[title]

Just weeks ago London’s streets throbbed with people. Now, silence fills our very empty city. With the capital at a standstill it’s an uncertain time for many London businesses. But, for some of London’s oldest traders, the current crisis is yet another blip on their ancient timelines. Not only have some of its earliest companies traded through the two world wars, they’ve seen off droughts, financial catastrophes and even the city’s other huge pandemic – The Great Plague of London. In these challenging times, we spoke to London’s retail survivors about how they’ve made it through some seemingly insurmountable circumstances.

James Smith & Sons, 210 years old

This umbrella shop has been keeping Londoners dry for nearly two centuries. Its shop on New Oxford Street has been open rain or shine, even through both world wars despite a shortage of steel to make umbrella frames. Phil Naisbitt, the shop manager, tells us about the retail survivor.

‘The huge heatwave in 1976 was the end of a lot of umbrella businesses. The owner said the shop that year was like an empty town in cowboy films, but without even any tumbleweed. We took on a lot of staff made redundant from other companies that year. We took so many that the shop probably had the world’s greatest concentration of umbrella knowledge. It survives because it’s such an enjoyable place to work and totally unique. You can feel the atmosphere of the place when you walk in; it’s somewhere that hasn’t really changed for 100 years. It’s touching history. This is the first time it’s ever had to shut. It's a difficult time, but we’re determined the shop will come through this.’

Borough Market, 1,000 years old

London’s iconic culinary rabbit warren has a sprawling 1,000-year history – it is even mentioned in the Doomsday Book. Over that time it has operated in many guises: a semi-illegal medieval trading hotspot that was eventually closed down by the authorities in 1754 (it reopened two years later), a thriving wholesalers, a declining relic and a living embodiment of London food culture. Managing director Darren Henaghan, tells how the ancient landmark is thriving in the twentieth century.

‘Thirty years ago the place was in dire straits. There was no money in it and the trustees did car boot sales out of the place. It took pioneering celebrity chefs like Keith Floyd to get people looking for lovely fruit and veg. That’s when the businesses here began opening to the public. In the last 20 years it’s become quite something and now we’re a symbol of London. Community has been incredibly important to our survival. When ThamesLink work threatened the market’s future, it was the community that came together to protect it and help launch a public enquiry. After the terror attack [in 2017] it was overwhelming to receive so many letters, some tear-stained, about the part we’d played in people’s lives. Some said they’d proposed to their wife at the market or told their husband they were pregnant here. People have a real affinity to us. That’s why it’s such a privilege doing my job.’

Paxton & Whitfield, 278 years old

Whiffs of cheddar and stilton have wafted down Jermyn Street since 1896 – that’s how long this iconic cheesemonger has been there. But its history stretches back even further, starting off as a market stall in 1742. Nearly 280 years later, it’s still supplying Londoners with top-notch dairy. Managing director Ros Windsor explains why.

‘Our story has had some ups and downs but we’ve hung in there. I think we’ve survived by reacting to our customers and keeping a strong ethos at the heart of what we’re doing: for us that’s quality. It’s about leading rather than following – Paxton’s was selling cheese online before the millennium. You have to be alert to opportunities and adaptable: we had to become a grocer’s shop selling all sorts of different things during the world wars because there were only two types of cheese available. Of course, you need a bit of luck too!’

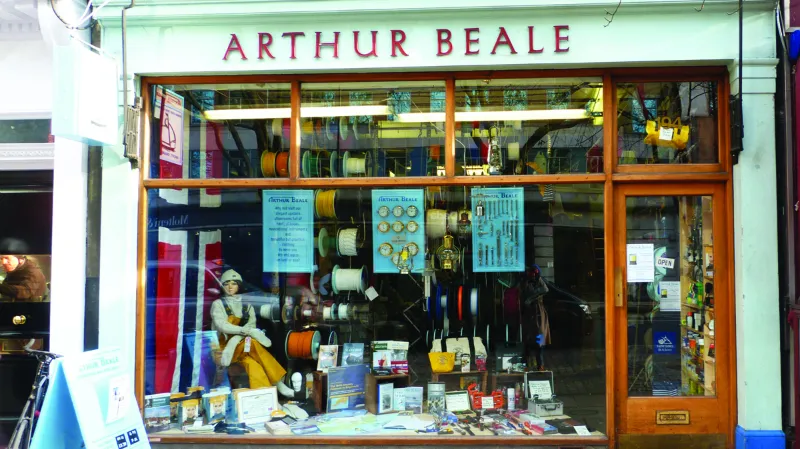

Arthur Beale, 520 years old

Why is there a yacht chandler in the middle of the West End? Well, in 1500 when Arthur Beale was established, St-Giles-in-the Fields was surrounded by actual fields filled with plants used to make ships’ ropes. Over the centuries the shop has made rope for the Alpine Club, as used by explorer Ernest Shackleton, and aerial masts during the world wars before switching to selling boating supplies. Owner Alasdair Flint tells us why, 500 years on, it’s still going in the heart of Theatreland.

‘When they invented nylon in the ’40s, our rope became redundant so we had to adapt. The business shifted to yachting and it was a shrewd move because boating really took off in the ’50s and ’60s. But it didn’t keep up with the times. The last manager kept his books handwritten and we had no website or email. I visited the shop just before it was about to go into liquidation. I’m a very keen yachtsman and was in a position to resurrect it and it’s been a real labour of love. We’ve changed it a lot, but been careful to leave it looking like the old shop it was. Ninety percent of our sales are through the shop, so the current crisis is having a devastating effect. But the shop was already quite old when the Great Plague of London struck. Some of the victims were buried in the church opposite. It got through that one and we plan to get through this too.’

Want to support businesses now? Here's our guide to how to help (and get help) in London during lockdown.

Or consider ordering your groceries locally.