Ibsen’s 1873 drama, never before seen on an English stage, is epic in every sense. Charting the rise and fall of the fourth-century Emperor Julian, who attempts to return the Roman Empire to the religion of its forefathers, it pits paganism against early Christianity, and finds both cultish, fatalistic and brutal.

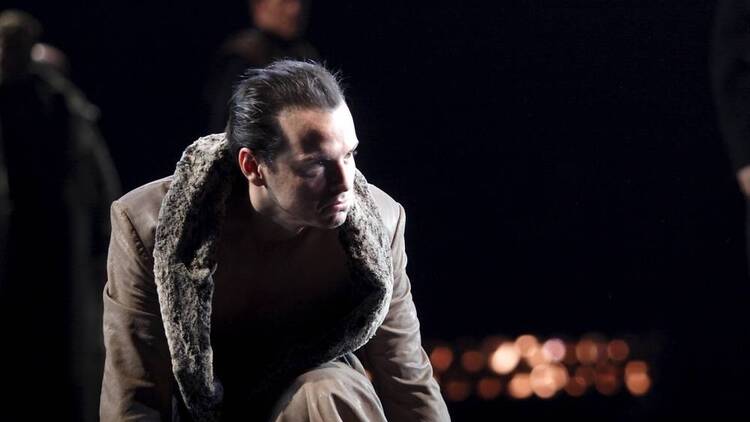

In one indelible image, Paul Brown’s superbowl set is sliced in three. Above, Christianity: a saintly woman’s miraculously healing coffin. Below, the dark charnel house of paganism, where a Mephistophelian shaman (an excellent Ian McDiarmid) searches for omens in a mess of flesh. Trapped between these visions of death, an utterly transfixing Andrew Scott oscillates maniacally as Julian, attempting to find truth and life.

Ibsen’s play is also, magnetically, a quest for selfhood. Scott heroically charts Julian’s progression from tortured Christian subject to hedonist scholar to martial, pagan ruler, and his final descent into paranoid self-delusion is horribly compelling. But despite Scott’s virtuoso turn, and the potent support of a 50-strong ensemble, this production’s pleasures remain extremely strenuous.

Terse and yet grandiloquent, trimmed in half to a muscular three-and-a-half hours by Ben Power, it nevertheless feels both overly long and occasionally lacking, particularly in conveying the allure of paganism.

Jonathan Kent’s modern-dress staging is as bombastic as his material, the Olivier’s revolve has rarely been so stupendously employed, but moments of oddity intrude: pagans trickle past like tired hippies, splattered in luminous paint, and Nina Dunn’s video projections can rankle, tanks and helicopters accompanying a soldier’s halloo to a troupe of elephants.

Anyone interested in Ibsen, though, must go: vast in its ambition, bewilderingly brilliant and undeniably flawed, there is greatness even in its failings.