Would YOU go fascist for Matt Smith?

That’s maybe not the exact moral of German director Thomas Ostermeier’s fabled Ibsen production, now receiving its English language premiere.

But it’s certainly something we’re kind of made to contemplate at one point during this deliciously spikey production’s showstopping central scene.

Ostermeier and Florian Borchmeyer’s modern adaptation of Ibsen’s 1882 classic – in an English version by Duncan Macmillan – sticks pretty close to the original in many ways. It follows Dr Thomas Stockmann (Smith), who determines that the waters of his town’s newly-opened spa are contaminated and something needs to be done about it - which horrifies the great and the good of the town as represented by his desiccated brother Peter (Paul Hilton), the mayor. The problem? In what is vaguely intimated to be contemporary Tory Britain, the town desperately needs the income from the spa – Stockmann’s expensive and time-consuming proposals will likely kill the town’s boom dead.

Ostermeier’s production moves through distinct phases. The cosier first half really mines the comedy in the story, and for whatever reason decides to have Smith’s Stockmann, his long-suffering wife Katharina (Jessica Brown Findlay), feckless local newspaper editor Hovstad (Shubham Saraf) and his shambolic co-worker Billing (Zachary Hart) in a band together, where they knock out a ramshackle version of Bowie’s ‘Changes’.

That the very idea these people are in a band together seems to be dropped therefore feels like a hallmark of Ostermeier’s style. The band feels like a good metaphor for the initial closeness of the community, even if it’s never spoken of again after the first half hour. The director a chucks a lot of stylistic stuff in with more concern for impact than consistency - see also the big live Alsatian that Stockmann’s father-in-law Morton (Nigel Lindsay) takes around with him at all times, an entirely superfluous addition to the text that projects a fun air of absurdity. We often stereotype the artiness of European theatre as being humourless, but most of Ostermeier’s wilder ideas are a hoot.

During the first section, Smith’s Stockmann is a gentle dreamer, a laid-back eccentric who is almost poignantly certain that he’ll be hailed as a hero for getting the spa shut down. Following a series of rude awakenings at the hands of his friends, brother and pragmatic local businesswomen Aslaksen (Priyanga Burford) who owns Hovstad’s paper, he is rapidly disabused.

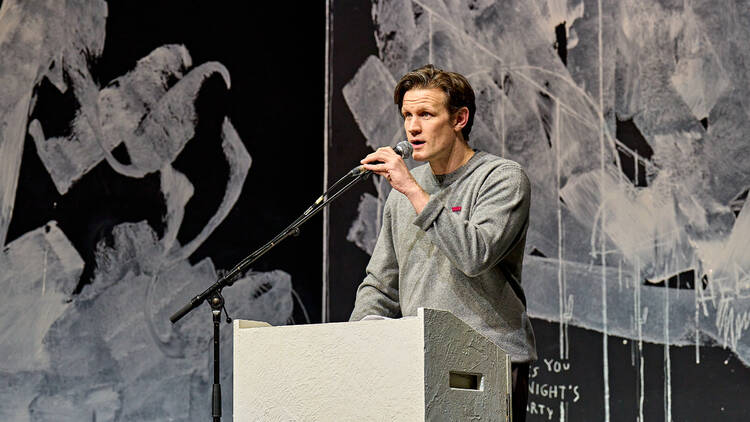

The middle, then, is the production’s most famous bit, as we’re cast as the audience to a townhall debate in which a now furious Stockmann spews out a snarlingly nihilistic rant against Broken Britain -– proper fist-pumping fuck the Tories stuff, until he starts lashing out at the nature of democracy itself and calling for executions. Some of what he says is unfortunately true. Some of what he says definitely sounds pretty darn fascist. Then we’re invited to weigh in.

It’s fascinating. For starters, it feels bracingly direct: Ibsen’s original Stockmann does upbraid the townspeople in a not dissimilar manner, but here roping the audience in as participants makes the shift in the protagonist’s tone much more whiplash-inducing. We’ve gone from a parable about democracy to actually having an argument about it.

Or are we? I was unclear as to what proportion of the audience speakers were actually genuine: after a hesitant start there was soon a sea of hands up, but the relatively well-put-together answers – no losing the thread or asking giggling questions about ‘Doctor Who’ – made me a bit suspicious.

But maybe it doesn’t matter so long as we’re at least encouraged to think of talking points: Ostermeier blows the themes of the play up in the most thrilling way. Screw subtext! Let’s force everyone in the room to have a mini-crisis about the legitimacy of ineffectual Western government!

Of course, it’s not going to mean what it means in Germany, which famously did have a fascist government. But it’s enormously provocative nonetheless.

A deliciously punchy final third sees Stockmann and Katharina reckon with the fallout from his meltdown. It’s hard to exact say where Ibsen starts, Ostermeier and Borchmeyer begin and Macmillan continues, but for a production conceived with the specific backdrop of post credit crunch Germany, it slots immaculately into 2024 Britain, the town’s desperation to save the spa chiming perfect with the recent spate of bankrupt English councils.

It’s also, as I’ve said, extremely droll: Ostermeier and various writers manage to be sincerely provocative with largely funny characters. The lightly absurdist quality means we never really feel like we’re being lectured. Although the ending is very similar to Ibsen’s, a deft final flourish – just a single look between Smith and Findlay – changes the tone to something altogether lighter and more mischievous.

In a fine cast, it often feels like Smith is happy to keep it low-key, a largely charming stage presence who doesn’t attempt to upstage Hilton's insectoid weirdness, the affably hopeless Saraf or the righteous Findlay. The big exception is his town hall rant, which he delivers superbly, a mix of glorious truth-telling and red-pilled douchiness that’ll leave you wanting to high-five him and slap him in equal measure.