Who is conceptual art for, and who gets to make it? With a commitment to exploring the complexity of identity, championing the “other” and “blackening of the conceptual art canon”, artist Newell Harry might just alter your perception.

Esperanto, the artist's largest solo project to date, is now open at the Murray Art Museum Albury (MAMA), and it's the perfect calling card to prompt you to make the journey to visit the regional centre of Albury Wodonga and its striking art museum. You may know MAMA as home to the National Photography Prize. This new exhibition marks the first time the gallery has presented a major solo exhibition of works by a contemporary Australian artist.

The desire for universality, something that can traverse culture and dialect, is there in all of Newell's work.

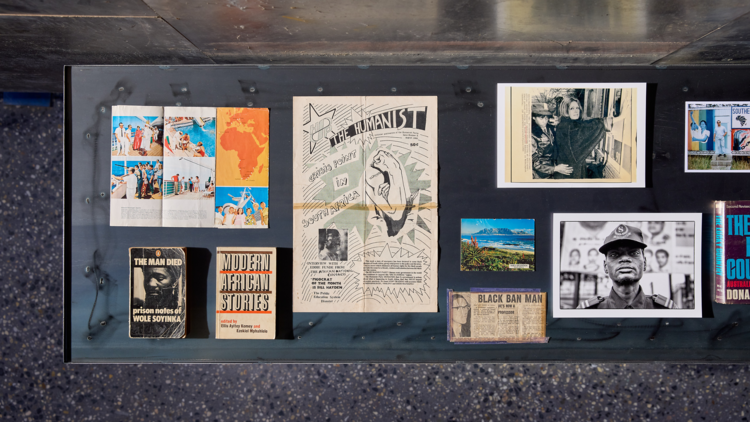

Harry’s multidisciplinary practice bundles together found objects and museum-style curation with original pieces, exploring family stories of migration and care, and ideas of trade and gift giving with a subtle anti-capitalist thread running throughout. An Australian-born artist of South African and Mauritian descent, Harry draws from an intimate web of connections across Oceania and the wider Indo-Pacific. Esperanto recognises pivotal moments in Australian, South African and Indo-Pacific histories of the ’60s and ’70s, such as the end of the White Australia Policy, the 1967 referendum, anti-apartheid rugby protests, environmental and anti-nuclear testing movements.

Whilst perusing Esperanto, you’ll come across towering prints of wordplay; artefacts of Indo-Pacific pop culture and art history; entrancing reels of documentary film; family photos; and the strange, almost menacing nostalgia of a slideshow of a stranger’s holiday snaps (literally, the slides were discovered by Harry on the side of a road in Annandale) contrasted with written segments of the bizarre dictation tests that were part of the White Australia policy. Throughout all of it, a dry sense of humour pervades.

The exhibition borrows its name from an artificial language devised in 1887 by the Polish ophthalmologist (an eye doctor) L. L. Zamenhof, which was intended to be a universal second language. Michael Moran, acting director of MAMA and exhibition curator, worked closely with Harry on the exhibition. As he explains: “It's a beautiful idea [esperanto], and it's a utopian idea. I think we all appreciate that approach. But of course, it's a failed idea. It didn't really take off, and again, it was a very Eurocentric idea.”

Moran continues: “It's a metaphor for how this project can function, the hope is something beautiful. That failed progressivism is something to be reflected upon. The desire for universality, something that can traverse culture and dialect, is there in all of Newell's work. It's something to be negotiated with constantly.”

Photograph: MAMA/Jeremy Weihrauch

Photograph: MAMA/Jeremy Weihrauch

Despite its regional location, Esperanto has numerous links to Sydney (where the artist was born and where he lives and works now, in addition to Port Vila, Vanuatu). This is most evident in ‘Untitled (The Point)’, a new large-scale photographic commission unveiled as part of the exhibition. The series evokes the forgotten histories embedded in Sydney’s Callan Park, on the foreshore of Iron Cove on the Parramatta River. A site of substantial trauma and dispossession, and once a lavish private residence, Callan Park was used as a psychiatric hospital for many years.

Harry’s photographs tell the story of a pair of clairvoyant Maori twin brothers who were detained at Callan Park. The brothers’ rock carvings from around 1880, found in an area known as The Point, correctly foretold the life of Tahupōtiki Wiremu Rātana, his founding of the Rātana Church (a Māori Christian denomination), and numerous events that occurred across the Pacific Ocean. The work obliquely allows the dominant and hidden narratives of the site to co-exist, enforcing an idea that our histories and knowledge systems are always in contest and truth is far from immutable.

Some of the works on display are on loan from the Art Gallery of New South Wales, including the 1880 oil painting ‘Race to the market, Tahiti’ by the Russian artist Nicholas Chevalier. As a child, this painting was Harry’s most favourite one to see at the Gallery, apparently because the dog in it so closely resembled his own. In a glass cabinet adjacent to the painting, you’ll notice a print of the work. This was acquired by the artist at a rummage sale at a house he was randomly passing one day. Not only did he find this reproduction of his favourite childhood painting quite by accident, but he then discovered that it belonged to an acquaintance of his auntie, who had her own connection to travels through the Pacific which mirrored his own. This is just one example of the complex serendipity that runs through this exhibition.

Not only knowledge, but how we accumulate, how we store and how we share knowledge is challenged by this work...

While Esperanto contains more than one unlikely tie to Sydney, there is also a fortuitous significance to it being hosted on the border of New South Wales and Victoria in Albury. The city is a great centre of migration, with one in six Australians having a connection to the Bonegilla Migrant Centre. And that’s not all – as Moran explains: “We thought, you know, a show about failed progressivism and the ’70s really would have a good home in Albury, right? This was part of [Gough] Whitlam’s grand decentering project. Like, they moved to the ATO here. Still, when you get audited, someone in Albury is doing it.”

Esperanto presents the breadth of Newell Harry’s practice, woven together in a complex network of ideas and narratives. It’s an exhibition that you really want to spend time with, leafing through its many layers. Like all great art, it can be enjoyed without the need to elaborate, but you can draw so much more from it by booking into a guided tour, or simply by bending the ear of one of the gallery attendants.

“In all of this, there's that idea of disassembling grand narratives and the master narratives,” says Moran. “Not only knowledge, but how we accumulate, how we store and how we share knowledge is challenged by this work – and not in a way where it's a dichotomy, but it's open, layered, complex, and irresolvable.”

Newell Harry: Esperanto is showing at MAMA, Albury, until November 26, 2023. The exhibition is free to visit. From Melbourne, Albury is a 3.5 hour drive, or you can catch a train (3 hours 20 mins) for as little as $8. Find out more about the exhibition at mamaalbury.com.au.