[title]

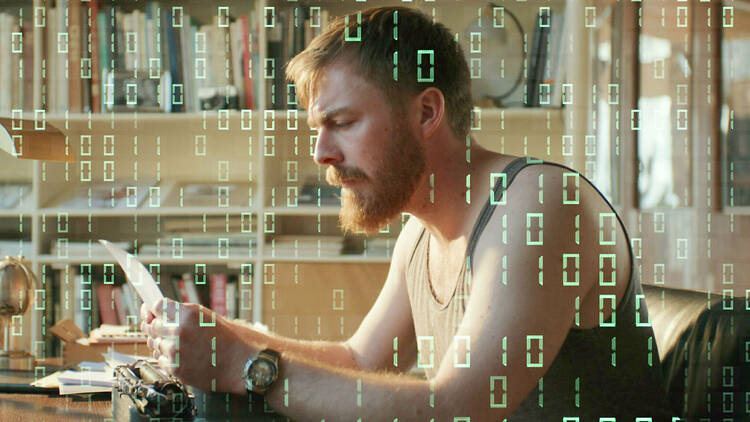

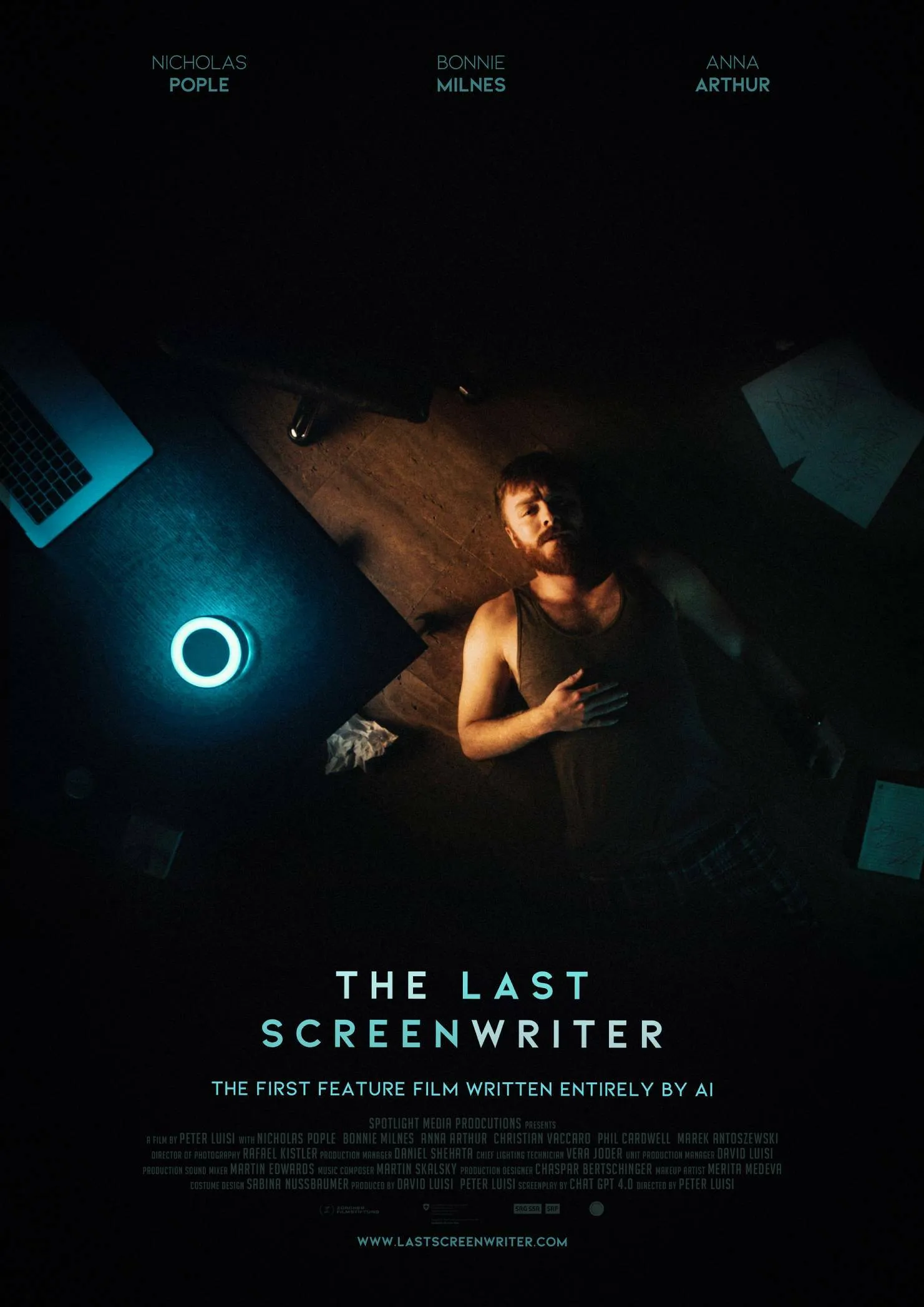

When London’s legendary Prince Charles Cinema advertised a screening of Peter Luisi’s ‘The Last Screenwriter’, billed as ‘the first feature length film entirely written by AI’, the backlash was immediate – and fierce.

After 200 online complaints and outrage from film critics on social media, the programmers announced it was cancelling the privately booked, publicly accessible screening, scheduled for the evening of June 23. ‘The feedback we received highlighted the strong concern held by many of our audience on the use of AI in place of a writer which speaks to a wider issue within the industry,’ a cinema spokesperson said. The announcement acknowledged the film’s experimental nature and its ambition to ‘engage in the discussion about AI and its negative impact on the arts’, but the screening was shelved.

Films being pilloried sight-unseen is hardly a new phenomenon: the BBFC famously received hundreds of complaints prior to the release of Martin Scorsese’s ‘The Last Temptation of Christ’, but not a single one afterwards. Pushback against the encroachment of AI into filmmaking, however, tends to be about the protection of artists’ livelihoods, rather than morality. Marvel endured a backlash for its deployment of AI in the title sequence of Nick Fury-led Disney+ series ‘Secret Invasion’, as did this year’s Late Night with the Devil’, a horror film that included AI-generated art.

The use of AI in screenwriting was a key plank of last year’s Hollywood writers’ strike, although the negotiated settlement – that AI can be used to generate scripts, but writers will always be credited for their work – was a less than optimal solution.

As the debate played out on social media, the inevitable blowback to the backlash followed, with some suggesting that the programmers had given in to ‘the mob’, and that pulling the film was tantamount to book burning. Were calls to have the screening cancelled – to be clear, few were calling for an outright ban – a well-meaning knee-jerk reaction to the idea of the film, without concern for the intentions behind it? An attempt to shut down debate, rather than engage with it? Would people have given ‘The Last Screenwriter’ – and the cinema – the benefit of the doubt if the film was the work of an experimentally-minded filmmaker such as a Steven Soderbergh, Michael Winterbottom or Mike Figgis?

While not exactly a household name in his native Switzerland, Peter Luisi co-wrote the screenplay for ‘Vitus’, the country’s entry for the 2007 Oscars. He’s won nearly 50 international awards, and wrote and directed last year’s ‘Bon Schuur Ticino’ (‘Bonjour Switzerland’), the 8th most successful Swiss film of all time. ‘Being a creative writer, I always thought I am safe,’ Luisi says. ‘Even if I’m paralysed from the neck down, I can still earn my living.’ The arrival of AI, however, gave him pause. ‘Maybe if you’re an accountant or copywriter, you might be worried that AI will take your job, but what if AI gets good at doing my job? Can it write a screenplay?’

Luisi decided to put ChatGPT to the test, imagining that the best way to engage with an unavoidable subject was to face it head-on.

He set himself a series of unbreakable rules. ‘They always talk about AI assisting humans,’ he says, ‘but I thought: what if a human assisted the AI?’ His only input as a screenwriter was to type: ‘Write a plot to a feature length film where a screenwriter realises he is less good than artificial intelligence in writing.’ ‘It couldn’t be a romantic comedy or a spy film,’ he explains. ‘It had to be meta in its engagement with the subject matter. To me, that – and my non-interference rule – was the only way to ensure legitimacy for the film and the experiment.’

As ChatGPT bubbled away, he realised his first mistake. ‘I said “he” when I should have said “they”,’ he says, ‘so the film’s protagonist immediately became a male. It would have been interesting to see if the AI would have shown the same bias.’ After his initial prompt, Luisi insists he did not creatively influence the project – with one caveat: he was allowed to shorten. ‘The dialogue kept having people say each other’s names: “Are you sure you want to do this, Jack?” “Yes, Sarah, I’m sure.” So I did some trimming, but I never changed the fundamentals.’

Being a creative writer, I always thought I’d be safe from AI

In the film, Jack is a successful screenwriter insistent that no machine can ever replicate the human experience he brings to his work, and is sceptical when his producer encourages him to use an AI assistant (voiced by Anna Arthur) on his next script. But he soon realises that the machine not only matches his skills, but even surpasses him in empathy and understanding of human emotions.

‘From a feminist perspective, it was maddening’

Luisi’s initial applications for funding for ‘The Last Screenwriter’ were turned down, although no one explicitly told him that the film’s use of AI was the issue. The success of ‘Bonjour Switzerland’, however, gave him the financial freedom to make the film himself, as a non-profit enterprise. He plans to release it online for free, along with all of the documentation of the screenplay process, prompts and outputs.

‘I think it’s an important film to make right now, because we’re at a crucial moment,’ he says. ‘For the first time in 127 years, there could actually be a movie that wasn’t written by a human, whether that’s good or bad. I mean, I don’t want computers to write our stories. I want to see what my fellow human beings have to say. But as an experiment, I couldn’t resist.’

It was an experiment I couldn’t resist

As a director, Luisi allowed himself more creative latitude, with one important caveat: he couldn’t change the words, for fear of invalidating the premise of the experiment. There were, however, things he could do outside of the script. For instance, in the ChatGPT version, the protagonist’s wife, Sarah (Bonnie Milnes), keeps coming in and out of the room where Jack is writing, saying something, then leaving again. ‘I kept them in the same room and gave her a laptop, as though she was a businesswoman working from home, to give her a bit more of a life outside the script ChatGPT had written for her. But I couldn’t change the dialogue.’’

Milnes, a relative newcomer who worked with Shane Meadows on last year’s ‘The Gallows Pole’, found the limitations of the machine-written role frustrating, and illustrative of a wider problem with roles for women. ‘Sarah had no character,’ she says. ‘I was like, who is this woman? “She loves her husband. She loves her son. She’s beautiful” – there was nothing to her. She was always at the kitchen sink, and everything she said was about Jack. From a feminist perspective it was maddening. But it really does show the limitations.’

Nicholas Pople, who plays Jack, admits to having had misgivings about the project, until he read the script and learned of Luisi’s intentions. ‘It’s a non-profit experiment aimed at testing the capabilities of AI, raising awareness and encouraging conversation about the use of AI within the creative industries,’ he says. ‘I thought it was an engaging approach to a very current topic.’

‘I don’t blame the cinema’

‘I’m not promoting AI,’ says Luisi, who was in full solidarity with striking Hollywood writers and stresses that ‘The Last Screenwriter’ did not take anyone’s job but his own. ‘I’m not saying this is what I think should happen with movies at all.’ Naturally, he is disappointed with the cancellation of what would have been the film’s world premiere. ‘There are always haters and commenters,’ he says, ‘and I thought the cinema shouldn’t have bowed to a few people who didn’t want it to happen. I looked at the comments, and I felt that there were as many people who would have wanted to have a discussion about it, so I think they shouldn’t have shut down the conversation.’ Pople agrees. ‘I don’t begrudge either the cinema’s decision or people who voice concerns about the project,’ he says. ‘I hope that anyone who has any interest in the subject watches the film as its aim is to encourage further debate.’

The Prince Charles is for film-interested audiences, which is why we chose it

Luisi doesn’t blame the cinema, however. ‘The Prince Charles is for film-interested audiences, which is why we chose it. The manager’s a really nice guy, and he said from the beginning: “Look, we live off our reputation, and if we’re going to send out invitations for the film and recommend it, I want to watch the film first,” and he did. But the morning after the first ad went out, they called me and said, “We’ve got lots of complaints. We can’t show it.”’

‘Our decision is rooted in our passion for the medium and listening to those who support what we do,’ said the Prince Charles in a statement on social media.

— Prince Charles Cinema (@ThePCCLondon) June 18, 2024

Alessandro Perilli, who founded research project Synthetic.Work to investigate the impact of AI on jobs, believes pulling the film was a mistake. ‘People have to understand what’s coming,’ he says. ‘They need a wake-up call. Not showing the film just keeps people in ignorance.’ Perilli says that people are unaware of how deeply AI will change the nature of jobs, both inside and outside of the creative spaces, ‘and hiding the impact from them gives those millions less time to react.’ AI, he adds, is as inevitable as Thanos. ‘Nobody will be able to stop the adoption of AI in creative fields,’ he says, noting that his research has highlighted filmmakers, Pulitzer Prize finalists, world-class artists and musicians’ adoption of AI, not just to save costs, but to see how much more creative they can be. ‘Denying the existence of the tool, by boycotting the projection of the film, is like denying upcoming artists the knowledge of new tools for creativity. You are doing a disservice to an entire generation of future artists.’

I feel like I’m not the enemy, I’m just part of the discussion

‘I believe this film provides an interesting insight into how far AI has come,’ says its star, Nicholas Pople. ‘While there are clear issues with its current capabilities, it’s important to be aware of its development going forward. AI is not disappearing; it will develop further and be used in other parts of the creative industry. My main concerns are the same as the majority of other artists. Partly, how far will people go to develop AI and implement it within the creative industry?’

Luisi’s biggest fear had been that no one would show up for the screening; it hadn’t occurred to him that it might be cancelled altogether. ‘I feel like I’m not the enemy,’ he says. ‘I’m just part of the discussion. I thought people would understand what I was trying to do. Maybe I was a bit naive.’

You can watch ‘The Last Screenwriter’ for free at the film’s website in July. For programme into on Prince Charles Cinema’s upcoming (non-AI-generated) screenings head to the cinema’s official site.

Midnight marathons, plastic spoons and shagging rabbits: an oral history of Prince Charles Cinema.

The best films of 2024 (so far).