[category]

[title]

Review

The year 2002 saw the debut of both the regrettable Star Wars prequel ‘Attack of the Clones’ and Caryl Churchill’s cloning drama ‘A Number’, and I think it’s safe to say there’s not much contest over which one has stood up better over the years

Since its Royal Court premiere – starring Michael Gambon and Daniel Craig! – ‘A Number’ has been restaged endlessly. It’s surely now up there with ‘Top Girls’ as leftfield icon Churchill’s most popular play, with the last production just two years ago at the Bridge.

And the constant revivals feel justified. What was once seen as Churchill’s explicit comment on the possibility of actual cloning – in response to the Dolly the Sheep saga – has deepened and become richer with age and the passage of time, a devastating drama about paternal neglect delivered as speculative fiction.

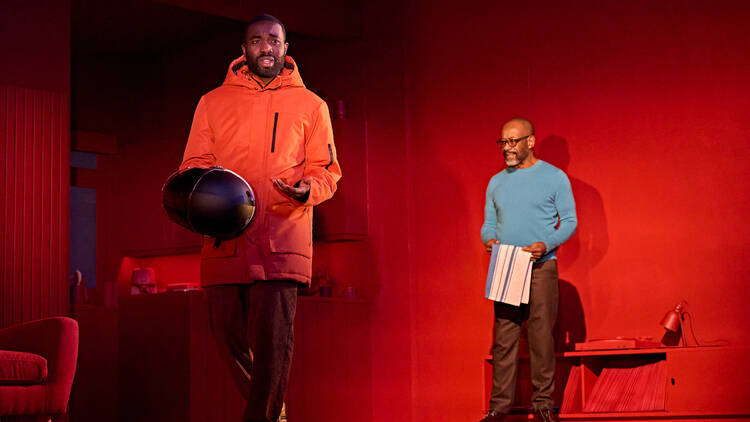

In Lyndsey Turner’s Old Vic revival, Lennie James is Salter, a middle-aged man who we see in a series of encounters with his sons.

Except most of the sons are clones, all played by ‘I May Destroy You’ star Paapa Essiedu. First, we meet the gentle, confused Bernard 1, who has been raised as Salter’s son but has just discovered that he has numerous artificial siblings. He quizzes his dad about it, and is further confused when Salter’s blustering reassurances collapse under the slightest pressure, leading him to eventually receive confirmation that Bernard himself is a clone.

Then we meet Bernard 2: unstable, edgy, and deeply traumatised by his discovery of the existence of Bernard 1, for reasons that become rapidly apparent.

Later, we meet Michael Black, a third version, here a gauche American whose almost supernatural lack of introspection stands in brutally ironic contrast to his anguished brothers.

The clones are a gift of a role to a young actor looking to show their range off. Essiedu is wonderful in all three roles, but especially as the Bernards, two damaged young men who try to resolve their shattered sense of selves in very different ways. It’s not enough to simply show he has range, though: it’s what the Bernards share that makes it a great performance, their vulnerability but shared inability to really process the magnitude of what Salter has done.

Ultimately, though, ‘A Number’ stands or falls on its Salter, and James – in his first stage part in aeons – hits upon a fine interpretation. The role has tended to be filled by patrician white guys with a bit of a low-rent Doctor Frankenstein thing going on, as they manipulate and lie to their ‘children’. But James gives off the sense of an altogether less powerful or scheming man. We learn that the geezerish Salter did what he did through a desire to atone for his past mistakes. And we see him almost physically recoil from the truth when it is presented to him, his bluster crumbling, meekly caving in and agreeing with his sons every time they confront him over some hard truth they’ve discovered. We laugh at his transparent, childish sense of self-preservation. You keenly sense that he’s a man who has always taken the easy way out, always tried to avoid confrontation, never felt the need to stand up for what’s right, and now it’s come back and bitten him.

It would be a mistake to think Churchill wasn’t at all interested in the ethics of cloning when she wrote it (we’ll never exactly know because she never does interviews). But distance from Dolly has liberated ‘A Number’ from current affairs and helped it grow in power as an account of the damage parents do to their children. James’s Salter believed he could wipe the slate clean of his earlier mistakes as a father and simply start again, that this was a chance to redeem himself. But it was all a lie that only served to salve his conscience until such point as his sons understood what he had done.

Turner’s taut production keeps things minimal, with Es Devlin’s box set an apartment painted entirely in a monochromatic, womb-like red, the only point of difference a photo of a schoolboy (presumably Bernard 1, though it remains somewhat ambiguous). Startling quick changes of Essiedu’s clothes and dissonant strings music delineate the scenes. But it’s ultimately unshowy and stark, an epic tale of a father’s horrifying failure compressed into a single hour, dense and dangerous as dark matter.

Discover Time Out original video