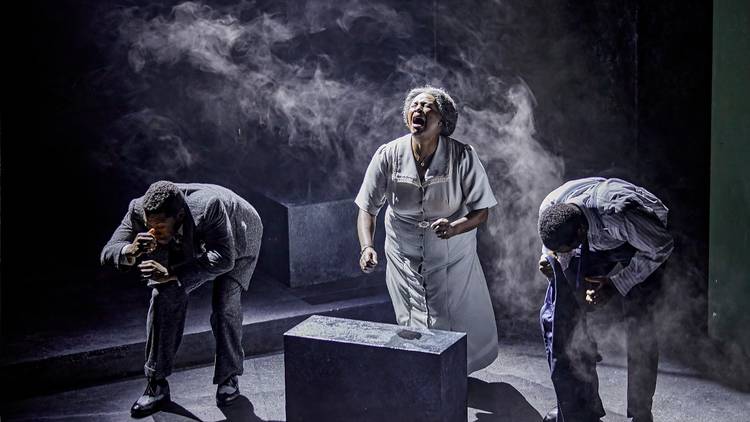

There’s something unsettlingly dreamlike about Marianne Elliott and Miranda Cromwell’s new take on Arthur Miller’s ‘Death of a Salesman’: the furniture of the gloomy Brooklyn house it’s set in is suspended on wires, raised and lowered as jazz melodies float from voice to voice. It’s transferring to the West End after a Young Vic premiere with its biggest stars Wendell Pierce and Sharon D Clarke remaining on board; they’re on incredible form as a married couple whose wistful reveries rarely deliver their promise.

As the title’s salesman, Pierce delivers a performance that captures all the subtleties of Willy Loman’s ballooning moods: puffed out with hot air and misplaced pride, then shrivelled and baggy as reality gets a look in. Clarke has the kind of loyally-supportive-wife role that could barely register; but here, she’s the only solid person in this family, noticing everything, and weighed down with mostly-hidden disappointment in the three men she relies on. The couple’s two sons are convincing, if not quite as memorable; replacing Arinzé Kene as eldest son Biff, Sope Dirisu makes easy-going, faintly bewildered work of this washed-up sports star, and Natey Jones is broad and puppyish as his younger brother Happy.

Despite all the moody atmosphere supplied by Anna Fleischle’s set and Femi Temowo’s haunting music, the first act’s scenes feel a little sitcommy, a little jovial. Perhaps it’s something about the way this family are neatly framed by a proscenium arch, playing out to this chintzy West End space. But Elliott and Cromwell’s taut, psychologically astute approach starts to bite as Willy’s disappointments mount. Instead of retreating into a world of his own, he drags the whole audience into his head, a place where tiny, decades-old disappointments blare like sirens; Biff’s flunked maths test is an epic failure.

A sordid hotel room scene between him and his son could be the stuff of farce (a scantily clad lady hiding in the bathroom, drunk and giggling) but here it’s all tragedy, especially because of the extra dimension this production’s African American central family add. In ’40s America, Willy isn’t just having an affair: he’s having an illicit interracial relationship. When he begs his white boss for his job, his humiliation at having to pick up a dropped package is enormous, almost unbearably painful. And Biff’s failures suddenly make more sense; he’s never been taught the kind of humility demanded of African American men in this discriminatory society.

Despite its often-dreamy pace, these carefully observed moments mean that ‘Death of a Salesman’ has a real urgency to it. A nightmarish momentum that keeps you going through three-plus hours of well-thumbed disappointments.