Mix, press, roll, sprinkle, repeat, cut, rest: The average life cycle of tsukemen and ramen noodles at Chinatown’s new Okiboru takes days to complete, but the effort doesn’t go unnoticed. This streamlined restaurant on the ground floor of a luxury apartment building is one of the few ramen shops in L.A. making their own noodles.

Planting a flag near the neighborhood’s iconic twin dragon gateway, Okiboru launched earlier this month as one of the city’s few tsukemen-yas—a ramen spot focused not on the steaming bowls of tonkatsu, shio and shoyu where the noodles wait to be plucked out of the broth, but a restaurant that specializes in tsukemen, a style of ramen that serves the noodles and accoutrements separately, often to be spritzed with a wedge of lime before taking a dunk into a bowl of rich, highly concentrated broth.

“Tsukemen is starting to get popular, and I think L.A. is the perfect market for it because people are adventurous eaters out here,” says chef-owner Hyun “Sean” Park, who held positions at WP24 by Wolfgang Puck and numerous L.A. sushi shops before launching his own curry restaurant in North Carolina. Now he’s back, and with more than two years of noodle study, he’s hoping Okiboru can not only compete with L.A.’s current tsukemen Goliath Tsujita, but familiarize more Angelenos with the style of dining. But you can’t build a competitive bowl of tsukemen without the right noodle.

Photograph: Stephanie Breijo

Each day, Park and his team make separate noodles for the tsukemen ramen offerings: tsukemen cut at 2mm thick and in more of a rectangular form—better for holding the broth with each dunk—and the more familiar ramen cut at a thinner 1mm, but aged for longer. Both styles utilize the same dough, a blend of Nippon flour, one of the world’s oldest Japanese flour mills; filtered water, altering L.A. tap water’s hard pH; egg-white powder, for flavor and chew; and kansui, an alkaline solution that helps the noodles maintain their springiness.

The dough mixes by machine for 10 minutes, but the kitchen always keeps an eye on the consistency. From there, the team repositions the dough into a set of rollers, which slowly cycles the mixture back and forth in an effort to flatten into sheets and sprinkles them with thin streaks of cornstarch to prevent sticking. “If it’s not perfect, we’ll do it a fifth time,” says co-owner Justin Lim. “It’s very tedious and time consuming, but the customer can tell the difference between fresh noodles and packaged noodles.” The packaged product of choice across the U.S. is Sun Noodle, a Hawaii-founded Japanese-noodle and wonton manufacturer that churns out roughly 230,000 servings per day—50,000 of which come from a facility in Compton.

Photograph: Stephanie Breijo

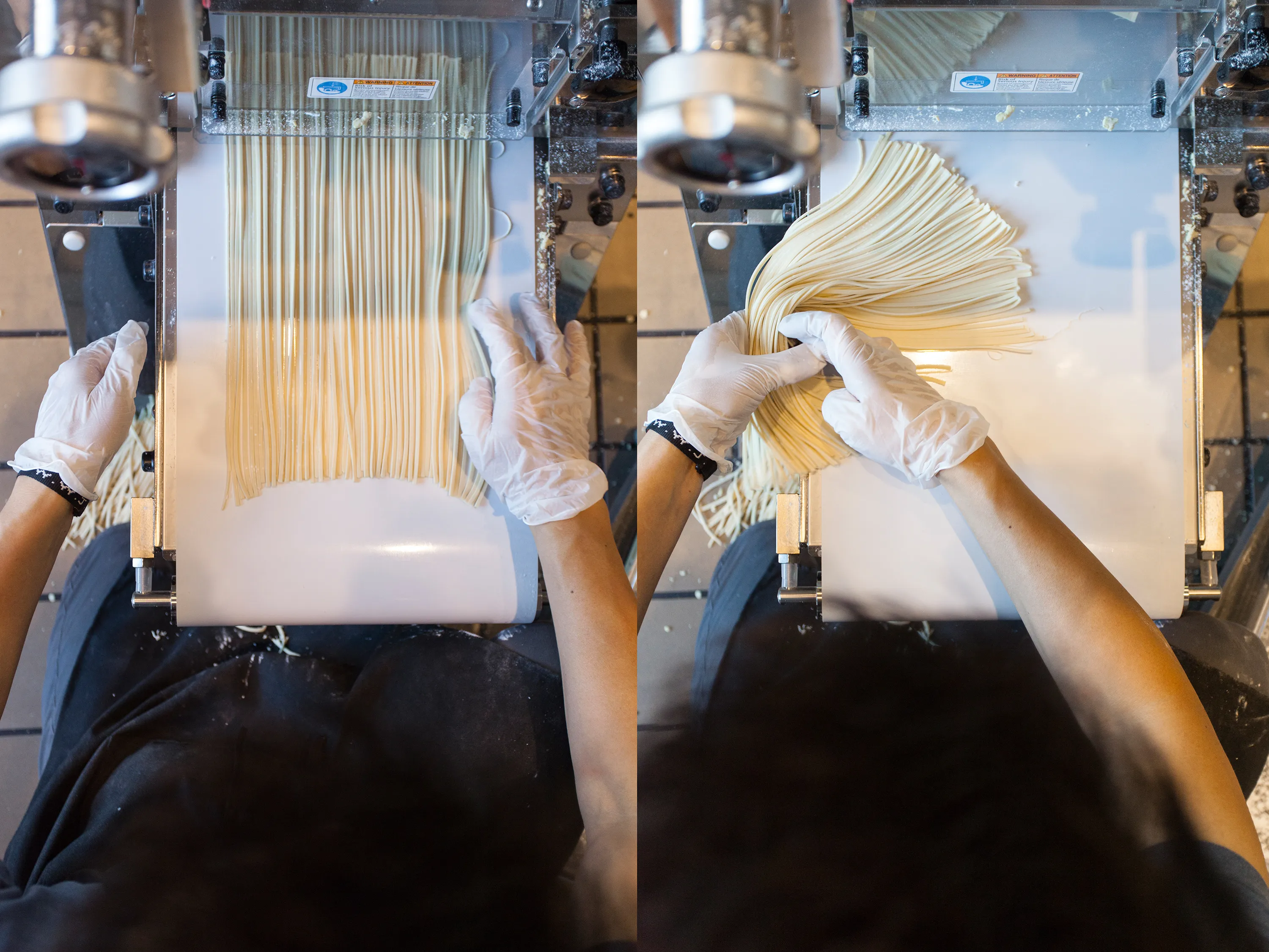

At Okiboru, the team small-batches by hand. After the rolling process, the dough chills for at least one hour before getting cut to the measurements set for either style Okiboru serves. The noodles slowly roll out onto a conveyor belt, a hand deftly swats each serving away and then rolls it into a small tangle, where it then ages for one day if it’s for tsukemen, and for two days if it’s to stand up to a soak in the restaurant’s shio broth.

Of course ramen isn’t noodles alone; the meaty, congealed tsukemen dip takes three days to simmer to perfection, a blend of pork bones and bonito that’s poured over a few morsels of pork for a meaty, textured, hearty soup. Tsukemen toppings range from the more unusual chasu pork ribs, which brine for a day before braising four hours and getting tossed on the grill, to a simple soft-boiled egg with house-pickled radish. The ramen’s broth, a chicken-pork blend, is clear and a lighter option, though for those looking to go even lighter, the team devised a vegan tsukemen made from puréed mushrooms and other vegetables, which still manages to cling to those house-made noodles.

“A lot of places have great noodles without making their own—we just chose to do things the harder way. It really does make a difference though,” says Park. “It’s literally just been batch after batch after batch for a few years, just trying to perfect it all.”

Catch a few more behind-the-scenes glimpses here, then stop by for a bowl:

Photograph: Stephanie Breijo

Photograph: Stephanie Breijo

Co-owner Justin Lim rolling the dough

Photograph: Stephanie Breijo

Photograph: Stephanie Breijo

Photograph: Stephanie Breijo

Photograph: Stephanie Breijo

Okiboru is now open at 635 N Broadway, with hours of 11:30am to 3pm, then 4:30 to 8:30pm Monday to Thursday; noon to 3pm, then 4:30 to 9pm Friday; and noon to 9pm Saturday.