In the Hindu tradition (and also in Buddhism), samsara can roughly be translated as the wheel of life, the never-ending cycle of birth, existence and death that defines the human experience, and which can only be transcended by enlightenment, or nirvana. It is almost an inevitable subject of dance: the flow of movement, its ephemeral essence, speaks directly to the cyclical nature of our world. We begin, we move, we stop and we begin again.

UK/Indian dancer Aakash Odedra has teamed up with Chinese dancer Hu Shenyuan to explore the notion of samsara as it relates to both Chinese and Indian thought. In many ways they each represent their cultural heritage on stage, almost standing in for their nations – although it is inadvisable to take the metaphor too far. China and India share some cultural similarities, but as nations on the world stage there is no helpful comparison to be made.

Nevertheless, Odedra and Shenyuan do draw on the dance traditions of their respective countries to fascinating and often stunning effect. Odedra is trained in kathak and bharatanatyam dance, and Shenyuan in Chinese folk – one of the most remarkable aspects of the performance is how fully integrated, how seamlessly contemporary the ancient dance is made to feel. It pulses with life, often breathtakingly beautiful as a breathing art form – not as mere cultural artefact.

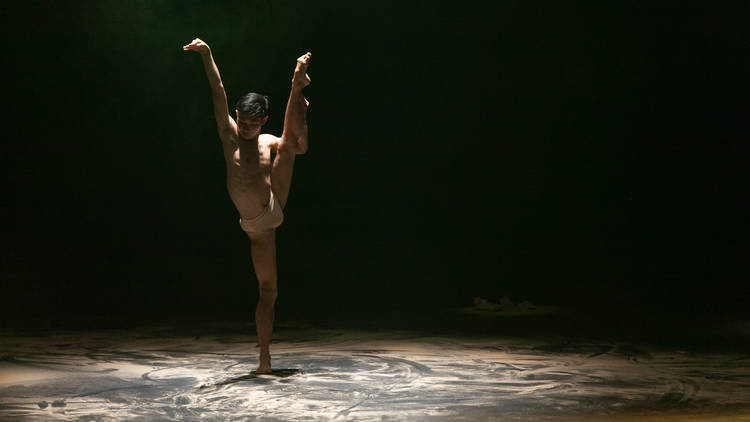

The opening is more than arresting, it’s mesmerising. A grand gong is struck, and a light comes up on a bronze statue, sand raining down on its head. Shenyuan is soon visible, bathed in golden light that still allows for plenty of shadow. In that chiaroscuro, the dancer’s lithe figure moves swift and birdlike one second, gloriously flowing and elongated the next. The contortions, the lines and the startling tableaux he creates are simply spellbinding.

Later in the piece, Odedra has his own moment to shine individually – with a routine involving spins that tilt towards the ecstatic, evoking the escalations of religious fervour – and again it is spellbinding. One sequence, so elegant in its simplicity, involves the two dancers pouring sand into each other’s cupped hands, a symbol of shared cultural associations perhaps. Or just shared humanity.

There is so much exquisite dance and so many gorgeous ideas that it’s unfortunate the piece doesn’t make an entirely satisfying whole. The opening has a sequence where the two dancers simply cross the stage in identical hooded garments to intermittent pulses of light, and it is wonderfully austere and mysterious. But when this resolves into a sequence involving squares of light – the dancers moving in and out of them, reaching for each other – it is painfully literal.

Later – when the dancers explore the idea of connection through rhythms tapped out on their bodies, or they form an image of Ganesh, with multiple limbs moving – the performance threatens to collapse into cliché. Even the image of continuous streams of sand falling is a theatrical idea that has had its day, lovely though it looks. There is a sense that the two performers ran with every idea they came up with in the rehearsal room, instead of pushing through to something deeper and more dangerous.

Samsara is a work that aims to build connective tissue between different cultural traditions and on this level it is a success. This isn’t a crucible, where separate forms melt into each other, losing their specificity. But despite some technical triumphs – Yaron Abulafia’s magnificent lighting design and Nicki Wells' extraordinary score elevate the emotional effect considerably – and a heap of gloriously precise and expressive dance, it doesn’t achieve greatness. It needs an outside eye, a singular vision, for that. Still, samsara is an ongoing process of imperfect repetition. The work is just beginning. Again.

Review

Samsara review

Time Out says

Details

Discover Time Out original video