You’ve never walked into a space as cacophonous as the Substation in Newport, showing Steven Rhall’s Defunctionalised Autonomous Objects. It’s noisy, overwhelming and there’s a twist at every turn.

The exhibition is one of the Taungurung artist’s first major shows, after having shown both in group and solo exhibitions, albeit not quite to the scale of this show. You may have seen his work, The Biggest Aboriginal Artwork In Melbourne Metro (2014-2017) either while it was in-situ on Paisley St, Footscray, or when it was lifted from its street context in the Sovereignty exhibition at ACCA. Or you may have seen it, you know, on the internet. But his work goes far beyond that. It’s considered, it’s often tongue-in-cheek, and it’s often iterative. And it’s art like you’ve never seen it before – inciting curiosity with a questioning that’s often both smart and smart-arse.

The artist looks at different themes and issues in the world around us, not just focusing on one topic, but spreading his interests to the way that our cities are designed, the proclamation of power in both public and private spaces, the influence of underground culture and resistances within broader society, and the way that images and text are read in these different situations.

He also questions notions of what art can be, and the ways in which art made by Indigenous peoples has been profited from. Art made by Aboriginal peoples in Australia has boomed since the late 1970s and early '80s, and historically, the perceptions of what Aboriginal art can be was determined without Indigenous people in the room. Rhall, and many others, are taking back control. In Rhall’s case, it’s by averting definition and creating an ambiguity that unsettles. You don’t even know where the finger’s being pointed – or who it’s being pointed at, let alone if there’s a finger there in the first place.

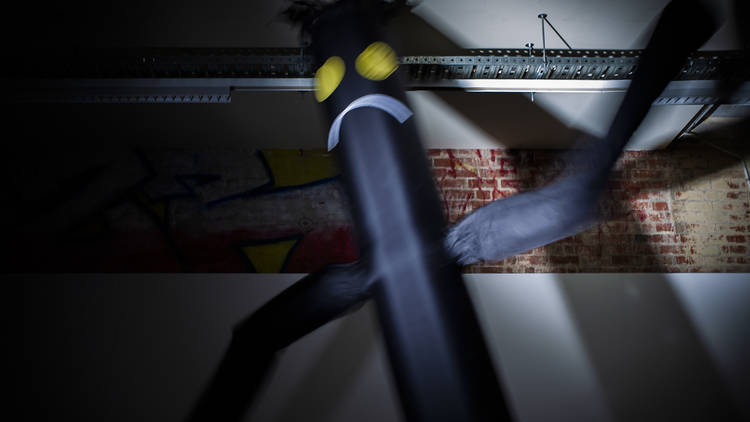

Walking into Defunctionalised Autonomous Objects, the first thing that overtakes your senses is the rush of noise coming from one corner of the building – it’s like a Dyson that’s been manipulated by Elon Musk, so powerful is the sound. You’re immediately drawn to it, only to find yourself alone in a room with an air dancer – the kind you see outside car dealerships – though this one’s black and unhappy.

The description of the exhibition states that “The first art museums were spaces of conquest – when they weren’t showcasing items pillaged from non-European cultures, it was the very bodies of those people put on display.” The air dancer appears to be an example of an unease in the way that both museums and art institutions have taken ownership not only over Indigenous objects, but bodies (both literally, and figuratively) as well.

You’ll smell the acrid scent of a fire that’s been extinguished, and that smell leads you to a hole in the wall that exposes the underneath of the room – you look through the hole, and you can’t quite tell what’s down there, but there’s a strobe and what looks like a waterslide plunging underground.

Throughout the exhibition, you’ll notice video screens. They’re broadcasting the exhibition space and you’re not sure whether they’re watching you watch them in another part of the building, or whether they’re watching you watch the art. There’s also rectangular holes cut through parts of the walls so that you can see from one end of the building to another, where an artwork hangs. Here, the artist makes you question not only what you’re observing, but whether you’re being observed too, and what the power relations are between these observations. Electrical cords and lines cut through and separate the spaces – it could be a reference to the compartmentalisation of Indigenous bodies and cultures by Western museums.

The space is labyrinthine, and you’ll find yourself in parts you have no idea existed. Rhall has utilised one of the basement levels to lay out an installation of body bags (the kind you use in quarantine), carving objects, a collage, and a table displaying tattoos that make reference to all manner of things – from colonisation (a ship atop a British flag), to art making, to graffiti. It’s almost like he’s drawing a line between graffiti on walls, and institutions on the body. That thematic comes more heavily to the fore when you see a photograph of his naked bottom, with the words “Arts tattoos divide, paint drawing implement/s, drawings, floor drawing, variable (2018)” on one cheek, and “Aboriginal electronic input, a public, timbre rail, sequential display of dimensions” on the other. He actually had it tattooed.

There’s much more to the exhibition – it’s a real must see and a sensitive and thought-provoking questioning of the power in representation, the art institution, and Australian society.