Bear Ridge Stores is out of chicken. Well, technically, it’s out of everything – but Ed Thomas’s play is all about the gentle fictions its Welsh owners rely on, as they fight off loneliness on the edge of a post-apocalyptic wasteland.

Rhys Ifans spends most of this play stomping about in a blood-spattered apron, periodically accenting his frustrations with the jab of a meat cleaver; but the underemployed butcher he plays is tender, not violent. John Daniel is deeply in love with his wife Noni (Rakie Ayola), who has an almost mystical ability to calm him. Together, they escape reality down the corridors and remembered contours of the shop’s glory days. Thomas’s offbeat, Beckettian dialogue movingly itemises the tiny things that people in crisis hold on to: Noni’s cupboard of trinkets, John’s carefully preserved trousers, woven through with the memories of more normal days.

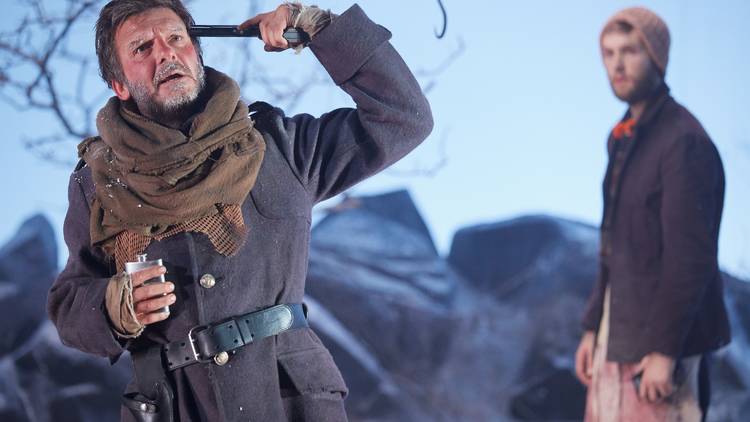

Beanie-wearing slaughterman Ifan William (Sion Daniel Young) periodically interrupts this couple’s reveries, taking the place of the son they’ve lost. And then The Captain shakes them even further out of their world; Jason Hughes plays a hard-bitten military man, forever brandishing a pistol, and traumatised by his role in a war we never quite see.

‘On Bear Ridge’ has odd moments of violence but it’s really almost impossibly tender. These are very, very nice people, guardians of goodness and of a nonspecific time and place where the ‘old language’ was in every mouth, where community was everything, where insularity and acceptance of difference cheerfully co-existed round the same warm fireside. Outside, unseen armies rampage and snow falls hard on jagged rocks. Inside, any moments of conflict are glossed over with a cheerful ‘No, you’re alright, no problem’.

Maybe there’s something a little too easy about this dichotomy, and something a little too sweetly nostalgic about its portrait of ‘the old ways’. But Vicky Featherstone’s haunting production also feels like a fairly explicit conversation with the stories we tell ourselves in times of crisis, and an attempt to show that, in an increasingly reactionary society, nostalgia can be progressive as well as regressive. Its cinematic staging creates a gloriously detailed shop-world that’s gradually dismantled, piece by piece, to leave only desolation. There’s nothing much new about this lament for lost rural identity, but it seeps into you like warm blood seeping into the grain of a worn wooden chopping board.