[title]

The most astounding view from the iconic Griffith Observatory isn’t up and into the stars, but down and out onto the twinkly orange lights of the Los Angeles streetscape below. That ever-present glow is as mesmerizing as it is nearly inescapable, which complicates stargazing there and throughout much of the county.

But about 60 minutes and half as many miles away, you can drive through the San Gabriel Mountains and atop the hazy inversion layer to find a mile-high observatory that’s shaped our fundamental understanding of our place within the universe—and that features the two largest telescopes in the world dedicated for public use.

“Mount Wilson Observatory is like no other,” says Michael Rudy, a telescope operator and the coordinator for the observatory’s public ticket nights. “You will never look at the sky like you will through these telescopes.”

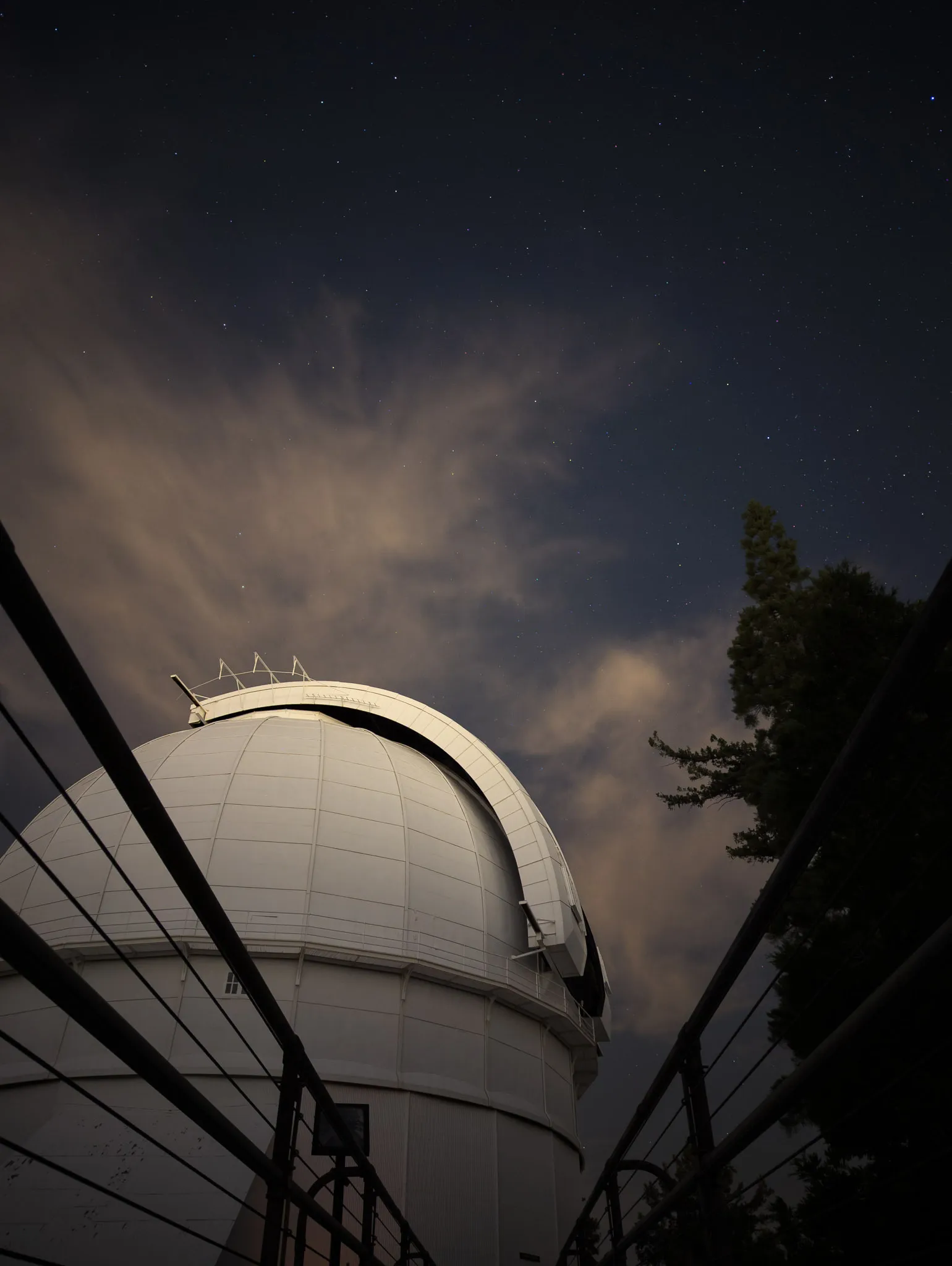

And look you can: Perched more than 5,700 feet above Pasadena, the nearly 120-year-old observatory hosts stargazing sessions inside a pair of massive domes throughout the spring and summer. Group bookings are available nearly every evening, while the coveted public ticket nights are held on select dates for individual reservations (lectures, concerts and art exhibitions round out the mountaintop programming).

Mount Wilson Observatory actually sports many telescopes, including solar towers and an array of a half-dozen relatively smaller ones that are all actively pursuing science. But its two biggest domes are reserved almost entirely for use by the public—though they do also have remarkable historical significance.

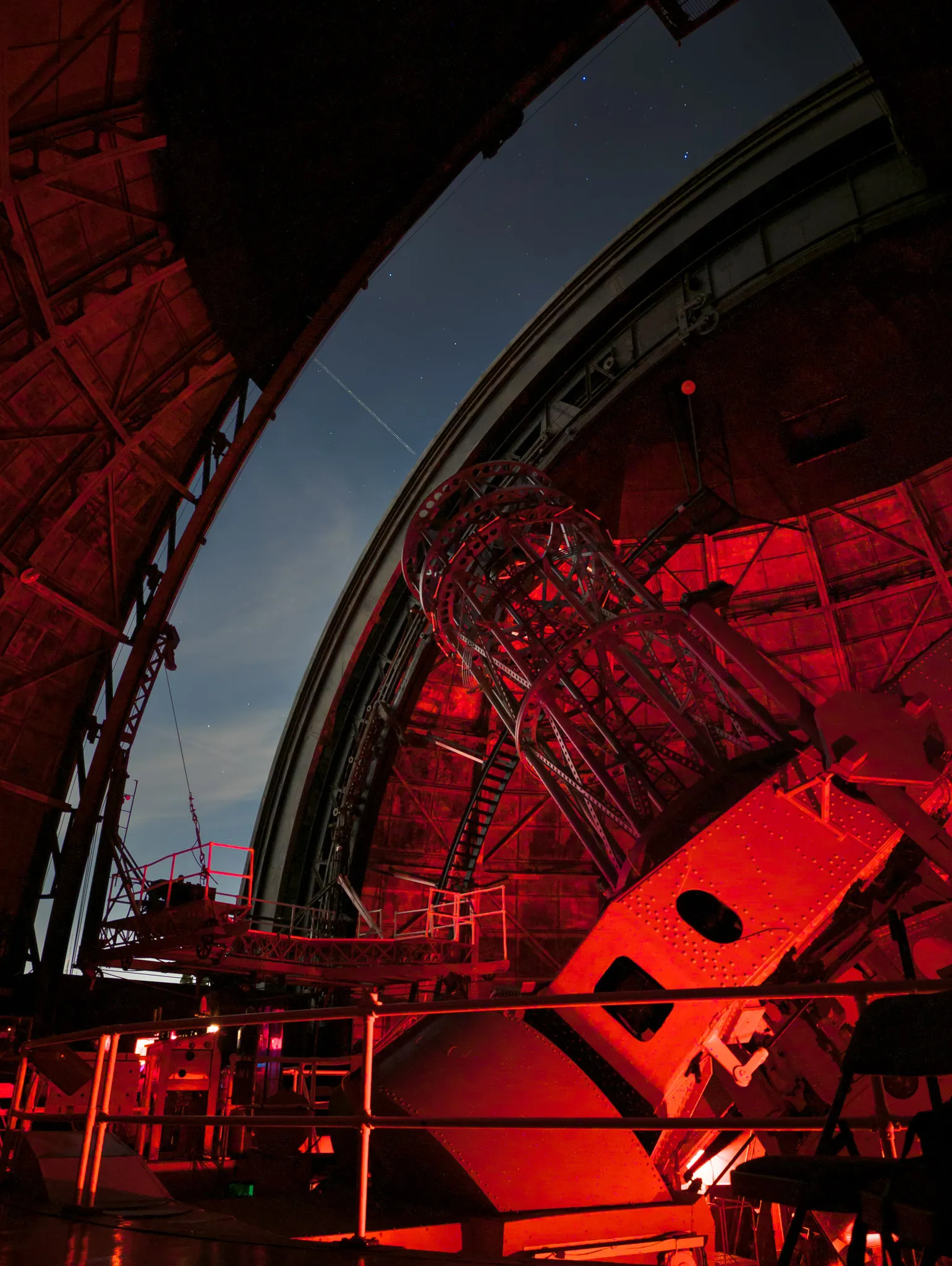

The 60-inch telescope was the largest in the world when it was completed in 1908. Its five-foot-wide mirror pioneered a number of observation methods and acted as a blueprint for just about every telescope that followed, including its neighbor less than a decade later. The 100-inch Hooker telescope absolutely dwarfs its precursor, and this too took the crown of largest in the world when it opened in 1917 (a title it held for three decades). It’s also where Edwin Hubble (as in, yes, the guy the space telescope is named after) proved that there’s more to the universe outside of our own Milky Way galaxy and that the universe is in fact expanding.

So what’s it like to actually look through them? To find out, I recently took two visits to Mount Wilson only weeks apart but with wildly different weather: a tour on a cold May Gray evening that had everyone cracking hand warmers and a stargazing session on an usually sweltering summer night.

My first visit was primarily for a guided look at an exhibition of artist Sarah Rosalena’s celestial-inspired beadwork. Though it was supposed to also include a stargazing session on the 100-inch telescope, the clouds lapping at the edges of the mountaintop meant that it was too humid to uncover the mirror, as it would immediately fog up. (Don’t worry: If you have a standard stargazing session booked, you’ll know by mid-afternoon if it needs to be called off due to weather and offered another night as a make-good.) Had it not been for the humidity, that low cloud cover actually would’ve made for excellent viewing conditions as it blocked out much of the light pollution below. Regardless, I still found it pretty otherworldly to simply step inside of the dome and soak up its astronomical history (and to soak up some actual sunlight during a relentlessly cloudy stretch of weather in L.A.).

For my second visit, I came during a so-called hyper night, where you spend two hours observing through each of the two main telescopes. It was also hyper hot, with atypical temperatures pushing 90 even as the sun was going down. This time, though, I was actually able to look through both telescopes.

It’s helpful to head into a stargazing night with some managed expectations. When we conjure up the cosmos in our imaginations, we tend to think of these vivid, heavily post-processed images that we’ve been spoiled by from the Hubble and James Webb space telescopes. But those are space telescopes, circling hundreds to hundreds of thousands of miles above the earth and free of its shimmery atmosphere.

Back here on the ground, the stars still appear pretty small and sometimes fuzzy, even through powerful telescopes like the ones atop Mount Wilson. But in spots where your naked eye might just see a twinkle or two, the telescopes reveal details hiding in the seeming darkness of space: an orange-and-blue pairing of binary stars; dense pinpoints of light crowded into globular clusters; and the colorful, neon-tinged gas of a planetary nebula. Rudy says he’s also spotted satellites, shooting stars, comets and supernovas. You can see close-ups of the planets, too, but there’s a chance they may be below the horizon during your visit; Rudy suggests using SkySafari to research what the night sky will look like on a specific date (the free Stellarium also works).

During my stargazing session, thin wisps of passing clouds bounced back some of L.A.’s light pollution. That created conditions that Rudy ranked as somewhat middle-of-the-road. Without those clouds, the stars’ contrast against the night sky would’ve been even more dramatic. Even so, after fiddling with the focus knob a bit, most of the targeted objects that evening were still clear enough to leave me in awe of the night sky.

On an average summer night, clouds aren’t much of a concern thanks to the observatory’s position above the inversion layer. “The mountain itself is the very best spot in the continental United States for seeing, meaning how steady the sky is above us,” Rudy says. “From the Pacific Ocean to this point, it’s the first peak. So the airflow is very smooth, very laminar across the observatory.”

The individual ticket nights are limited to pretty small groups; there may be a short line to step up to the eyepiece and observe, but it’s a very casual environment, with roughly 15 minutes or so spent fixed on each object. During the downtime, you’ll hear all about what you’re actually looking at, as well some history of the observatory itself: all about Albert Einstein’s visits to further his theories of relativity and how it was the site of the first major discoveries using Henrietta Swan Leavitt’s light-based breakthroughs to measure the vast distances of stars and galaxies.

I also had the privilege of following Rudy around into some of the sections of the observatory that are typically off limits to the public. As the earth rotates, so too does the night sky, and the telescope needs to compensate for that when targeting an object. Hidden underneath the floor, a colossal wheel controls the east-west movement of the telescope. With the press of a button, that wheel will then very, very slowly keep the telescope moving in lockstep with the sky. As for even aligning it with a star or planet to begin with, Rudy operates solely off a set of known coordinates—otherwise, from the upper level controls, he can’t actually see through the telescope himself to pinpoint the target.

Of course, the sliding doors on top of the observatory’s dome need to move, too, to maintain an open view of the sky. The telescope itself can tilt on two axes but otherwise stays firmly planted in place while the dome’s exterior and upper level rotates 360 degrees. From the lower level where the eyepiece is positioned and the bulk of your observation time is spent, you won’t really notice anything out of the ordinary while this happens. But during a pre-stargazing tour, the staff will treat you to this mind bending illusion from the upper level: The telescope absolutely looks like it’s moving, though the floor around it (the very spot that you’re standing on) is in fact what’s moving. Swing open the door to the dome’s exterior walkway, though, and suddenly you’ll see the foreground trees and mountainscape start to drift by.

The public ticket nights are the most straightforward way for individuals looking for some extended stargazing: Along with a small group of strangers, you can spend six hours touring and observing on the 60-inch ($105) or 100-inch ($225), while the occasional hyper night ($195) splits the time between the two. They’s both very intimate (limited to just 16 to 20 people) and exceptionally popular, so expect them to sell out quickly.

You can also book either of the domes for a private group starting around a thousand dollars—a considerable splurge, but a surprisingly sensible option if you can wrangle together about 20 other night sky obsessives. If you simply want to peer through the eyepiece, your best and most economical bet is one of the Talks & Telescopes events; these monthly Saturday night astronomy lectures are followed up with a few hours of stargazing on portable telescopes on the grounds as well as the 60 and 100-inch telescopes for only $40.

If you’re considering a session on just one telescope and trying to decide between the two, the 100-inch feels like the more momentous experience. Each does have its own viewing advantages, though. The 60-inch telescope has a wider field of view, which can actually look more appealing if you’re gazing at the moon or large planets. But the 100-inch brings more resolution and an ability to see inside objects instead of just wisps of cloud or nebula. Rudy compares it to looking at a far-away performer on a stage through binoculars: The 60-inch is like using a standard pair to see them singing and dancing, while the 100-inch equivalent would let you see if they’re lip syncing.

There are a few other practical considerations to take into account before booking, too. The 100-inch telescope requires nearly 50 stairs to reach, plus a few extra ones here and there on a step stool during the observing session. If that sounds like a challenge, remember that you’ll need to do so in much thinner air.

It’s also worth mentioning the drive up to—and more so back down from—the observatory. Realistically, an Angeleno’s average day of freeway and surface street driving is probably far more dangerous than these mountain roads. But Angeles Crest Highway alternates between winding climbs and surprisingly speedy straightaways. That feels like a bunny slope compared to the final few miles along Red Box Road’s relative black diamond. Extremely sharp curves hug right up against the mountain on the way up, with barely-there curbs and guard rails on the other side of the road. There’s at least daylight on your way up, though there’s a chance you could be navigating in dense fog.

Now take all of that and add near-pitch-black darkness on your way down, which makes tight turns seem to come out of nowhere. Moreover, you’ll likely be leaving at such a late hour that the only people on the road are exactly who you’d expect: cars with horsepower as inflated as their drivers’ egos. You’ll probably be tailgated at some point and it’ll indeed be nerve-racking—but just take your time and drive safe, and consider it a practice run for your inevitable follow-up visit.