Polish sci-fi legend Stanisław Lem always grumbled about how the film adaptations of his masterpiece ‘Solaris’ – that’s Tarkovsky in 1972 and Soderbergh in 2002 – ultimately failed to convey the sense that the eponymous sentient planet was the story’s main character, the role he felt the inscrutable living ocean played.

Exactly the same criticism could be levelled at David Greig’s new stage adaptation. But I’d hope Lem could acknowledge the boldness and, ultimately, the beauty of Greig’s take on his seminal space novel.

It is the future, and human psychologist Kris Kelvin (Polly Frame) has just arrived at the research station that hovers in low orbit over Solaris, a recently discovered planet covered by a strange, shapeshifting ocean. Snow (Fode Simbo), a scientist, freaks out when he sees Kris arrive; eventually, he tells her about the mysterious death of his crewmate and her friend and mentor Gibarian (Aussie star Hugo Weaving, in fine pre-recorded form for this co-production with the Royal Lyceum Theatre Edinburgh and Malthouse Theatre Melbourne).

All of which Kris could take: but what pushes her over the edge is the impossible appearance of Ray (Keegan Joyce), her ex-boyfriend, who cannot possibly be here.

There is so little sci-fi on the stage that it would be fair to call Greig’s ‘Solaris’ a reasonably faithful adaptation in terms of incorporating the nuts and bolts of the novel, whilst also being a fairly hefty departure in terms of the detail and meaning. The fact that Kris was male in the book is only the most cosmetic of the changes: Greig has lightened the tone, made the other two scientists (Simbo’s Snow and Jade Ogugua’s Sartorius) relatively sane by comparison to their on-page counterparts, and ultimately significantly tinkered with the meaning of the planet and its actions.

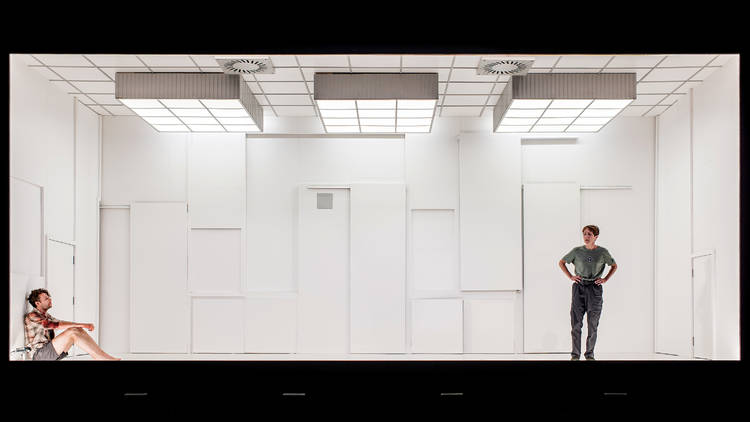

None of this diminishes the power of Matthew Lutton’s starkly beautiful production, which takes place in a series of short, terse scenes delineated by the shuttering screen of Hyemi Shin’s subtly shifting set (there’s some spectacularly nimble stage management from Kiri Baildon-Smith). It’s defined by Paul Jackson’s exemplary lighting design, which conveys the disorientating otherness of the intertwining light of Solaris’s two suns, one red, one blue.

The story is emotionally rooted in another binary – the complicated relationship between Kris and Ray. Frame and Joyce wax and wane in line with each other: at first she is horrified by him, while he is blithely oblivious as to the strangeness of the situation. But the longer she spends in Solaris’s eerie glow, the more she sees this strange recreation of her lover as a chance to atone for her past; he, meanwhile, becomes increasingly distressed as his self-awareness grows.

Ultimately, Greig seeks to tell a more conventional version of the tale than Lem did. He compensates for the essential impossibility of depicting Solaris on stage by making it more explicable, neatening and simplifying it, changing its implications. Occasionally I felt like Greig had lost his nerve a bit, failed to trust the book and made alterations that bring his ‘Solaris’ more in line with a Western sci-fi convention that Lem was never connected to. But perhaps this is just a testament to the original story, in that it can exist in various iterations, each telling us something different about our place in the universe. Either way, it’s a haunting trip, into inner and outer space.