perth, the setting for Tim Winton’s seminal novel Cloudstreet. Of course the Greek philosopher didn’t care which river it was; he was making a point about change, about the impermanence of experience. He also said that everything flows, that nothing stays still, and again he could be summing up the novel’s central theme. Twenty years have passed since Malthouse’s previous production of Justin Monjo and Nick Enright’s stage adaptation of Cloudstreet, and so much has changed, so much water – not to mention blood and guts and rage and grief – has flowed into and out of the tributaries of our cultural landscape, that it feels like an entirely different work, the answer to a question we couldn’t even articulate back in the late ’90s.

Winton’s novel is a cultural touchstone, and the original stage production, directed by Neil Armfield, is embedded in the theatrical memory. Which makes Matthew Lutton’s decision to program it – with small but significant changes to the script and a design aesthetic that seems diametrically opposed to Armfield’s – a bold and powerful one in its own right. The key shift is in the casting: not only is it racially diverse, the actor playing Fish Lamb, the golden child who drowns at the beginning of the play but who is revived with major neurological trauma, is played by neuroatypical actor Benjamin Oakes. In some ways, this is a challenging of the source material; Winton’s novel has a tendency to exoticise both its Indigenous characters and Fish’s disability, and Lutton, it could be argued, is redressing an imbalance.

But it is only partly successful. The boosted presence of Indigenous actors throughout is welcome; it isn’t only diverse for diversity’s sake, it deepens and layers the theme of disparate mobs coming together, the house as synecdoche for nation. An emphasis on the history of number 1 Cloudstreet, its brief use as a mission for “native girls, taken from their families”, and the addition of Noongar language in the script, seems sound in theory but the effect is often confused and contradictory. By amplifying the First Nations presence as “other” to the inhabitants of the house, it cuts against the racial diversity inside that house.

The casting of Oakes also doesn’t quite deliver on its promise. An autistic actor who has worked with the extraordinary Back to Back in Geelong, he is endearing and attentive, a convincingly-loved and vital member of the Lamb mob, but his performance never hits the expansiveness the role requires. The relationship between the brothers Fish and Quick Lamb is Cloudstreet’s spiritual spine, and neither actor pulls it off. Back to Back build their shows around their performers, who are also their key creatives; unfortunately that experience hasn’t prepared Oakes to carry a show like Cloudstreet.

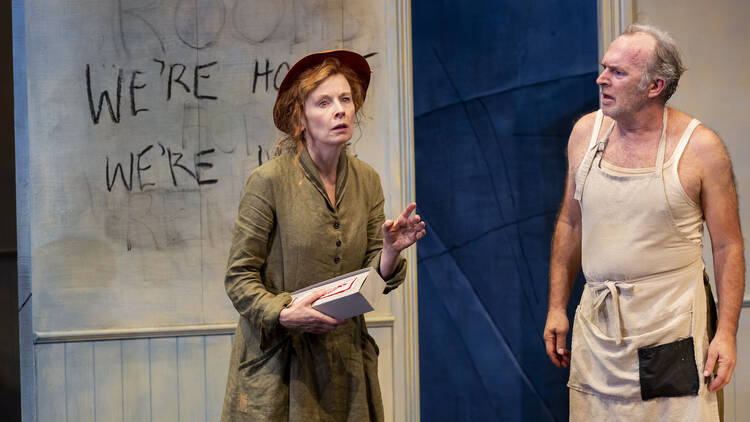

It isn’t all loss. Some actors carve career-defining performances from the work, even while others fade into the background. Alison Whyte’s Oriel is a tour-de-force from go to whoa; harried, stringent and cruelly uncompromising, she manages to turn the character’s intractability into something endlessly revealing, as if she is drawing us further and further into the rooms of Oriel’s soul. Natasha Herbert, initially rather one note as the slatternly and gauche Dolly, undergoes a transformation in the third act that is devastating and true, a dam busting over the audience in waves of grief and humanity. As the husbands, Bert LaBonté is his usual offhanded self as Sam, adorable and frustrating in equal measure, while Greg Stone as the more conflicted Lester is sublime (is it us or is this actor getting better and better?). Brenna Harding is the only one from the younger generation who traces a whole life as Rose, even if she has to deal with some major inconsistencies in her character’s motivation.

The set design (Zoë Atkinson) is the production’s greatest obstacle, one it can’t overcome. The house on Cloudstreet, which functions throughout as a central character, is here depicted by three dreary and uncompromising walls in a rusted grey–blue, the outlines of human figures suggesting the shadows of Hiroshima victims as much as Indigenous cave paintings. Interior walls slide endlessly in and out, and water is sporadically introduced both from below and above, but there is so little magic generated it often feels like money down the drain. Paul Jackson’s lighting and J David Franzke’s sound are tediously insistent and overdetermined – sudden blackouts and gunshots might augment drama but they cannot substitute for it.

Maybe, like drugs and sex, theatre’s simply never as good the second time around. Those of us who remember Cloudstreet as it was, with Armfield’s expansive, abstract set and joyous, celebratory lens, will find it hard to enjoy this thoughtful but occasionally leaden revival. Sure, there are things that needed to change, but this recalibration doesn’t always know why, or what they should change into. The inclusiveness is more inclusive, but the broad, fat spiritual rain of revelation fails to fall this time around, and I for one miss it.