About the most boring thing you can say about Mark Rylance is that he’s the greatest actor of our age, a fact so irrefutably established by his superhuman turn in Jez Butterworth’s ‘Jerusalem’ that his 2016 Oscar for ‘Bridge of Spies’ felt faintly extra, like giving an astronaut a little certificate saying ‘well done for going to space’.

What distinguishes Rylance from his peers is that he is an unrepentantly eccentric individual. While that has led to him saying some dubious things – Google his name and ‘distilled garlic solution’ if you dare – it’s absolutely fascinating to see where his mix of capriciousness and industry clout takes him when he’s not occupied with Shakespeare, Spielberg or revivals of ‘Jerusalem’.

Last time he appeared in a drama at the Harold Pinter, it was ‘Nice Fish’, a strange and amusing play he’d stitched together from the deadpan poems of US writer Louis Jenkins. And now he returns with a deceptively bleak drama about nineteenth-century Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweis, the little-remembered godfather of antiseptic hospital treatment.

To be fair, Semmelweis has inspired other works: Ibsen’s monumental ‘An Enemy of the People’ is at least tangentially based on his story. Nonetheless, he remains a relatively obscure figure outside his native Hungary.

At first Stephen Brown’s new play – written after the idea by Rylance – feels like it’s setting itself up as ‘ER’ with stovepipe hats, as we’re plunged into the Vienna General Hospital of the 1840s. Here socially inept, uncultured young physician Semmelweis has his eureka moment: that unwashed hands are clearly linked to mortality rates in a surgical setting, and that handwashing with a chlorine-based solution will greatly reduce patient deaths.

Unfortunately, he has no scientific explanation for his discovery, and in the golden age of rationalist discovery, the great doctors simply refuse to believe a theory that Semmelweis can’t back up to their satisfaction.

Rylance could play a stammering outsider physician in his sleep, but it’s the pitch into tragedy that he really gets his teeth into here. As the play wears on, Semmelweis’s homespun charm and serious-minded devotion to saving lives changes into something more disturbing; a raw, insatiable obsession that clots into incandescent rage with anyone who defies him or disbelieves him.

His mind becomes overwhelmed: he’s not so much a genius as an average guy who has become the custodian of an idea that he simply lacks the charisma or diplomacy to spread.

There’s something of Shakespeare’s great fallen heroes – Brutus, Othello – to the way Rylance tackles the lead role, a man whose energies are ultimately channelled into his own downfall. But there’s also something more disturbing there, an almost horror-like aspect to Semmelweis’s psychological descent, an eerie brokenness that takes hold.

The lead performance is more than enough to elevate Brown’s script, which is solid and poetic but leans into exposition and flashback too much, with an ending that gallops through the story a bit too quickly. It should also be stressed that Rylance is far from alone on stage, with Jude Owusu and Pauline McLynn giving fine tragicomic turns as colleagues of Semmelweis’s, whose lower-key ends foreshadow the doctor’s own.

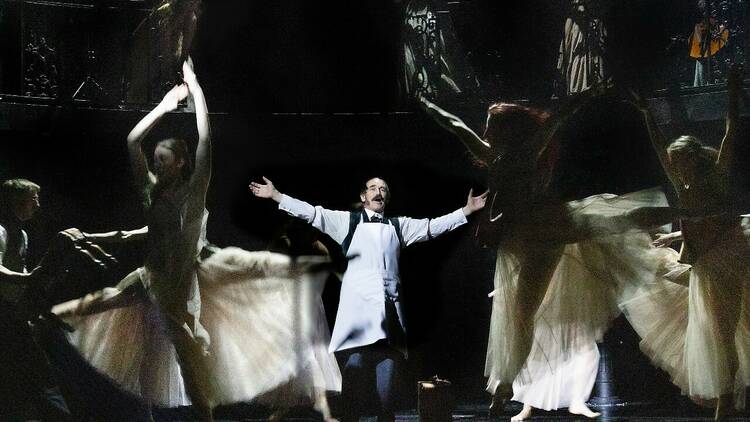

But it’s Tom Morris’s virtuoso direction that ultimately defines the show, even more so than Rylance. In his production the actors are augmented by a grungy all-female string quartet, plus skirted dancers who whirl across the stage like carrion crows taking skittish flight. Absolute fair play to producer Sonia Friedman stumping up for at least eight more performers than the text strictly requires, but it really pays off. Under Richard Howell’s exquisitely moody lighting, Vienna becomes an unearthly phantasmagoria, a blur of bodies and music and collapsing minds, a frenzied dance into the void.