Though the title could only have been more zeitgeisty if it had been called ‘Snap Election’, this short (45min!), experimental new play from Simon Stephens has absolutely nothing to do with current global sabre-rattling, or, indeed, nuclear war in any obvious sense.

In fact it’s impossible to definitively say what 'Nuclear War' is about: though Stephens is one of our nation’s biggest playwrights – his ‘Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time’ is still ensconced in the West End – he’s often one of our most leftfield, sheer prolificness enabling him to balance the bigger stuff with oddities like this.

By the author’s own description, ‘Nuclear War’ isn’t so much a play as a text designed to stimulate collaboration from a director and her creative team. There are no named characters, but Imogen Knight – a regular Royal Court choreographer making her directorial debut – has chosen to interpret it as being about a woman – played by Maureen Beattie – who seems to be dazedly wandering around London, looking at once familiar things anew. I thought it was probably about a divorce – she seems to talk with a mix of anger and sorrow about a man in her past whose child she had – but it’s so abstract I guess it’s up to you, really.

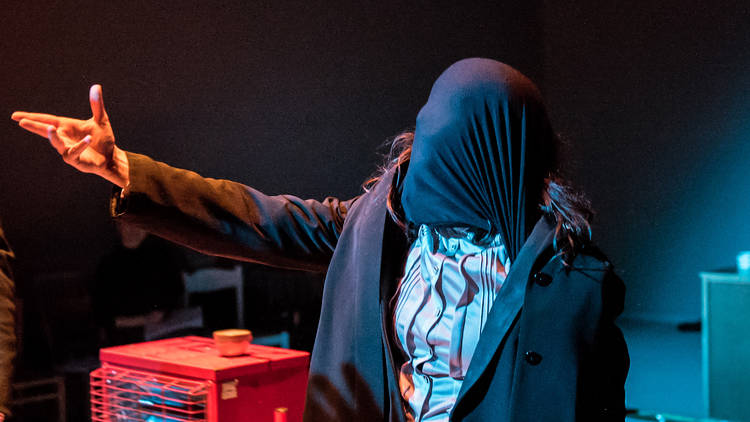

It is, as is intended, very heavily directed. The four other cast members surround Beattie like an insouciant Greek chorus, whispering things ominously at her in a series of stylistically divergent vignettes. Some moments are extraordinary: the bits where the chorus dance and flail with abandon to Elizabeth Bernholz’s hard techno score reminded me of pioneering electro band The Knife’s wondrous last stage show; Lee Curran’s lighting is beautiful, particularly the moment in which all colours apart from black and yellow are drained from the room. But it’s telling these are wordless bits – Stephens’s text often feels drowned by directorial detail and technical trickery, the need to embellish every sentence with a movement or a pre-recorded vocal or a lighting cue. There are moments of gold and moments where it feels over-collaborated with, where it would have been nice to dial everything down and let the text breathe a little. It’s worth pointing out that I saw it at final preview and changes are likely, but I can’t imagine it’ll alter the fundamental nature of the piece.

‘Nuclear War’ feels like a show that revels in its nature as an experiment, happy to not be the finished article, in a constant state of fission – often that's a thrill, but sometimes it feels like a cop-out.