[title]

The end is nigh! Well, maybe not nigh, exactly, but you could be forgiven for thinking so. In the wake of a pandemic, severe flash flooding and that catastrophic report by the IPCC, our own demise is more on our minds than ever. It’s got us thinking. How will London end? Why will it end? When will it end? And, most importantly, as we’re all huddled on the tube, sheltering from Armageddon, what will Time Out write about?

We got together with a couple of experts on disaster management – genuine professors of doom – to test various fantastical forecasts. The result was that I got to pose hypotheticals and they got to brutally shoot me down – or, more worryingly, confirm my suspicions.

Swallowed by an earthquake

If there’s one thing everyone knows about earthquakes in the UK, it’s that we don’t really get them. Every so often someone’s chimney falls in and it makes the national news, but it can be difficult to tell the difference between an earthquake and a passing double decker bus.

But the UK actually experiences earth tremors pretty regularly. According to the British Geological Survey, there’s an earthquake in the UK, on average, every few days. But if we’re talking ‘significant’ earthquakes (those above 4.0 magnitude), the average is less than one per year. The last (and only time on record) there was one above 6.0 on the Richter Scale in the UK was 1931, and that was in the middle of the North Sea.

Faraway earthquakes, even if they’re strong, are still unlikely to significantly affect London. Tectonic plates just don’t sit that way. Even an event similar to the famous Lisbon quake of 1755, which caused a ten-foot tsunami to hit Cornwall, is unlikely to have much effect on London at all.

‘Clearly, we’re not in the realm of Mediterranean earthquakes,’ says David Alexander, professor of risk and disaster reduction at UCL. ‘However, there are some sensitive processes that could be damaged by them – computer-related mainly – or other things connected with critical infrastructure such as the electricity distribution, network, etc. Somewhere between seven and 11 kinds of critical infrastructure – that’s water supply, food supply, banking – are absolutely dependent on electricity,’ he says.

He makes a good point. Rather than seeing an earthquake as a huge event that instantly reduces a city to rubble, maybe we should be considering the domino effect of one disrupting the electricity supply. So an earthquake, should it happen on land and relatively near London, might actually be pretty catastrophic.

Likelihood of it ending London: pretty unlikely but not entirely beyond the bounds of possibility.

Engulfed by volcanic lava

There are plenty of extinct volcanoes in the UK, from the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland to Warboys in Cambridgeshire, only 70 miles from London. But a volcano has to be active or dormant for there to be any possibility of an eruption. If the UK’s volcanoes weren’t extinct, London might be prone to lots of ash and acid rain and things like that. But they are. There’s simply no supply of (cue Doctor Evil voice) magma underneath them.

The closest active volcanoes to London are Mount Vesuvius, near Naples, and Iceland’s Öræfajökull (pronounced ‘err eye ver yer kot ull’, really quickly) on the country’s south-east coast. But London’s fate might not depend so much on where a volcano is in relation to the city, but the scale of the eruption.

The 1815 eruption of Indonesian volcano Tambora remains the largest on record, and was so enormous that historians reckon its ash partially blocked the sun and caused a global cooling period. Crops failed, food supplies were disrupted, there were riots as far away as Europe, and people died.

And climate change might make volcanic eruptions even worse. ‘Climate change is likely to lead to more instability,’ says Lee Miles, professor of crisis and disaster management at Bournemouth University Disaster Management Centre (BUDMC). ‘So we’re going to face more volcanic eruptions, which have impacts in terms of the transfer of ash and materials, which affect the quality of air, bring issues to do with water supplies and generally impact people’s way of life.’

While volcanoes are a significant danger for much of the world, they don’t pose a real threat to London’s existence. But while lava flows and explosive eruptions aren’t ever likely to directly affect London, the secondary effects are certainly worth worrying about.

Likelihood of it ending London: low. No lava-filled cracks under the Thames any time soon.

Falling prey to a pandemic

We know, we know, and probably don’t need reminding. London is a diverse, densely populated global transport hub. While that openness is part of what makes the capital so exciting and great, it also left it exposed to Covid-19.

‘The whole economy is built on an open structure and ethos,’ says Professor Miles. ‘It does make us highly vulnerable to infectious diseases.’ While the UK has had a lot of success in the roll-out of the vaccine, other areas of response to the Covid-19 pandemic have been much more hit-and-miss.

‘I think that it’s a very mixed record,’ says Miles. ‘On the one hand, I think we are better [than pre-pandemic]. On the other hand, I don’t think Londoners have learned a thing. And if it happens again we will probably face the same challenges in many areas.’ Which is a bit depressing, really. It’s probably best to move on, before things get too political.

Likelihood of it ending London: far, far greater than anyone could possibly have realised.

Obliterated by an asteroid

The killer of dinosaurs and premise of dozens (if not hundreds) of disaster films, there’s something quite intoxicating about being destroyed by a mysterious flying rock from outer space. It’s definitely one of the more cinematic ways for London to go and the reality isn’t so far-fetched. Small asteroids (anything under the 30-metre mark) usually burn up on entering the atmosphere – and plenty do so every year. We don’t have to worry about those. It’s the bigger ones that might keep you awake at night.

The impact of an asteroid that’s 140 metres in diameter could destroy a country. The impact of a 1,000-metre one might destroy civilisation itself. The one that wiped out the dinosaurs – and about 70 percent of life on earth – is thought to have been more than 10km wide. If an asteroid is big enough, it might destroy pretty much everything.

Luckily, the bigger the asteroid, the lower the chances of it hitting Earth. And, these days, apparently Nasa can divert some of them – just like that Asteroids arcade game, but instead of zapping asteroids and destroying them, it alters their path so that they don’t hit us. With what tools? Among other things, laser beams and nuclear bombs – yes, really.

‘If it’s going to happen, it’s going to happen,’ says Miles. ‘It is one of those cataclysmic events that, to some extent, it doesn’t matter where you run. The impact of a major asteroid impact on the Earth, as we know from the past, would cause extinction-level events for certain parts of the population.’

So don’t worry too much. Getting hit by an asteroid, of any size, is one of few things actually less likely than winning the lottery. Are asteroids worth losing any sleep over? ‘No,’ says Miles, ‘because what are you going to do about it?’

Likelihood of it ending London: EXTREMELY unlikely. Barely worth thinking about.

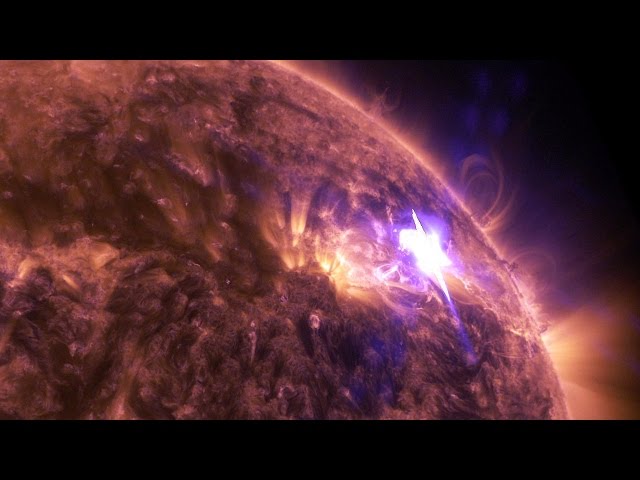

Microwaved by a solar storm

I’ll admit that I hadn’t even thought of weather events in space until speaking to Professor Alexander, a pretty telling sign that I’ve never seen such classic disaster films as ‘Solar Flare’, ‘Solar Attack’ or ‘Knowing’, and that I didn’t pay enough attention to ‘2012’. But solar storms are really serious stuff. A solar flare, a brief eruption of high-energy radiation from the sun, could knock out power and, similar to an earthquake, result in domino effects from disrupted satellites, blown transformers and paralysed medical, banking and legal systems.

As Alexander points out, the satellite disruption alone would be pretty devastating. ‘That’s not merely communications,’ he says. ‘It’s also global positioning. For example, the space weather incident that occurred in 2003 led to a vertical error of about 50 metres in positioning.’ Trust me, you do not want to be on a plane coming into Heathrow that thinks the ground is either 50 metres closer or further away than it actually is.

As for a power blackout? Society (and London) is more reliant on electricity than ever. ‘Can you imagine London having no power, no communication, no mobile phone networks for two weeks?’ says Miles. ‘There would be a kind of mental meltdown. We’d likely get 15 to 24 hours’ notice for a significant solar flare – just enough time to head to Sainsbury’s for a pitched battle over the remaining batteries.

Likelihood of it ending London: difficult to know, really.

Deluged by floodwater

If we’ve seen anything over the past few weeks, it’s that a worryingly large area of London is prone to flooding. ‘The Environment Agency suggested in a report [in January 2021] that about a third of UK flood defences are badly maintained and inadequate,’ says Professor Alexander. ‘It's worth bearing in mind that if you have a biggish surge of water, whether in a river or along the coast, you only need one tiny bit of the flood defences to fail and everything behind that then fills up with water’

But we already knew this. From London’s heavy rain a couple of weeks ago, it’s pretty clear a lot of places are vulnerable to flooding. From Walthamstow to Camberwell, plenty of London has already found itself underwater. But there’s no need to worry, you cry. We have the Thames Barrier! Wrong. ‘The Thames Barrier is part of a system of flood defences ,’ says Alexander. ‘If that breaks down then the Thames Barrier could become just a very effective barrier on an island between raging floodwaters.’

The Barrier is currently an effective tool that safeguards central London from tidal surges from the North Sea. It’s expected to work sufficiently for at least another few decades, but isn’t much help against rainfall in the capital itself. And what happens when high sea levels and tidal surges coincide with storms? Simply put, there’s too much water, and nowhere for it to go. Low-lying areas and sewage systems could all be overwhelmed.

Before the construction of the Thames Barrier, London was already prone to flooding, and climate change will make these kinds of adverse weather events more frequent. Much of us could find ourselves regularly underwater far sooner than expected.

Likelihood of it ending London: out of all these situations, the most likely. Panic!

There are obviously lots of other ways that London might end, and I haven’t even gone into most of them here. Heatwave? Nuclear accident? Global conflict? And while we can joke all day about doom and gloom, the reality of the end of London isn’t so definite. It’s almost wholesome, really. Civilisation isn’t static, Miles says. People change the way they live. And what defines London, anyway? Maybe Londoners define London, and if so, at least when we’re all stuck in tube tunnels, still avoiding looking each other in the eye, we can be comforted by the fact that we’ve got each other. The joy!

These areas of London could be underwater in a decade.

The Mayor of London speaks to Time Out about the climate crisis.