A few eyebrows were raised at New York playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins' decision to follow up his exhilaratingly weird race satire ‘An Octoroon’ with something that sits solidly in the tradition of the Great American Play – one of those sprawling dramas perfected by Tennessee Williams, where grown-up families rip into each other and painful memories spill out. But 'Appropriate' mixes its time-honoured portrait of a family self-destructing in a Southern mansion with something darker; its rafters creak and disgorge secrets of their own.

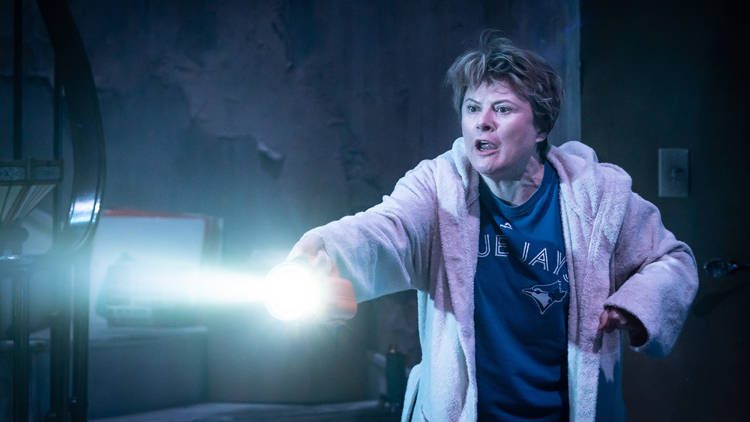

Everything revolves around the Lafayette family patriarch, who is dead. Was he a bigot? Mentally ill? A neglectful father? His children gather to work it all out, as they prepare his clutter-stuffed house for an estate sale. His eldest daughter Toni dominates proceedings; played by a wonderfully bitter Monica Dolan, she's a staunch defender of his legacy as a fair-minded lawyer, even as her two adult siblings give more and more evidence to the contrary.

This a play where things are given shape by the artfully shaded negative space around them. Another invisible presence in this house is the legacy of the African-American slaves who worked this plantation, and the lynchings in the years that followed. There's something deeply ingenious about the way that Jacobs-Jenkins uses an all-white cast to talk about racism. He skewers the Lafayette family as they collude to mask and disown their slave-owning past, subtly suggesting it lies at the root of their sicknesses.

When they find a book full of photos of murdered black people, prodigal son Franz (Edward Hogg) and his wonderfully-drawn hippie fiancé (Tafline Steen) try to clear the air with AA-style therapy speak and lit candles. His serious older brother Bo just wants to sell them. Bo's teenage daughter Cassidy is morbidly obsessed. In 'An Octoroon', Jacobs-Jenkins confronted his audience with a projected image of a lynching; here, he sketches a series of unsatisfactory responses that illustrate the inability of a white viewer to feel the trauma behind these visual records.

Ola Ince's production needles and builds in a succession of agonising emotional confrontations. But the supernatural tensions built into Jacobs-Jenkins' script never quite come to a climax; the screeching sound effects and blackouts between scenes feel like a tacked-on extension to this well-constructed house of ills. Ultimately, the ghosts that linger are the things left unsaid, the truths that every member of this family tries to bury with words and cobbled-together rites.