No one writes plays quite like Tom Stoppard, as Nina Raine’s revival of 2006’s ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll’ reminds us. They demand the same close attention, philosophically and theoretically, as Shakespeare. But the sweep of their intellectual terrain can draw you in as surely as something more overtly emotional.

The play spans decades, taking place between the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the Soviets following the Prague Spring of 1968 and the Rolling Stones playing a post-Velvet Revolution Prague in 1990.

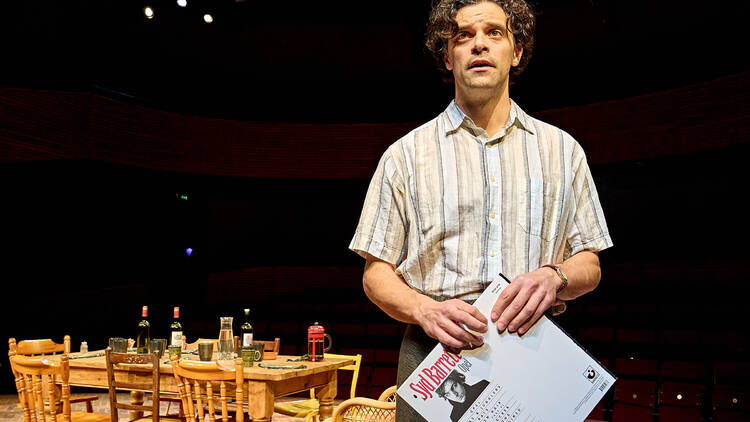

Czech PhD student Jan (Jacob Fortune-Lloyd) returns home from the UK after clashing with his Cambridge University professor, dyed-in-the-wool communist Max (Nathaniel Parker), over the tension between communism and socialism. As history unfolds, Jan learns that ‘evolution’ and ‘compromise’ twist and turn in their pairing. This production’s performance space runs down the middle of the audience, literally dividing us into two sides in a neatly embedded irony given the play.

Rock ‘n’ roll – in the records that Jan smuggles into Czechoslovakia, which are ultimately smashed to pieces by the authorities – is threaded through the play not simply as West versus East, but as politicised self-expression. Among the uncompromising clash of conformity and dissidence, which fuels many of the characters’ arguments, the long-haired opt-out it represents is dangerous. Via legendary Czech group The Plastic People of the Universe, Stoppard debates identity and nationhood.

As Jan, Fortune-Lloyd captures his character’s younger confidence in a way that seems naïve but not glib; and he ages convincingly into a more cautious, but still hopeful older man. Parker has the trickier job of giving us a man who only really changes with frailty. He’s ideologically stubborn. And it feels too easy for someone cloistered in Cambridge to champion absolute convictions. But Parker resonates righteous anger in a way that feels gutting.

The rest of the cast ensures that the orbiting characters still have their own centres of gravity. The women in Stoppard’s plays can sometimes be treated simply as wordy sex objects. But Nancy Carroll, as Max’s wife Eleanor and, after the interval, her daughter, Esme, is a force. As Eleanor succumbs to cancer, her anger at Max’s inability to speak in bigger terms than mechanistic theory is chastening. A classics tutor, she shows the limits of his ‘now’.

The start of Jan’s story is entwined with Stoppard’s own, as a fellow childhood Czech émigré. However, this isn’t a biographical play. As the ideological conversations build and break over the years it spans, and cast members swap out one character for another, it’s really the story of a relationship – the fragile, often fraught one we have with our own beliefs. Raine finds the vulnerability in the long scenes of people arguing about ideologies. Her decision to show the characters dancing to the music in the twilight lighting of scene changes is cathartic.