[category]

[title]

Review

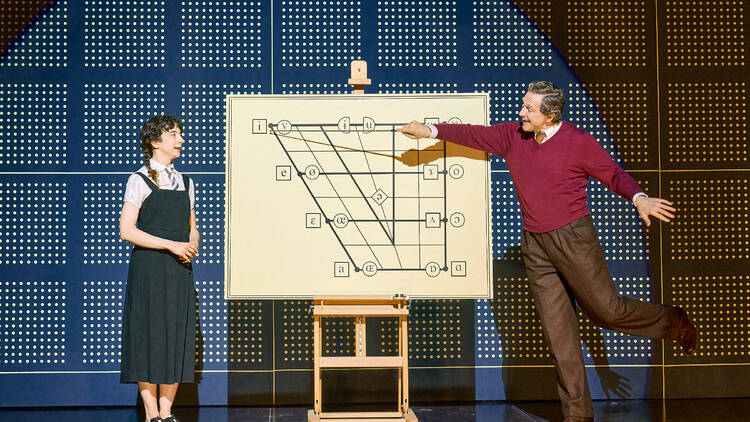

It’s like Jones has put ‘Pygmalion’ under a magnifying glass and we’re all examining it. He’s not really changed it and he’s not casting any particular value judgement, he’s just enlarged the whole thing, so that what was once light comedy has become broad farce. There’s barrelling, discordant piano music bringing a frantic mood to each scene change, and a cold, not-quite-real set by Stewart Laing of pink pegboard, with doors that open and slam shut with great regularity.

Then we’ve got two amazing actors giving two very different, very detailed performances. The more obviously brilliant one is Bertie Carvel as a nerdy Henry Higgins. Knees cocked, hips thrust forward, it’s like his brain is so permanently immersed in thinking about vowel sounds that he barely remembers to hold himself upright. He’s completely unpredatory, possibly asexual, but still a nasty bully so dedicated to phonetics that he doesn’t notice or care about the people around him. Carvel’s eyes gaze at some middle distant spot when he speaks, and he rarely makes eye contact with anyone else. His whining voice is sibilant, almost adenoidal, his brown suit like some ’70s lab assistant. It’s like the polar opposite of his legendary take on Trunchbull in ‘Matilda’, but on the same cartoonish track.

Ferran has drawn the shorter straw. So magnificent in her previous stage roles, including when she stepped in with two weeks' notice to play Blanche Dubois in ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ alongside Paul Mescal, she has a harder time showing off just how good she is here. First half Eliza is all broadness: the loud wailing, the elongated Cockney vowels, and in this magnified production she uses big, scampering movements to create a comic urchin girl who’s constantly trying to hold onto her dignity amid the humiliations thrown at her by Higgins.

But as the play goes on, she takes on an increasingly dominating quality. In the final scene as she and Higgins battle it out, he remains preposterous and conceited while Ferran seems to figure out Eliza at the same moment as Eliza does, becoming a tower of self-possession. It’s an amazing thing to watch. There’s a wonderfully level performance from Sylvestra Le Touzel, too, as Higgins’s mother – the only vaguely normal human being in the show.

Jones has everyone moving constantly around the whole stage, so the production always looks busy, ants under a magnifying glass. But he’s doing to ‘Pygmalion’ what Higgins does to Eliza: treating it like an experiment. We’re left with an exercise in ‘Pygmalion’ which, for all its detail, forgets about the heart, the humour and, crucially, the humanity.

Discover Time Out original video