What lies between probability, proof and faith? That’s the provocative question at the heart of writer and comedian David Baddiel’s debut play ‘God’s Dice’.

Henry (Alan Davies) is a physics professor at Exeter University. First-year student Edie (Leila Mimmack), a Christian, asks why she shouldn’t believe in God, if he wants her to believe in the unprovable far reaches of quantum theory. Intrigued, he devises an equation for turning water into wine. Then Edie discovers a factor that she calls the God Constant. This leads to Henry writing a bestselling book, ‘God’s Dice’, which explores the probability of miracles and turns his life wrenchingly upside down.

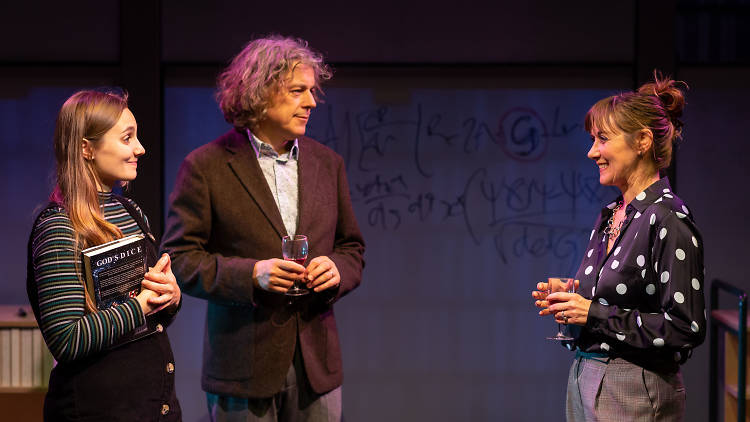

Baddiel reels in some fascinating ideas with dry humour, pitching science and religion as seductively – if superficially – similar to those who are looking for ‘evidence’ to fit what they already believe. Henry (Davies on bumbling, affable form with perfect professorial hair) is naively unprepared for how easily probability is taken as proof.

The irony of Henry becoming the reluctant messiah of a new religion, led by Edie, uncredited co-author of ‘God’s Dice’, is laid on with a trowel by the end. This heavy-handedness aligns with the play’s many lecture-style debates of the same issues. Director James Grieve keeps things moving, but colourful video projections of equations spiralling fluidly off the set’s sliding walls don’t obscure the play’s often talkily static nature.

Baddiel also targets modern online mob culture, as acolytes of ‘God’s Dice’ subject Henry’s wife, Virginia (Alexandra Gilbreath), a writer on atheism, to horrendous abuse. In these later scenes, Gilbreath breathes shell-shocked life into a character that spends too much of the first half just as the antagonistic opposite of Edie.

Mimmack brings a compelling, inscrutable quality to Edie, sharpening to a point the script’s eloquent rebuttal of the ways Christians are habitually dismissed. She holds her own against Henry’s sleazy colleague Tim (Nitin Ganatra), when he pressures her into going for a drink. Which is why her story arc – a dark riff on Henry’s glib address to us at the start about killing yourself to win the lottery in the multiverse – feels like a cheat. It’s one thing to lament the lack of nuance in public conversation today and our refusal to see that situations are often complicated. It’s quite another to put these words in the mouth of a creep like Tim and then turn Edie into a glazed-eyed fanatic to prove him right. It leaves those dice feeling loaded.