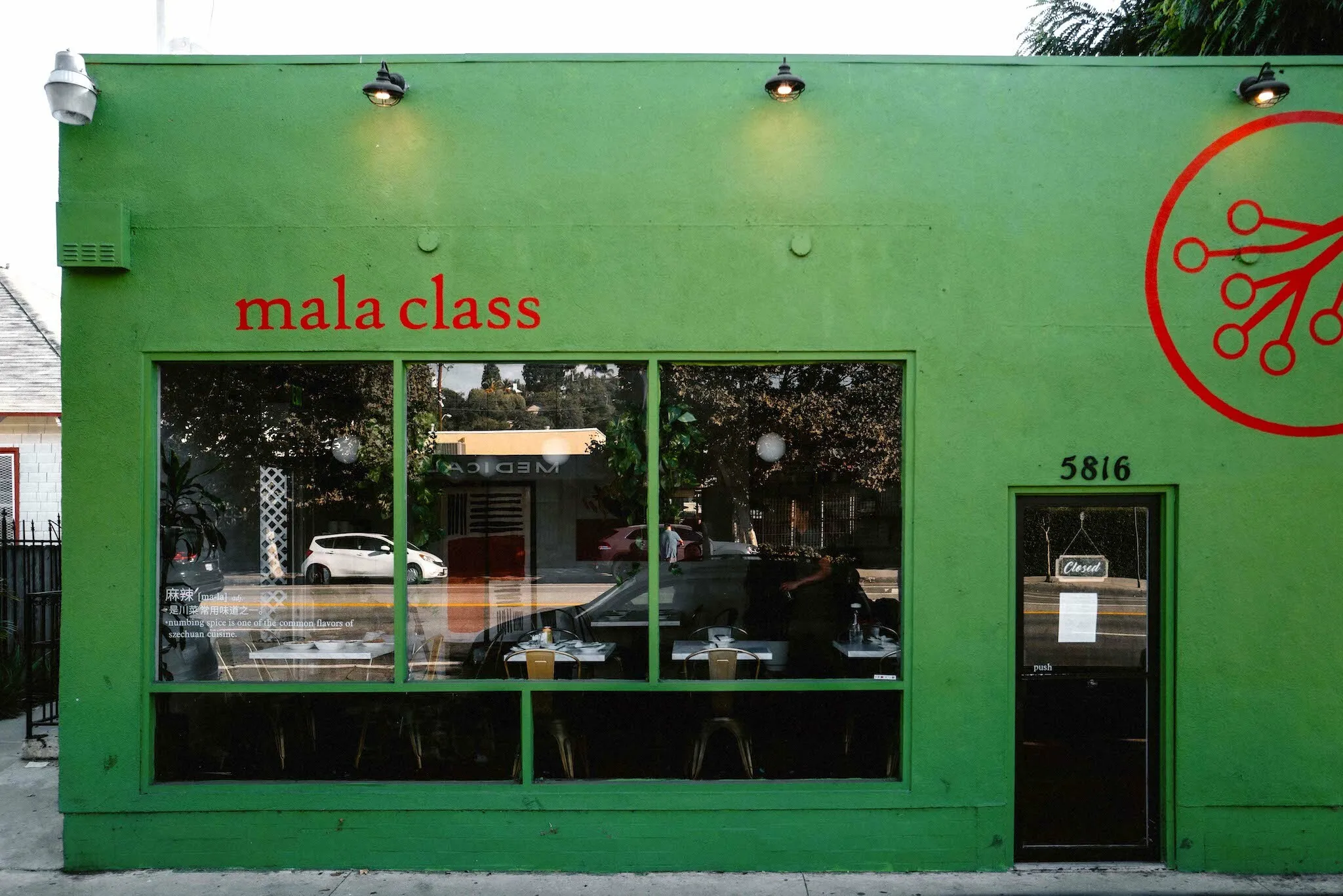

For several months, Highland Park area residents speculated about what would take over 5816 York Boulevard. A yoga practice, perhaps? Once signage for “Mala Class” appeared, some wondered if the former Salvadoran restaurant might transform into an arts and crafts studio. (In addition to the feminine version of “bad” in Spanish, mala also translates to “garland” in Hindi and Urdu. It can also refer to the prayer beads used in Hinduism and other South Asian religions.)

It wasn’t until the end of June that co-owners Kevin Liang and Michael Yang opened their brightly colored fast-casual Chinese restaurant, clarifying the name’s intended meaning. Málà, as the term is accented in standard pinyin, refers to the unique numbing, spicy flavor profile most commonly associated with Sichuan, the southwestern Chinese province known for its bold, pungent cuisine full of garlic, chilies and peppercorns.

With a modern, nuanced interpretation of the region’s cooking, Mala Class—which I recently awarded five stars—is easily the most interesting Sichuan restaurant in Los Angeles to open in the last decade. Drawing inspiration from the East Coast’s Han Dynasty (where the two first met, and one of NYC’s best Chinese restaurants) and their families’ combined experiences in the restaurant industry, Liang and Yang have created a winning formula: a reasonably priced, approachable Sichuan menu still capable of delighting diners familiar with the cuisine’s tongue-tingling thrills.

Yang, a Sichuan native who most recently cooked at Bistro Na’s in Temple City, displays a level of technical precision that makes a simple meal at Mala Class shine even in L.A.’s competitive Chinese dining scene. The flavorful, satisfying dan dan noodles offer just the right amount of bounce—a sought-after textural quality known as QQ across the Sinosphere—and Mala Class’s subtly electrifying mapo tofu is the best version of the dish I’ve had in the city. Much of the menu is plant-based or can be modified to become vegan or vegetarian. Craveable appetizers like cumin-dusted mushroom fries, mixed greens with Sichuan-style dressing and mala chicken wings are designed to inspire return visits, and boy, do they do.

“People understand Sichuan food, but they don’t really know Sichuan food,” says Liang, who runs front-of-house. He spent several years in management and operations at Han Dynasty. The tri-state Sichuan chain was originally founded in Philadelphia, where Liang spent his formative years and later majored in kinesiology at Temple University. His immigrant parents ran a Chinese takeout restaurant growing up, then moved to L.A. while he was in college to take over Inglewood’s Louisiana Fried Chicken. (They still run it today.)

In late 2019, Yang—the culinary lead of the duo—approached Liang with a proposal for an L.A.-based Chinese restaurant concept; like Liang, his parents had settled in greater Los Angeles, opening and selling a pair of Sichuan restaurants in the San Gabriel Valley. “We came out that September thinking that, ‘Oh, we can open a restaurant right away,’” Liang recounts.

For two and a half years, the pandemic put those plans on hold. Initially, both co-owners helped keep their parents’ businesses afloat, then found other jobs in the restaurant industry; Liang at Pasadena’s Bone Kettle, Yang at Bistro Na’s. They scouted for the right location, painstakingly developed the opening menu and, of course, ate at many of L.A.’s Chinese restaurants and hot pot joints in the name of research and development. Their self-funded Highland Park restaurant, which they signed the lease for in May 2022, has been five years in the making.

If you’re remotely familiar with L.A.’s Chinese dining scene, you probably know that Sichuan cuisine first took the city by storm over a decade ago with the openings of Chengdu Taste (2013) and Sichuan Impression (2014). Alhambra’s Chengdu Taste still occupies a spot on our Best Restaurant list, and for good reason. Since then, plenty of other copycats have opened, while out-of-town chains like Sichuan’s Hao Di Lao and NYC’s Szechuan Mountain House have cropped up in greater Los Angeles. Thanks to the clever marketing tactics of “cool” brands like Fly by Jing and Momofuku, Sichuan-style chili crisp and other similar products have become a sought-after gourmet pantry item nationwide.

The city’s collective obsession with málà extends to the fast-casual realm, a price point and style of service I’m drawn to for personal as well as editorial reasons. The most memorable local example up until now has been Mian, a noodle concept from the team behind Chengdu Taste with locations in West Adams, San Gabriel, Rowland Heights and Artesia. In late 2023, Fly by Jing founder Jing Gao and the influencer Stephanie Liu Hjelmeseth also opened Suá Superette, a Pret a Manger-inspired concept in Larchmont. In the last 10 or so years, I’ve dined at all of these places. Since my first visit to Chengdu Taste, I’ve yet to find a Sichuan restaurant that has captivated my tastebuds and interest more than Mala Class.

Despite the menu’s small size, the contemporary Sichuan fare leaves a memorable first impression. Finer details like noodle texture and the crispiness of dry pepper fried tofu have not gone unnoticed, by me or the growing crop of returning customers Liang and Yang have amassed. Mellow leeks and a subtle but clearly evident numbing quality in the mapo tofu elevate the ubiquitous dish from merely reliable to truly, deeply great. Tossed tableside, the dan dan noodles come in a spicy, garlicky, slightly creamy sesame sauce that tastes nothing like the sad peanut butter-like versions I’ve been unfortunate enough to encounter elsewhere.

While explaining Mala Class’s name, Liang says, in essence, that the restaurant serves as an introductory lesson in Sichuan cuisine. Yang often tells him stories about his childhood growing up in Sichuan and the dishes he grew up eating. The region’s heavy use of chilies is grounded in traditional Chinese medicine, Liang says. “It’s these little things that make Sichuan food special that people don’t know about.”

“I try to share these stories with [customers] and let ’em understand the culture more,” he adds. “It’s almost like taking everybody to a class, because I don’t know how many times people will come in and be like, ‘Oh, I want the mala chili oil.’ Well the chili oil isn’t má [numbing], it’s just spicy and very aromatic. People get the wrong impression of Sichuan peppercorn because it’s always paired together with spice, but they are separate things.”

Like Liang and Yang’s previous employer, Han Dynasty, Mala Class positions itself as an approachable gateway into Sichuan cuisine in an area with minimal competition. (While Highland Park does have Joy and Mason’s Dumplings, both offer different styles of Chinese cuisine.) What the pair hope for in the long run, however, is to be able to maintain the menu’s current level of quality and consistency, even when Yang is no longer the day-to-day chef working in the back. Their restaurant’s tree branch-like logo signifies the duo’s North Star: eventually, they want to open other locations.

The food at Mala Class might possess an artisanal level of culinary excellence, but Liang and Yang are ultimately businessmen. The co-owners quietly take pride in their three-month-old restaurant’s bouncy noodles and clever appetizers. That being said, their long-term goal with the modern Sichuan concept is to expand to multiple locations and, hopefully, amass enough wealth to help their immigrant parents retire.

“Ultimately the goal is to make money and be successful and do all that. But it’s also at the end of the day, to retire our families,” says Liang. Both his and Yang’s parents have spent almost the entirety of their careers in the restaurant industry. They’ve seen how much they’ve worked, and how hard they’ve worked. “We’ve got to figure out something to get them out of it. Having one restaurant won’t do that.”

His dad never wanted him to go into the industry, Liang adds, though he’s warmed to the idea of his son being his own boss. His parents haven’t been able to dine at the Mala Class themselves—both Louisiana Fried Chicken and Mala Class close on the same days of the week—but they’re proud of his newest restaurant endeavor, he says, especially now that the restaurant is getting busier.

“They’ll call me every night and ask, ’How much money did you do?’ It’s not, ‘Hey, how are you doing?’ It’s ‘How did you make tonight’?

Mala Class earned five stars from us. For more details on food, drink and service, read our full review.