Coming to the Donmar after an off-Broadway premiere, Mike Lew’s play is kind of a kitschy high-school Shakespeare rewrite in the vein of ‘Ten Things I Hate About You’, where teen rivalries blow up on a scale that makes the Renaissance machinations of the Borgias look like games of tiddlywinks. Kind of. Because where those teen flicks used adolescent drama to freshen up Shakespeare, Lew uses his setting to argue with it.

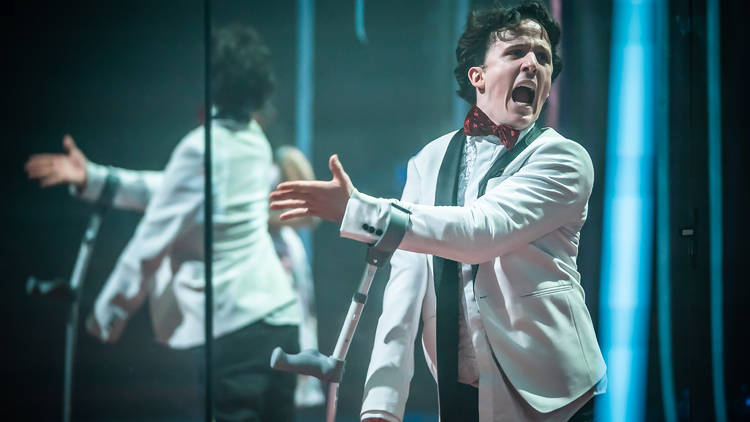

In ‘Teenage Dick’ he takes Shakespeare’s historical hatchet job ‘Richard III’ and questions why this king’s disability and murderous urges are so inextricably linked. Was it actually the cruelty of everyone around Richard that made him long for power? Disabled actor Daniel Monks plays Dick, a teenager who wants to be elected to school council and settle his score with bullying jock Eddie (Callum Adams). Monks’s powerful, detailed central performance is full of internal conflict: yes, he pores over Machiavelli’s strategies in class, but the ambition that burns in him is mixed with vulnerability, and a sharp eye for the hypocrisies of the well-meaning but patronising teacher Elizabeth (Susan Wokoma).

To complicate things, Lew gives Dick a sidekick, wheelchair-using Buck (Ruth Madeley), who is entirely well-adjusted and has learned to find a degree of enjoyment in the teasing that Eddie throws her way.

Lew also inserts a tortuously messy teen romance into the heart of the story. In Shakespeare’s play, Lady Anne is relatively peripheral; the noblewoman Richard woos then discards on his Machiavellian path. Lew wants to flesh her out, so he merges her with a more vigorous character, Lady Margaret, to make her Anne Margaret (Siena Kelly), a girl whose high-school popularity conceals ambitions of her own – she wants to escape to dance school. She dates Dick in secret, then the two take things out into the open in a bravura dance sequence that bursts with limb-hurling joy.

Things don’t stay optimistic for long. Lew’s grim storyline for Anne Margaret slightly destabilises this play’s third act; it’s extremely nasty, in a way that’s perhaps disproportionate for a play that gets rid of most of Shakespeare’s most violent flourishes. For a moment, ‘Teenage Dick’ threatens to become something else entirely, something that punctures American religious conservatism in a way that Hollywood never would. Then it pulls back. But unlike the case with a teen movie, normality can’t ever be restored.