Nobody goes to a debbie tucker green play to have fun.

And though it has a few dark laughs, her latest, ‘eye for ear’, is absolutely not fun: something you could probably have worked out from the running time alone, a tasty two hours 15 minutes, with no interval. As with most of the capital letter-phobic Londoner’s work, it is very good, though.

Following a prologue, of sorts, in which the large cast can be dimly discerned in the glowing purple box of Merle Hensel’s set, ‘ear for eye’ settles into its lengthy part one. The box lifts, and the majority of the show’s cast sit down on a crescent of chairs. They are all black, and for the next hour-and-a-quarter we see vignettes and monologues in which they talk directly and indirectly about their experience of police racism. The opener sets the tone: a grimly absurd dialogue in which a mother (Sarah Quist) tries to talk to her son (Hayden McLean) about how to carry himself in a way the police won’t find provocative (the Kafkaesque answer is that naturally there is no way).

Although tucker green isn’t one for over-exposition, the short scenes seem fairly apparently to be largely rooted in America and the age of Black Lives Matter. Again and again, characters talk about the humiliation and helplessness they’ve felt at the hands of police who’ve detained them without charge. They discuss activism, and row fiercely over the ‘correct’ way to resist. Parents and elders are repeatedly unable to offer the young advice on how to stay safe. Scenes first performed with American accents are semi-reprised with British ones. There is some light, some humour, some contrast in the textures, but it is a tough, even draining chunk of theatre, and is intended to be. I can only speak as a white member of the audience, but it felt like it offered some insight – no matter how fleeting – into the underlying existential discomfort of living in a society that’s essentially hostile towards you.

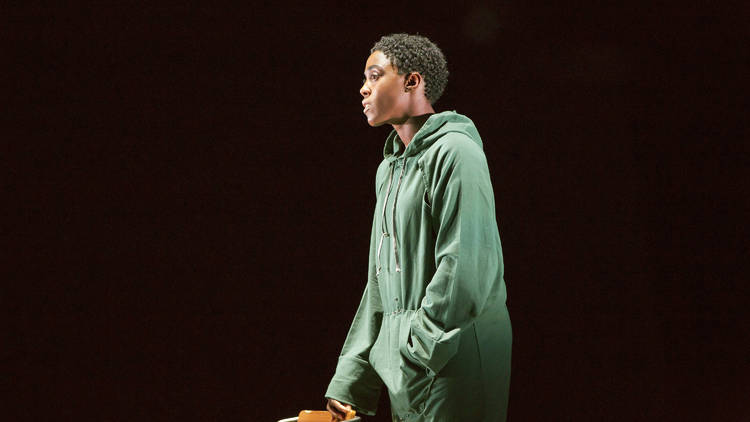

It’s a jolt when eventually the box descends from the ceiling again and a projection tells us that the second part is here. It’s a sardonic two-hander in which Demetri Goritsas’s shrill, needy white man (presumably some sort of academic) pompously ‘discusses’ American mass shootings with a younger black woman, played by Lashana Lynch (possibly a student, though it’s not important that their relationship is unclear). Using every boorish while male trick in the book, he seeks to undermine or cut her down at every turn. As the short scenes – set on a revolve – progress, the two get no closer to having a decent chat, but he becomes more volatile and she becomes more exasperated. Around midway through she is cut off before she can quite get out what’s clearly the key observation of the sequence – that all these killers were white, and that this is never considered as part of their mental pathology, whereas it clearly would be if they were black. He is completely blind to this, literally unable to comprehend the point she is trying to make.

Part three is a pair of short films, one of which features white Americans reading out segregation-era legislation concerning the separation of whites and non-whites, the other of which has white British people reading out the jaw-droppingly racist slave laws of imperial Jamaica.

Though she really isn’t one to spell things out, it’s apparent that tucker green has a thesis: that American and British societies were founded on the idea of black people being the other to a white mainstream, and that this remains the case.

What’s endlessly impressive about tucker green is how her arty side stops her politics ever feeling too on-the-nose, and the centrality of her politics stops her arty side getting out of hand and indulgent. Her new play is a monolithic and painful thesis about the black experience, but it’s also an intensely smart piece of theatrecraft. Its three components would make total sense in isolation; together they interact in a subtly devastating dance.