When was the last time you danced? Like, properly squeezed yourself into a sweaty crowd, shook off your inhibitions and got down? For me, it was March last year. I was at the Heathcote & Star in Leytonstone. It was around 1am and it involved my whole Whatsapp group screaming ‘I’m horny – horny, horny, horny’ across a birthday cake-covered dancefloor.

It’s been 15 months since that (deeply uncool) moment. And while, during the pandemic, I’ve got drunk, been to (outdoor seated) nightclubs in Tottenham and Brixton and tuned into (live-streamed virtual) festivals, I haven’t danced. In fact, I can’t remember a period of my life where I haven’t done it for this long. Right now, in a normal year, I’d be one of the thousands of Londoners gearing up for a summer punctuated by it: at Pride, at Carnival, at festivals, nightclubs and weddings. But right now things still feel uncertain.

Across the city, culture is returning. We’ve got our art galleries, theatres, cinemas, restaurants and bars back. But dancing at a party is still just out of reach. Sure, we might be able to attend a wedding now, but we aren’t allowed to do the YMCA with the father of the bride. Dance classes are back, but that’s no use for those of us whose skill level only goes so far as throwing our hands in the hair and jumping about a bit. The reopening of nightclubs has been pushed back to late July. A third of UK festivals have already been cancelled.

Moving through time

This might sound trivial to you. You’re maybe sitting there thinking: Why make such a fuss about dancing when so much of our lives is back to semi-normality? Just look at the mess caused by all those illegal raves last summer: woodland littered with tins and balloon canisters, people selfishly putting lives at risk all for the sake of a few hours of fun. Here's the thing though: dancing is actually integral to the human experience.

‘Humans have been dancing for as long as they’ve been human,’ says music and culture writer Emma Warren. Recently she’s been reading a book called ‘Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy’ by Barbara Ehrenreich. ‘She talks about there being lots of images of people dancing in cave paintings,’ she says. ‘But not a lot of people sitting around having conversations. So the things that people chose to represent back then were to do with movement and music.’

It’s hard to think of any culture in any period of history that hasn’t danced. In London alone our history is entangled with the artform. During World War Two dance clubs were seen as community unifiers, morale boosters, parts of the war effort. Newspapers used stories about people continuing to jive even as air raid sirens went off – ‘the dancers continued as though nothing had happened, although many of the windows had been blown out’ – as a way to build Blitz spirit. More recently, dance scenes and night clubs have been born to provide homes for outsiders. ‘Look at the sound system generation,’ says Emma. ‘Black British people who had to requisition spaces because most traditional nightclubs weren't available, for reasons of direct and indirect racism. It was about creating community spaces, safe spaces, and important places.’

The sixth sense

You know that feeling as you walk down a dark club corridor towards a dance floor? You’ve just arrived, everything feels a bit disorientating. You can’t see the DJ yet, the music is muffled, but your heart rate starts going up. It’s like your body is getting ready to dance...

That’s something called sensor motor coupling – the same process that makes you react to a loud, sharp bang by jumping out of your seat – and it’s a biological drive to move to sound. Or at least that’s how Dr Peter Lovatt explains the science of it. He’s a psychologist who has been researching the power of the artform. ‘We have found that when you’re dancing in nightclubs, you’re communicating in ways you don’t communicate in almost any other place on the planet,’ he says. ‘Via hormones and genes that influence the way you dance.’ (The impact of hormones on your dance style is so great that – if you are someone that has a menstrual cycle – the way you dance will change throughout it and the way other dancers react to you will change too.)

To Peter dancing is almost like a sixth sense: a way of understanding and interacting with the world. His work has found that dancing in a crowd is so powerful that afterwards people report liking each other more. They report feeling more similar in terms of aspirations, hopes and values. They trust each other more and want to help each other more. It doesn’t matter what kind of music they’re listening to.

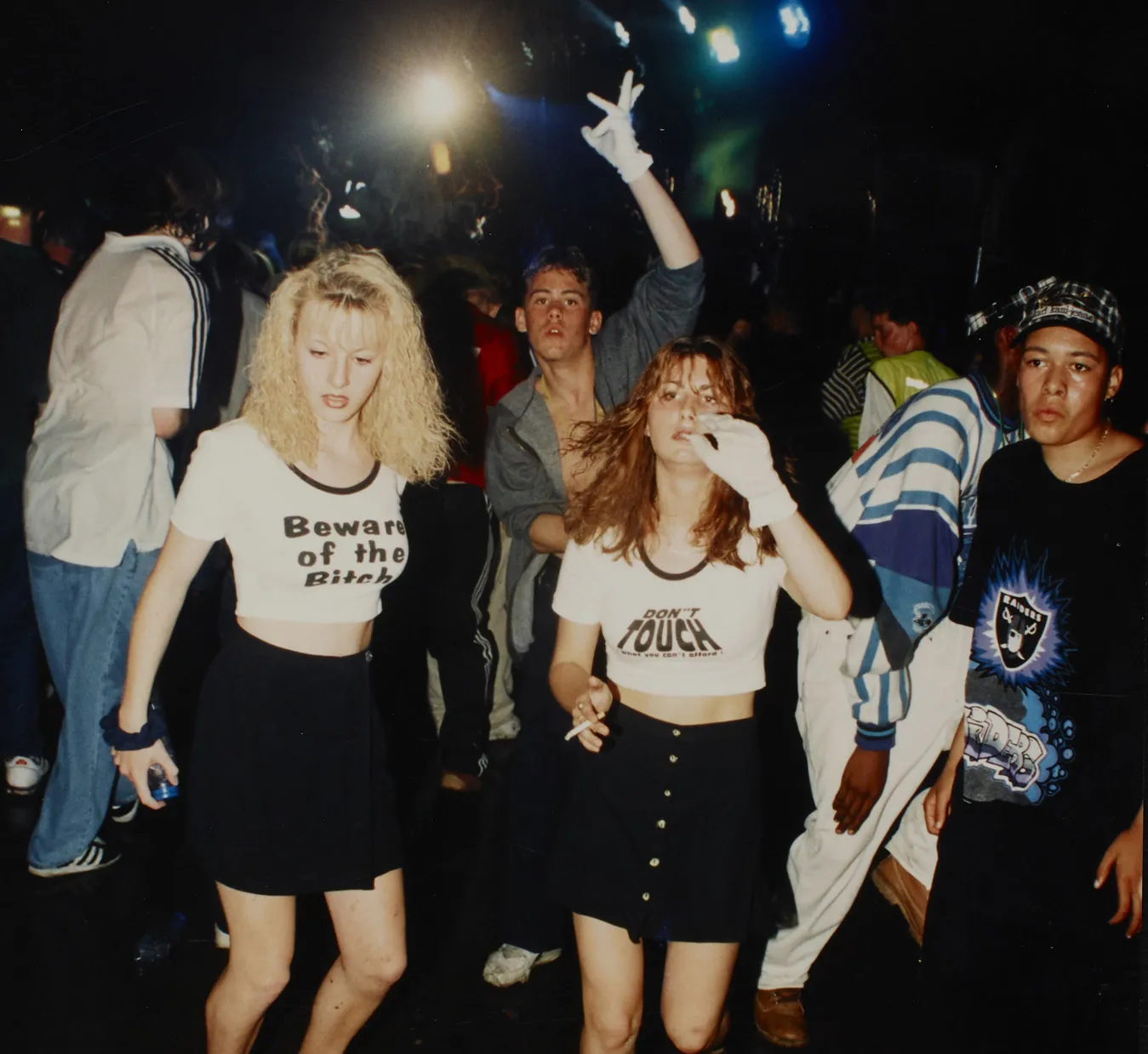

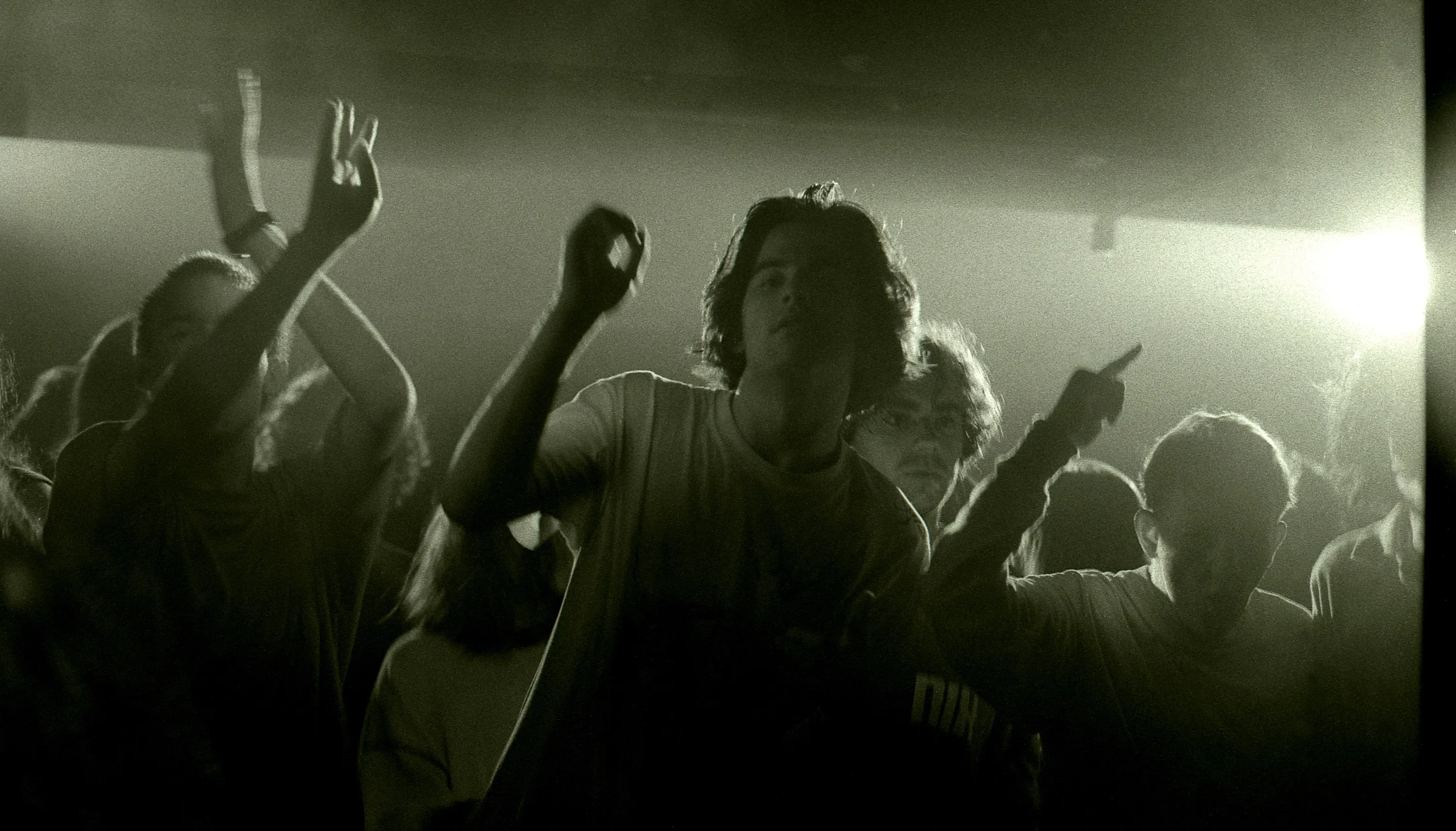

This doesn’t surprise Jamie Brett from the Museum of Youth Culture. For the past few years he has helped build an online archive of photographs of nightlife movements through history. When these pictures are uploaded, they’re organised by tagging them with words like ‘smiling’ or ‘jumping with friends’. Doing that has helped him notice a commonality between them all. ‘You'll start to see a skinhead jumping off a brick wall at a gig, and then you'll see ravers jumping into a crowd,’ he says. ‘And you see a crossing over of these moments of celebration. It's not just a mod, or it's not just a raver. You're seeing the same elation and camaraderie and, you know, togetherness, in different ways.’

Feeling free

Look, I'm not an idiot. I'm not about to risk my life or the lives of those around me so I can go and do my comedy line dance jig to ‘Old Town Road’. I'll wait it out. But lockdown has made me realise the importance of dancing in my life. That it’s not something that I’ll grow out of or just an excuse to stay up too late and get drunk. It’s something I need to feel alive.

‘Nightclubs didn't start just because of some whim or fancy,’ says Peter. ‘They serve a biological and psychological need. You connect with other people, you connect with the music, you're connecting with your own biology. It’s no wonder we feel bad [right now] because we’ve lost a basic human need.’

Studies show that if you strip creative movement from people’s lives their mind becomes dulled, their bodies start to ache, they have less ideas, their mood drops. In a time when so many of us have lost so much control over various aspects of our lives, for me the biggest loss is of the sense of escape dancing offers. Jamie from the Museum of Youth Culture agrees. ‘I think that those transcendental moments that you have in clubs are quite radical,’ he says. ‘You’re taking control of the world that you live in and doing something quite different from your daily life. It’s adding brief moments of complete and utter freedom to your life.’

As we wait for clubs and festivals to return, there is one good thing to hold on to. Have you noticed you’ve had a stronger reaction to music in lockdown? That’s because of the dulled environment we’ve been in, says Peter, and it means that when we are back on the dancefloor it’s going to feel even better than it did before.

‘Imagine somebody took away another of your senses for 18 months,’ he says. ‘And then you got that back again. The world would feel much richer. And so when those clubs open again, we'll have this amazing experience. If we relax and let ourselves go – boom – we'll be back on it immediately.’

All pictures courtesy of the Museum of Youth Culture.